Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Culture & Civilization ›

- Renaissance to Republic ›

- France's Belle Epoque

Belle Epoque in France: Golden Age Or Gilded Illusion?

Published 03 December 2021 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

The Belle Epoque is one of my favorite periods of French history: the architecture, the bold changes, the blossoming of the arts and intellect, often known as the "Golden Age of France". But beneath the surface, was it truly as golden as it seemed? Or did it mask deeper social unrest and inequalities?

We all know the Belle Epoque in France... we see it as we walk around Paris, marveling at the exquisite curlicues of an Art Nouveau building or the light brushstrokes of an Impressionist painting.

We already love those energetic and exuberant and inventive decades that saw out the 19th century and welcomed in the 20th.

But how familiar are we with Belle Epoque France, really?

What secrets does it hold, and more to the point, was it really as great as they say?

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

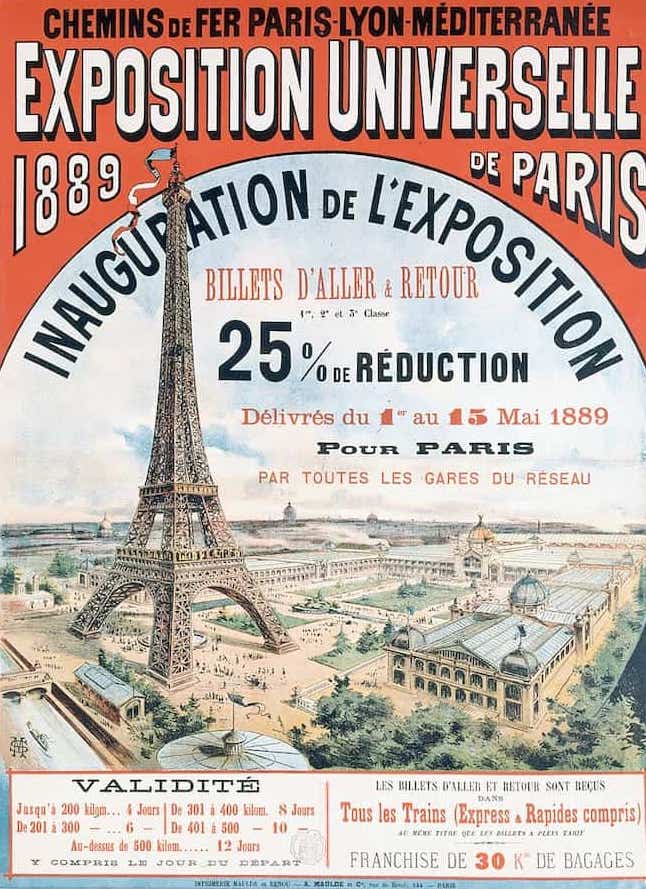

Eiffel Tower poster

Eiffel Tower posterIt’s been called a French Golden Age of sorts. Some, at a loss for words, have even called it Victorian France (well, it does piggyback on the late Victorian and Edwardian eras).

The meaning of the Belle Époque era (usually written with an accent) is, by the way, simply beautiful age. How apt.

Or is it?

What IS the Belle Époque in France?

It’s sometimes written up as “la belle epoch” but what really counts is what it stands for.

When Napoleon III (nephew of Napoleon the First) was ousted after losing the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, France was in a shambles, Paris even more so. The city was emerging from a brutal blockade so severe citizens had been forced to eat their pets to survive.

The Rue de Rivoli in Paris, damaged by fighting during the Paris Commune

The Rue de Rivoli in Paris, damaged by fighting during the Paris CommuneA short-lived revolutionary government – the Paris Commune – that took power while France and Germany were busy negotiating didn’t help matters, and soon France was faced with the ignominy of having to sign a peace treaty with Germany in that temple of French history and culture: Versailles Palace. As though losing the war wasn’t enough, France’s nose would be rubbed into its defeat.

The war also cost France Alsace and half of Lorraine, which became part of Germany, not to mention the hefty war reparations it had to pay.

France was on its knees.

When was the Belle Epoque era?

La Belle Epoque time period has been the subject of some dispute, because no one seems to be able to agree when it started. It ended with World War I, in 1914, but its starting point could be any of these:

- 1871, after the Franco-Prussian war ended and Napoleon III fell

- 1889, at the Exposition Universelle

- 1901, when the Victorian Era ended in England

What we call the Belle Epoque period had parallels around the world: in England of course, but also in Germany, under Kaisers Wilhelm I and II, in Vienna under the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, in Russia at the height of St Petersburg Czarist high society, in the United States during the Gilded Age or in Mexico during the Porfiriato.

All these periods had points in common: fortunes were made, economies flourished, societies progressed.

Often, though, it is darkest before the dawn and from this post-war devastation arose a Paris one could hardly have dreamed of.

This crumbling, beaten society would soon dive headlong into a period of political effervescence, unparalleled growth, artistic ebullience and social metamorphosis the likes of which hadn’t been seen since

La Belle Epoque Paris: a radical overhaul

I say Paris, because it was the hypercenter of the Belle Epoque. While progress and innovation did spread across France – you’ll find plenty of architectural and artistic evidence in places like Nancy or Evian or Aix-les-Bains – Paris was its heartbeat.

It was Paris, after all, which gave us such Belle Epoque beauties as the Eiffel Tower (which no one thought beautiful at the time), the Palais Garnier, the Petit and Grand Palais, those stunning metro station entrances, and the Fouquet jewellery shop, which once sat on the Rue Royale but has been reassembled right inside the Musée Carnavalet.

To many, this was the Golden Age of Paris.

A piece of the original furnishings of Fouquet Jewellers, now at the Musée Carnavalet

A piece of the original furnishings of Fouquet Jewellers, now at the Musée CarnavaletJust a few years earlier, Baron Haussmann had resculpted the face of Paris, eliminating slums, organizing the Catacombs, cutting boulevards and clearing parks along which new buildings would elegantly be placed. By the time the Belle Epoque rolled around, Paris looked much like it does today.

Belle Epoque Paris: shedding conservative art forms

We’ll start with art because this was an era of incredible experimentation, giving birth to the Impressionists, the Auguste Renoirs and Claude Monets whose masterpieces have made their owners millionnaires.

A close-up of Monet's Water Lilies at the Paris museum of the Orangerie - the ensemble has been called the Sistine Chapel of Impressionism

A close-up of Monet's Water Lilies at the Paris museum of the Orangerie - the ensemble has been called the Sistine Chapel of ImpressionismLike many things in modern life, the new artists weren’t liked at first. Traditionalist France rejected their work as ugly, unconventional, revolutionary even. But as is often the case, they not only came around, but provided an environment in which many movements were able to develop: Art Nouveau, of course, but also Cubism, and Fauvism, whose practitioners and artists painted and fashioned colours and shapes that went wild, cementing the reputation of Paris as the world’s cultural capital.

Belle époque fashion (we ARE talking about Paris, after all) was an art form of importance. Those wide open boulevards and newly planted parks were perfect for showing off the latest dresses and hats. This is where you came to see and be seen, on foot or in horse-drawn carriages, because in those days, who you were in society – and how you looked – determined much of your life. You had to keep up, because fashions changed quickly.

Everywhere they looked, Parisians saw something experimental, and the Belle Epoque was a highly visual era.

In Paris, in 1895, the Lumière Brothers projected moving pictures to a paying audience for the first time. Photography, which had come into its own, was hugely popular among the wealthy. Just as much fun were the newfangled lithography and printing techniques, which popularized those delightful Belle Époque posters which today cost a fortune to collect. These “affiches” promoted the cafés and dance halls of the Belle Époque era, the cabarets, and all those other morally questionable establishments which made Paris such a colourful place.

Paris wanted to have fun

After those difficult years of war and crushing defeat, Paris was out for a good time.

I mean, what can you say about an era that gave us the can-can, the Moulin Rouge and the bordello?

Who can forget Félix Faure, President of France from 1895-1899, more famous for his death in the arms of his mistress than for his lifetime accomplishments?

But not all entertainment in Paris was of this salacious sort. You could also enjoy the Paris Olympic Games, the Tour de France, new museums and concert halls, and the proliferation of grittier, more realistic writers like Victor Hugo and Emile Zola, whose portraits of contemporary society inform us today.

This was also when the famous Paris bouillons, which are now making a comeback, opened their doors to feed the city’s growing working class. To take a peek at one of those ‘modern’ proletarian restaurants, you step into the Bouillon Julien for an authentic Belle Epoque interior that hasn’t changed much in more than a century.

This was also the heyday of the Parisian department store and even though one or two had been built earlier, the Belle Epoque was when they were at their height.

A quick walk past the storefront of La Samaritaine (recently renovated and reopened) will give you a hint of that grandeur. Better yet, go inside. Or into the Galeries Lafayette. Or the Printemps. If you were a well-to-do Parisian of the time, that’s what you would have done.

The extraordinary cupola of the Galeries Lafayette in Paris

The extraordinary cupola of the Galeries Lafayette in ParisMany of the new entertainments were beyond the reach of the average Parisian wage-earner but here, too, times were changing, and workers were discovering the meaning of leisure, as the time and money to enjoy it slowly became more available. Science and technology helped put this within reach. Plenty of inventions saved people time, especially in transportation. Not having to walk long distances to work and being able to ride the metro or tram or a bicycle instead would revolutionize daily life.

But change wasn’t just about entertainment and beauty - it was also about everyday life.

A growing number of factories made it possible for individuals to earn money without owning land. These required more physical labour, and people – often poor farmers from France’s agricultural hinterland – moved to the cities, turning rural France into an urban society. Population grew, and so did cities. Health infrastructure improved, life expectancy increased, working conditions got better, and labour unions were born to make sure improvements weren’t temporary and were spread around to all.

So what do you do when your environment changes, your life and prospects improve, and the world around you boils over with radical new ideas?

You show it off to the world, of course.

OTHER THINGS RELATED TO THE BELLE EPOQUE IN FRANCE

It's a phrase that has taken on a life of its own and which is used to mean many things beyond that precious time leading up to World War I. Here are just a few:

- Belle Epoque film: yes, there is such a thing as the Belle Epoque movie. It is French, made in 2019, and it is NOT about this period in time but about a much more modern form of nostalgia.

- Belle Epoque book: in fact, there are many Belle Epoque books, each dealing with a different facet of the era.

- Belle Epoque fashion: this was definitely considered an era of beautiful clothes. Sleeves grew puffier, skirts became slimmer, and accessories became even more fashionable – think hats!

- Belle Epoque jewellery: this was the heyday of curves and Art Nouveau, with nature taking over as a theme. Here's a guide to the gems of the time.

- Belle Epoque architecture: complicated! A mixture of styles that include a smattering of Gothic, plenty of Art Nouveau, ceramics, and reinforced cement. Add to this, a few unexpected curves and colours.

- Belle Epoque champagne: a fresh, delicate and golden champagne created by Perriet-Jouët.

You might also like these stories!

The Expositions Universelles

The French Belle Epoque is well known for its string of universal exhibitions, but the inspiration for these events was not French at all. In fact, it came from Britain.

The 1851 Great Exhibition in London had been a long-held dream of Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband, and its guest of honour was the then Emperor of France, Napoleon III.

Having witnessed the incredible Crystal Palace and the million visitors who came, France had to have one too.

No sooner had Napoleon III returned to French soil that he immediately ordered a Universal Exposition for Paris - bigger and better than London’s, he demanded.

The first in a series of world fairs opened in 1855, a bit before the Belle Epoque, and the last would be a bit after, on the eve of World War II.

But between the first and the last of these exhibitions, three Belle Epoque expositions stand out: 1878, 1889 and 1900.

1. The 1878 Universal Exposition

This was more an event of national reconciliation after the Franco-Prussian disaster and the bloody Paris Commune, bringing everyone together with an eye on a better future. A popular attraction was the head of the Statue of Liberty, shown here before the full statue was shipped to New York.

Entrance hall of the Palais du Champ-de-Mars, at the 1878 World Fair, and its monumental clock. The Palais faced the Trocadéro, and was located on the site where the Eiffel Tower is now standing.

Entrance hall of the Palais du Champ-de-Mars, at the 1878 World Fair, and its monumental clock. The Palais faced the Trocadéro, and was located on the site where the Eiffel Tower is now standing.2. The 1889 Universal Exposition

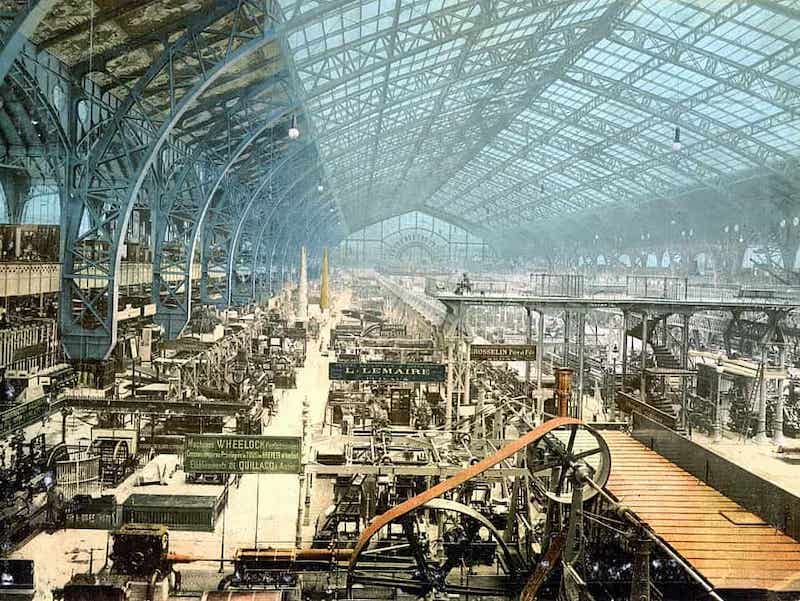

This marked the 100th anniversary of the French Revolution and the taking of the Bastille. Most of all, it celebrated industry, at a time when France was getting back on its feet and needed to be pushed out of recession (there’s nothing like a world’s fair to bring in money, tourists and pride!)

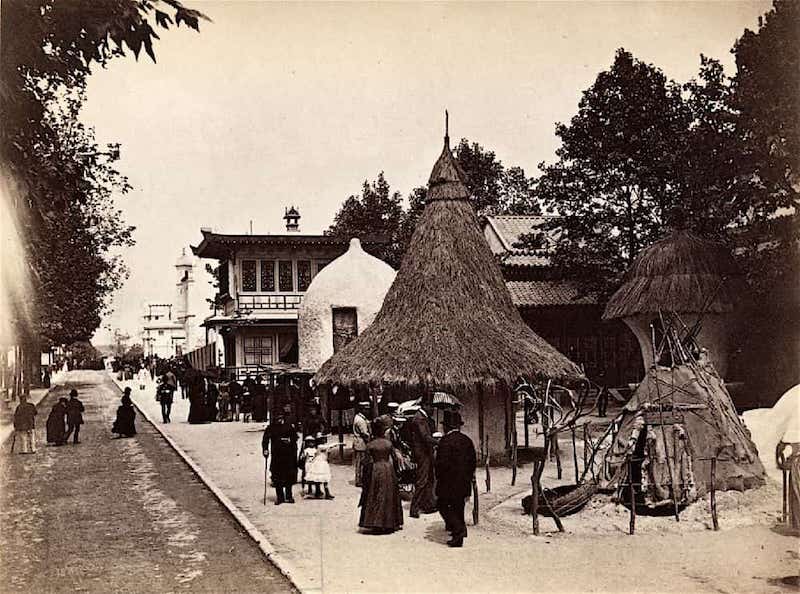

The Galerie des Machines showcased the industrial savvy of the time, and such seemingly impossible feats as the Eiffel Tower saw the day here, at the time the tallest structure in the world. Spread out at its feet were 44 “villages” representing various foreign lands and colonies.

The Central African village, one of the 44 represented at the exhibition and laid out at the foot of the Eiffel Tower

The Central African village, one of the 44 represented at the exhibition and laid out at the foot of the Eiffel Tower The Argentina Pavillion, which won the prize of best pavillion

The Argentina Pavillion, which won the prize of best pavillion Inside the Galerie des Machines, reminder of the industrial revolution, courtesy Library of Congress

Inside the Galerie des Machines, reminder of the industrial revolution, courtesy Library of Congress3. The 1900 Universal Exposition

The 1900 Paris Exposition was designed to herald the arrival of the 20th century and celebrate the past century’s achievements – of which, as we have seen, there were plenty.

More than 50 million people came, and major venues were built throughout Paris just for the occasion. We can thank the exposition for the Pont Alexandre III, the Petit and Grand Palais and the Gare (now Musée) d’Orsay, to name a few. Of course all the technical innovations would have to be shown off as well, such as the great Paris ferris wheel, escalators and moving sidewalks, or the new “talkies”. Napoleon III would have been proud.

Moving walkway at 1900 Paris World's Fair. The two left platforms moved at different speeds, while the right one stayed stationary. Courtesy Brown University

Moving walkway at 1900 Paris World's Fair. The two left platforms moved at different speeds, while the right one stayed stationary. Courtesy Brown University The Pont Alexandre III, built 1896-1900 in time for the 1900 Paris World's Fair. The Grand Palais is on the left and the Petit Palais on the right. Courtesy Brown University

The Pont Alexandre III, built 1896-1900 in time for the 1900 Paris World's Fair. The Grand Palais is on the left and the Petit Palais on the right. Courtesy Brown University The main entrance of the 1900 Exposition in Paris with the triumph gate by René Biné. Courtesy Library of Congress

The main entrance of the 1900 Exposition in Paris with the triumph gate by René Biné. Courtesy Library of CongressThe dark underside of La Belle Epoque era

However glorious the inventions and the modern buzz and the expansion, all was not perfect during the Belle Epoque. The advances in health and working conditions were all the more phenomenal for their distant starting point: huge inequalities and devastating poverty.

Social inequality was the rule

Many French people were poor, especially in the countryside, where agricultural crises would push them to the cities. Here, they would crowd in insalubrious shantytowns, living a life of insecurity and precariousness, with no heating, insufficient food and little clean drinking water (aqueducts had been destroyed by the Franco Prussian war).

The lack of drinking water in Paris would, by the way, be partly remedied by an English philanthropist, Sir Richard Wallace, who built fountains across Paris to provide clean water to those who couldn’t afford to pay for it. You can still see them dotted around Paris.

As workers thronged to the factories, many of their co-workers would be children – up to 20% of the workforce. Brave souls tried to reform this and succeeded somewhat; laws were passed, but not implemented, as few families could afford to live without the extra income from their children’s work.

Women’s rights were few and far between in what was a highly patriarchal society, one in which men, mostly white men, had power of life and death over women (it would take until 1944 for women to get the legal right vote in France).

Should you happen to come across it, Paris Police 1900 is a contemporary television series that will make you gnash your teeth with its discriminatory and antisemitic dialogue, all perfectly attuned to the mores of the time.

Discrimination and racism were common and acceptable.

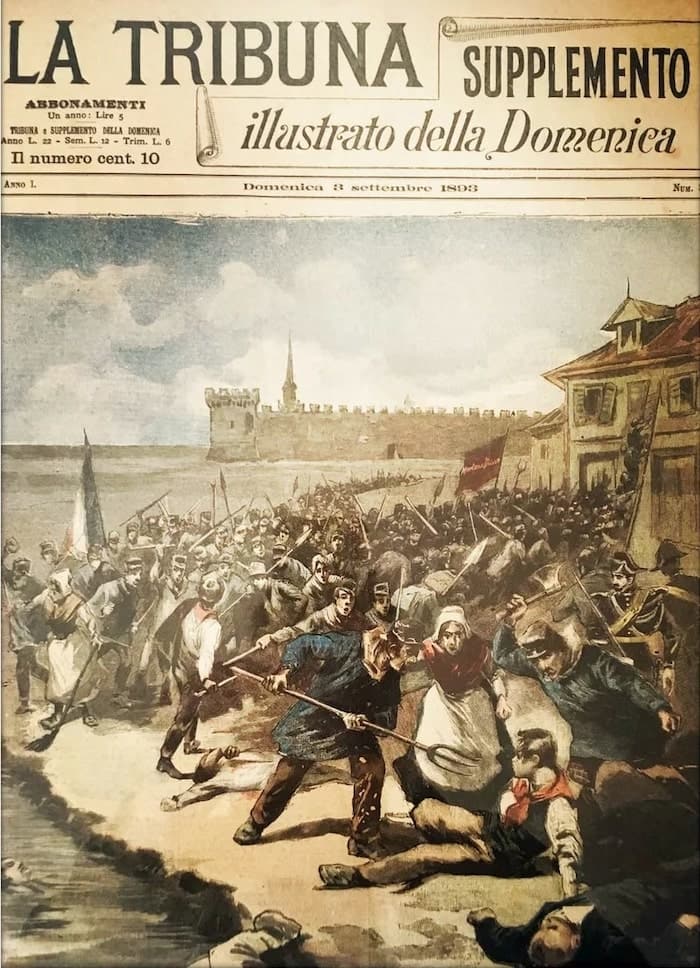

In one infamous incident in the southern French town of Aigues-Mortes, in 1893, a group of Italian seasonal salt workers was murdered during social tensions after rumours that they had assaulted French workers. This led to a pogrom-like massacre in which Italian workers were hunted through the streets, cornered, and dozens were killed. Initially, the local Prefect pardoned the killers but had to resign after an international outcry.

Newspaper cover of the Aigues-Mortes massacre

Newspaper cover of the Aigues-Mortes massacreBut perhaps the most representative event of the time stands out so starkly it is still spoken of today is the Dreyfus Affair, a hysterical mass-media lynching of a man accused of disrespecting France.

L’affaire Dreyfus

Like a civil war, it pitted brother against brother and caused rifts among friends that never healed.

In 1894, Alfred Dreyfus, a French army officer, was wrongly accused of passing secret documents to the Germans. It turned out not to be true – a certain Esterhazy had been guilty but that didn’t stop authorities from finding Dreyfus guilty, sentencing him, and jailing him not once, but twice. Dreyfus was Jewish.

It would take 12 years to exonerate him but his rehabilitation divided France. Passions were fuelled by anti-Jewish media. The Catholic La Croix prided itself for being the “most anti-Jewish newspaper of France”, a phrase printed right across its banner. It is something for which the paper (which still exists) has extensively apologized and tried to set right.

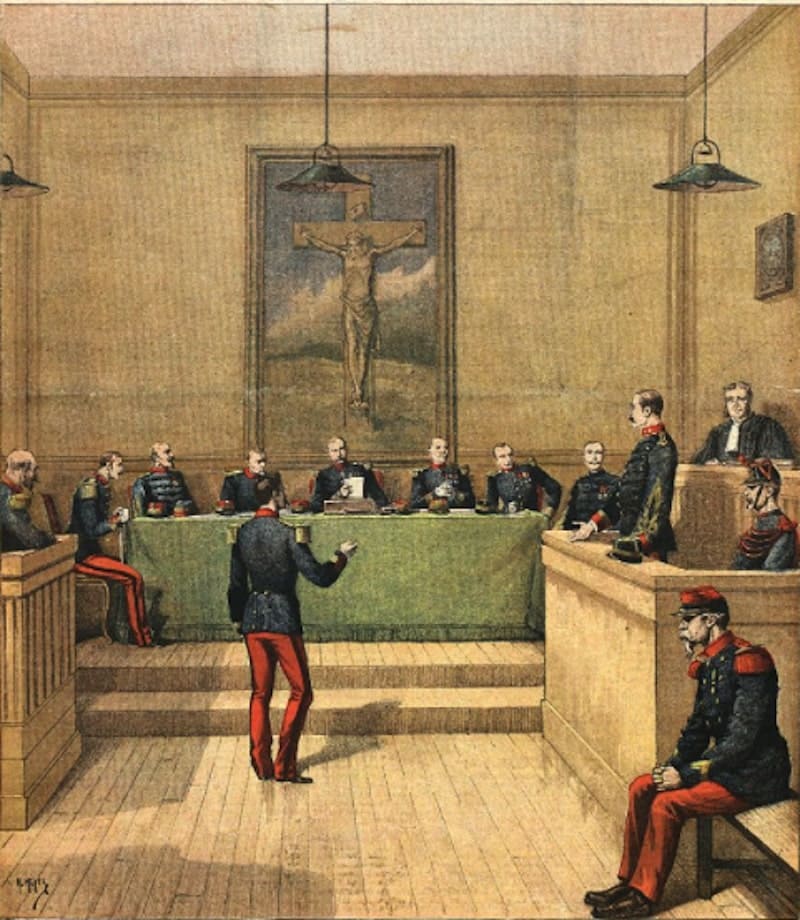

Captain Dreyfus being court-martialed, from Le Petit Journal of 23 December 1894

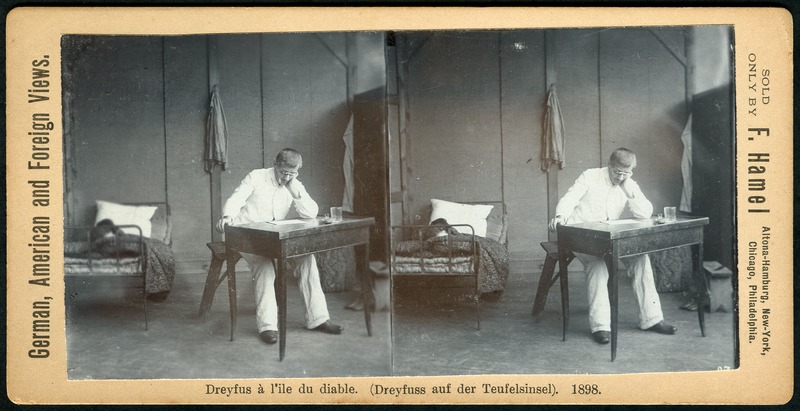

Captain Dreyfus being court-martialed, from Le Petit Journal of 23 December 1894 Dreyfus imprisoned on Devil's Island

Dreyfus imprisoned on Devil's IslandThis was a time of political experimentation. Remember that the Second Empire had just ended with Napoleon III, and the monarchy had been extinguished not that long before, in 1830. Then we had the revolutionary Paris Commune, so when it came to the republic, it was anything but solid.

Most power was still concentrated in the hands of the military, and the clergy held major sway over social life, including education. What the Dreyfus affair succeeded in doing was to diminish these powers: the military was seen as a reactionary power-grabbing institution, while the clergy was discredited for its discriminatory stances. Ultimately this led to a separation of church and state that continues to this day.

The consolidation of France

For most of its history, France was a collection of states, with regional loyalties stronger than national ones. We were Burgundians or Bretons, not French. That took time.

As the French Revolution rolled around, only a quarter of France spoke French. The rest spoke regional tongues, often better than French, which was used for official matters but not day-to-day life. It took the Revolution to make it the language of education, and the Belle Epoque to make primary school free and compulsory, catapulting French into every household, with parents often learning from their children.

This gave France a stronger sense of identity, and of course made it easier to galvanize voters when the time came to head for the polls. It also meant that for the first time, workers could leave the depth of their provinces and go find work elsewhere, which they did, in droves.

The Scramble for Africa and a nation’s identity

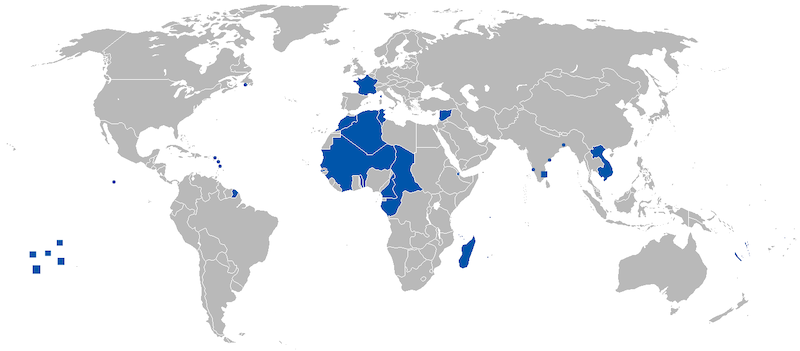

Beyond the "pretty pavilions" put up by foreign countries and overseas colonies during the Universal Exhibitions, this was the era of the dreadful scramble for Africa, when Europeans marched in, conquered, divided and ultimately gave themselves a pat on the back for ruling “their” bits of Africa. By the end of the era, 90% of Africa would be under European rule, a large swathe of it “belonging” to France.

France's colonies at the time of the Belle Epoque by Shid0x02 CC BY-SA 3.0

France's colonies at the time of the Belle Epoque by Shid0x02 CC BY-SA 3.0From the French point of view, these foreign ventures were a success, expanding as they did France’s halo overseas. Like the inventions and advances of the time, colonial empires would be shown off during France’s exhibitions.

And then it came to a crashing halt

Some people contend the Belle Epoque was only “belle” in hindsight, that it was the calm before the storm.

They’re probably right. If you were living during this time, you would not have called it La Belle Epoque. That only happened once it ended.

La Belle Époque meaning: the origins of the name

No one can pinpoint who coined the term Belle Epoque or when the words were used for the first time. But there are plenty of theories:

- The most popular story is that the horrors of WWI prompted people to look back at a time of peace and prosperity. As they cowered in the trenches, perhaps memories of music and laughter was what kept them going.

- Other sources say the name was coined much earlier, towards the end of the 19th century.

- And then there are those who place the name far later. According to one historian, it was first coined in 1940 on a radio programme about the 1900s on Radio-Paris about the 15 years that preceded World War I - a possible reaction and comparison with the awful 1930s.

The consensus seems to hover around 1919, if the majority of historians are to be believed, so named after World War I, in yearning for an era long gone.

The Belle Epoque provided France with a 40+year uninterrupted stint of peace, but human nature being what it is, that couldn’t last.

By 1914, Paris was frenetic, awash with the energy of progress and living life as though it might soon come to an end - little did they know.

When World War I erupted, its destruction made it easy to look back with nostalgia on the past and call it the Belle Epoque.

Many arts had flourished, turning drab everyday living into bursts of unimaginable colour. The working classes and lower bourgeoisie began enjoying life, however modestly, much improved by the many technological and scientific discoveries of the age: vaccines and hygiene for health, telephones for communication, cinema for entertainment, electric street lights for security, the new methods of transportation - there’s no question many aspects of life became easier. The old religious and military orders lost power and the face of politics became solidly republican. Even foreign policy was upended.

Walk around Paris today and you’ll see its legacy everywhere: the metro entrances and Wallace fountains, the Pont Alexandre III and the Palais Garnier, the major department stores, all of which metamorphosed Paris.

Stand by one of these and use your imagination. If you eliminate the cars and change the clothes, can you see the Belle Epoque? You should, because certainly in some parts of central Paris, very little will have changed.

So was the Belle Epoque truly “belle”?

This was a time of inventions, of new kinds of transportation and advances in health and innovative entertainment, a time of enormous artistic and intellectual creativity and innovation, and a time of social upheaval and change.

Elegant balls of the 19th century portrayed here in Une Soirée Élégante by Victor-Gabriel Gilbert

Elegant balls of the 19th century portrayed here in Une Soirée Élégante by Victor-Gabriel GilbertSo physically, visually, yes, the Belle Epoque was sublimely belle!

From the point of view of technology, of course it was.

Even politically and socially, it was an incredible time – many lives improved, although when we talk about the Belle Epoque, we should remember that some enjoyed it and benefited from it far more than others.

But yes, the name does seem apt.

Belle Epoque FAQ

How to pronounce Belle Epoque

Belle-ay-POCK

When was Belle Epoque?

There is no firm date, but it is widely accepted to have started sometime after the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, ending in 1914 just before World War I.

What is the belle epoque meaning?

The meaning of belle epoque is, quite simply, beautiful era.

Who were the top Belle Epoque painters?

Belle Epoque art – which covers a multitude of styles – is represented by such well-known artists as Paul Gauguin, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Henri Matisse, Auguste Rodin and many more. This was also the heyday of the French Art Nouveau movement known as the Ecole de Nancy.

What is Belle Epoque style?

Flamboyant, curvy, natural... and so much more. On the one hand, it exemplified progress and social change, and on the other, it harked back to the past in nostalgia.