Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Ze French ›

- La Gastronomie ›

- French Pastry Desserts

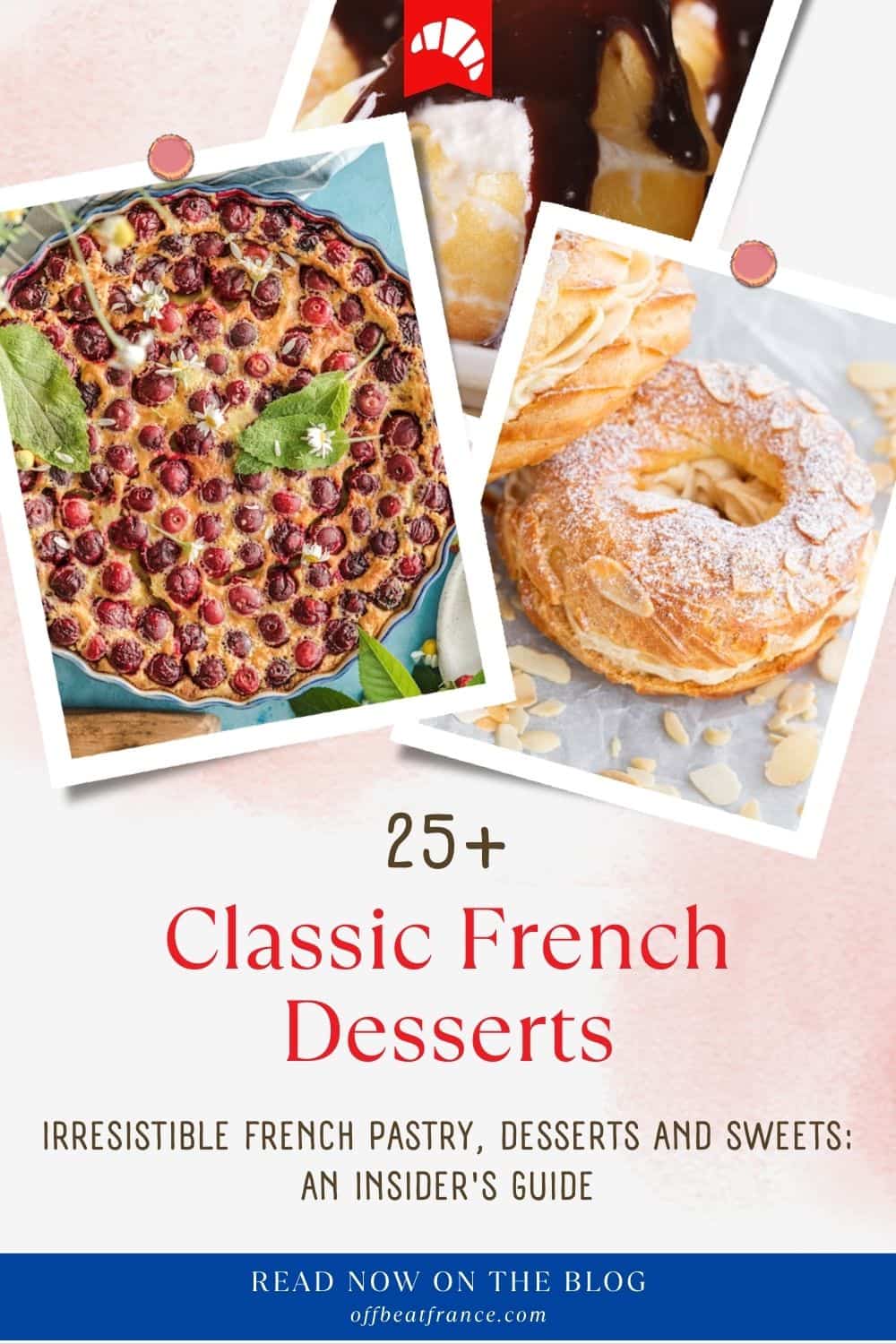

25+ Irresistible French Pastry, Desserts And Sweets: An Insider's Guide

Published 30 August 2021 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

If there's one thing I find irresistible across France, it's walking by a bakery and feasting on the croissants and French pastry desserts that dance across the display counters. We do have the most wonderful pastries!

One of the most "sinful" things you can possibly do when visiting France is stopping by a café or salon de thé (tea room) in mid-afternoon and having a snuffle around the French pastry desserts counter.

Chances are you won't come away empty handed.

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

All the most famous French pastry desserts

There's little doubt: France knows how to do desserts.

Not too sweet, not too tart, not too sickening.

Just right. So right, in fact, that where you might usually eat one, in France you'll want two. Maybe three.

Many of us (especially if we are French) are convinced that France is a temple of gastronomic gratification, with delicious dishes that are more akin to experience than just a meal (although France does have its share of weird foods too).

A meal here can be sublime, with French pastry desserts being the final crown.

A traditional French meal (the typical French breakfast excluded) will usually involve an entrée, which is a starter, followed by a plat principal (a fish or meat dish, or, in an upmarket or very traditional restaurant, one of each), a fromage (cheese) and, finally, dessert (or should I say French pudding for my British friends).

It's this final item that concerns us here.

Below I've listed France's favorite desserts, in alphabetical order of French dessert names, or my biases will come through!

These are the ones we eat more or less regularly (thought not in excess), the ones you'll find most often in your local French patisserie. I've also added a few regional specialties which are equally common, but mostly in their respective regions.

Finally, I suggest you have a bite to eat before settling down to read this piece, or you might be rudely interrupted by the sound of your stomach gurgling.

Baba au Rhum

Baba au Rhum, a French gateau dipped in rhum, and in this case, embellished with fruit and jam

Baba au Rhum, a French gateau dipped in rhum, and in this case, embellished with fruit and jamYou've probably seen this in your local pastry shop but passed it over, because it's plain and relatively unadorned, unlike the brightly coloured pastries probably sitting right next to it.

It's an unpretentious little thing, a simple cake soaked in rhum, with the usual addition of a bit of whipped cream.

While many French desserts have foreign origins, this one may sound tropical but it is resolutely French, from Lorraine, in fact, near Nancy.

And there's a story behind it.

It would seem that during the first half of the 18th century, the former king of Poland, Stanislas Leszczynski – he was living in Lorraine at the time – liked to eat a certain cake that reminded him of the Polish babka (sounds like baba?). But they were a bit hard and he was a bit old and his teeth were a bit worn, so his chef Nicolas Stohrer had a brilliant idea: soaking the cakes with sweet wine.

Some years later, a Parisian pastry chef – a descendant of the Polish king's chef –came up with a proper recipe, and replaced the wine with rhum, and so the Baba au Rhum was born, because an old ex-king had wobbly teeth.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Canelés

One of those French pastry desserts you can never get enough of...

One of those French pastry desserts you can never get enough of...I first tasted these on my maiden visit to Bordeaux, which claims this delicacy as its own. At the time, you couldn't find them easily elsewhere, although these days France has woken up to the delicious taste and texture of this little cake. It has a spongy texture, with the thinnest of thin caramel coatings.

It seems to have emerged from cakes once baked by nuns in a Bordeaux convent sometime in the 16th century. Its name would then have been canelat or canelet, because it was wrapped in cane before frying. Apparently the nuns recovered flour left in the holds of ships and used it to bake the canelés

In another legend, the name might come from breads baked by so-called canauliers during the 17th century.

It seems it was once spelled with two "N"s, but one N was dropped with the creation in the 1980s of the Brotherhood of the Canelé, one of France's many food- and drink-related brotherhoods. These days, it can be spelled either way. It's still the same cake.

Such a simple recipe for such a delicious little thing — flour, milk, sugar, vanilla and rhum. And that simplicity often yields the most delicious results.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Café Gourmand

Authentic French pastries, supported by coffee, if you're looking for petite French desserts

Authentic French pastries, supported by coffee, if you're looking for petite French dessertsAll this is very well and good, but what if there are so many choices you simply cannot decide? When that menu of French pastries arrives and ten minutes later you're still reading?

Enter the café gourmand, for which there really isn't a translation: the closest I can come is connoisseur coffee... or assorted mini French pastries.

Basically it's a coffee, which you have at the end of your meal (coffee is never with your meal in France), accompanied by 3-6 mini-pastries, often samples of the larger desserts that might be on the menu. It is a great way to taste a bit of everything without being overwhelmed... In a good restaurant, the pastries will be as high in quality as the actual desserts. In a lesser establishment, you might be getting something slightly under-par, so I'd save this one for your better outings.

I do admit I find this hard to resist when I see it on a menu...

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Clafoutis

The clafoutis, a French cherry dessert

The clafoutis, a French cherry dessertMmmm, memories of childhood. Because it is so easy to make, one of the most simple French desserts, this is one of the first recipes our mothers teach us.

I still remember my surprise at seeing the cherries peeking out of the custard like dark little half-moons.

The French cherry clafoutis seems to have become popular in the 19th century and comes from the Limousin region. It's a simple flan (a lot of people would dispute it, preferring to call it a cake), with cherries added, although sometimes it might be made with other fruits, like plums or blackberries (in which case it is called a flaugnarde). It's a simple mixture of eggs and milk and sugar. Whip it up, add cherries, fill a pie shell. Doesn't get much easier.

And if you're not scared to swallow one or break a tooth, you may leave the pits in.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Crème Brûlée

Crème brûleé belongs on every French dessert list - even as part of mini desserts

Crème brûleé belongs on every French dessert list - even as part of mini dessertsOh so loved, this simple dessert, basically egg yolks and milk, dates back to at least the late 1600s and somehow hits sublime notes, with its unbelievably creamy and smooth insides and an impossibly thin yet crunchy crust. It's a bit rich, so I prefer to eat it with meals that don't include cheese.

Some say crema catalana, or Catalonian cream, predated crème brûlée and may have even been its inspiration. A later cookbook in 1740 mentioned something called English Cream, and a certain "burnt cream" seems to have made its formal appearance at Cambridge University in 1879, with its coat of arms branded on the sugar crust.

French crême brûlée really hit its stride in the 1980s, when it became one of the most popular French desserts, popping up on every menu. It's still a mainstay...

But is it really French? Since we don't know, we can simply claim it.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Crème Caramel

Creme caramel is definitely one of the classic French desserts

Creme caramel is definitely one of the classic French dessertsIt's hard to believe that the flan, or custard, actually originated in Rome, not surprising since the ingredients are eggs and cream, and the Romans had both chickens and cows.

Not only did it see the day in Rome but it survived through the centuries, became sweet (earlier versions were not) and eventually made its way to the New World, making it probably the favourite dessert of Spanish-speaking countries.

Today, it remains widely and wildly popular throughout Europe, and you'll find it on many French dessert menus.

This French creme caramel simply isn't... French. But we treat it as such.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Crêpes Suzette

Crêpes Suzette is a classic of French restaurant desserts

Crêpes Suzette is a classic of French restaurant dessertsThis is an old-fashioned dessert, the kind my grandmother used to love, but you will still find it on menus, especially in hoity-toity restaurants, since it involves actually setting fire to a dish to flambé it, one of the more fancy French desserts.

But its origins are disputed.

The most common goes back to 1896 in Monte-Carlo. This story credits Auguste Escoffier, who was head chef of the Grand Hôtel at the time, with their invention. He would have created them in honour of the Prince of Wales, future King Edward VII. The prince may have been accompanied by a certain Suzette and when Escoffier offered to name the dessert after him, he demurred, claiming it was so good he was undeserving and that it should be named after Suzette instead.

Other origins are claimed: Henri Charpentier, Rockefeller's chef and a student of Escoffier; by Escoffier himself (at the Savoy in London in 1890); or by a Paris restaurant owner, but for the same Suzette.

We may never know but the recipe itself remains relatively unchanged: crêpes, covered in a sauce (sugar, butter, orange or tangerine juice and lemon zest), splashed with alcohol (usually Grand Marnier or triple sec), and set on fire at the table.

The alcohol, by the way, might have been an accident... while preparing the crêpes, the inventor (or the person serving them) spilled alcohol over them and, unable to fix the mess, simply flambéd them. It was a great success!

But, please note: this means Crêpes Suzette are not French, but from Monaco...

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Éclairs

An eclair is one of those French summer desserts, ideal for a snack, or to munch on a picnic bench

An eclair is one of those French summer desserts, ideal for a snack, or to munch on a picnic benchWho doesn't indulge in the occasional éclair?

It's a simple little dessert, a choux pastry − the same one used for profiteroles − filled with a custard (usually chocolate, coffee or vanilla) and glazed with icing of the same flavour. And one you're bound to find in almost any French pastry shop.

These days they're modernising the éclair and you'll find a zillion fillings, from whipped cream to pistachio to fruit salad with lemon glaze. I'm a traditionalist and nothing beats a good coffee éclair...

It seems the éclair entered the world of French sweets in Lyon in 1850, but it wasn't called an éclair but a duchess: it had the same shape and filling but was rolled in crushed almonds. Still sounds delicious.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Fondant or Moelleux au Chocolat

These names of French desserts are sometimes interchangeable, and often confusing...

These names of French desserts are sometimes interchangeable, and often confusing...I'll be honest with you here: I often can't tell these two apart. They're both made of chocolate, and they both have a soft interior. Yet there's no basis for confusion because the two are significantly different.

The moelleux always has a runny center, surrounded by a cake. To make the inside run, a frozen ganache or chocolate is inserted into the cake and melts when heated.

The fondant, on the other hand, doesn't have a liquid heart but melts in your mouth because of its creamy texture. It usually doesn't contain any or much flour, certainly less than the moelleux. And it's certainly among France's favourite desserts.

And then there's the mi-cuit... it's enough to drive you around the bend. They have the same ingredients, and all that changes is the amount of baking.

In the end, it doesn't matter, does it? If you love chocolate, at least try one of these, or better yet, try all three.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Fraisier

A fraisier, one of the classic French strawberry desserts

A fraisier, one of the classic French strawberry dessertsNo two fraisiers look alike, I've found. A fraisier usually involves vanilla whipped cream, cake, marzipan (sometimes) and strawberries (always.).

Like strawberry shortcake, the fraisier seems an almost natural home for the comforting strawberry.

It's such an obvious dessert that there's little chance of ever unpacking its origins. There are traces of it in Escoffier's Culinary Guide, and subsequent pastries have incorporated bits and pieces of it.

After all, if you had strawberries and wanted to make a pastry, wouldn't it likely end up looking a bit like a fraisier?

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Gâteau Basque

French Basque cake, for your next visit to Southwestern France

French Basque cake, for your next visit to Southwestern FranceAs its name implies, this is a regional delight you'll find in France's Basque country, that southwestern tip that borders Spain.

Its name, Basque cake, may be slightly unprepossessing, but when you look at the original − etxeko bixkotxa − you'll be glad its creator found another name for it.

Yes, this is a dessert whose origins can actually be traced: it is a family recipe elaborated in the early 19th century by Marianne Hirigoyen, pastry chef at Cambo-les-Bains' one and only pastry shop (Combo-les-Bains is a small thermal town in the Basque interior).

It sped around by word of mouth and soon became so popular it even came to the attention of Napoleon III (nephew of the first) and his wife, Empress Eugénie.

It is usually filled will custard or black cherries (typical of the Basque country), although apricot, nut and even chocolate fillings have been spotted − a rich mixture of crunchy and moist, and yes, sweet.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Glaces

Ice cream, believe it or not, is typical of any French desserts list

Ice cream, believe it or not, is typical of any French desserts listSimple.

Ice cream. Much loved in France.

How loved is it? We consume 5.5 liters of ice cream per person per year. In total, that's about 360 million liters of ice cream yearly. More staggeringly put − France eats 11 liters of ice cream per second.

As for flavour, traditional French desserts are, well, hopelessly traditional: vanilla and chocolate.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

You might also like these stories!

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Île Flottante

The Île Flottante is a favourite of children and adults alike

The Île Flottante is a favourite of children and adults alikeThis is the Île Flottante I just sampled in a Lyon restaurant.

You know how many desserts can vary from place to place? That rarely happens with Île Flottante: it tastes remarkably the same, wherever you go: a airy meringue, floating on a bed of vanilla-infused custard and covered with a light sprinkling of slivered almonds and a ribbon of caramel. It's the perfect "light" dessert after a heavy meal; it is rich, but somehow light.

As with many French desserts, this one (in its vastly different original version) was invented by Auguste Escoffier, a pillar of French gastronomy. The original recipe isn't clear. In one, a biscuit soaked in alcohol and covered in jam, raisins and almonds and covered in whipped cream. In another, apples might have been involved.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Kouign Amann

A Kouign Amann, hard to resist Skimel, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

A Kouign Amann, hard to resist Skimel, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia CommonsThis particular regional delicacy is from Brittany and dates back to the mid-19th century. It even has an inventor: Yves-René Scordia, a baker, naturally.

It's not too difficult to describe: take a croissant, add more butter, add sugar, and bake it as a cake, cut off pieces as you need them. At times it's also baked individually. It doesn't matter, right? But if you're a butter fiend...

The name, by the way, comes from cake (kouign) and butter (amann).

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Macarons

Macarons, crunchy and creamy, light and rich

Macarons, crunchy and creamy, light and richThis little stuffed wafer, a royal member of the fraternity of French sweets, has taken the country by storm, even though it wasn't born here. As is the case with a number of sweet delicacies, this one originated in the Middle East, making its way to Europe as Europeans began to travel (perhaps via the Christian Crusaders of the Middle Ages) and, eventually, into France through Catherine de Medici (wife of Henri II of France, and mother of three later kings), whose Florentine savvy brought so many different foods into France.

And from there the humble macaron took off, was adapted, morphed and evolved. It seems to have started life as a single wafer, doubling up in Paris around 1830 and held together by a filling − catapulted by Ladurée in Paris, and now one of the most famous French desserts ever.

But there were plenty of regional versions, for example the Basque macaron, which persists to this day in southwestern France.

It's more popular flavours are the standard ones: raspberry, hazelnut, pistachio, vanilla... but innovation is never far when it comes to macarons and you'll find them ranging from the crazy to the inventive − liquorice, foie gras, sesame, saffron...

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Marrons Glacés

These glazed chestnuts are French Christmas desserts, usually appearing on shop shelves around November

These glazed chestnuts are French Christmas desserts, usually appearing on shop shelves around NovemberAs autumn rolls around and Christmas begins to make its first sounds, a crinkly sound can be heard in sweet shops and chocolate stores.

That sound is the unwrapping of marrons glacés, which usually come tucked into a square of golden foil.

The little gem in question is a simple chestnut coated in sugar. Who knew such a little thing could provide such a taste explosion?

It may be simple, but it's not easy and takes several days to make. The chestnuts are soaked, peeled, protected in a net (against breakage), boiled, soaked in sugar syrup for 48 hours or more, drying for a week, triage (to eliminate broken chestnuts or undersized ones), iced with glaze, and finally, baked briefly to give them their sheen. They are then individually wrapped and packaged in special foil, in a wooden box for upmarket products, in cardboard boxes or plastic sachets. They're even sold individually, so that afficionados like myself can buy one or two when desire strikes.

They should be stored at room temperature to retain their taste but, frankly, they rarely last long enough to dry out.

Beware, though − spend the extra and buy the best quality, because a poorly prepared marron glacé can be gritty, dry, and simply doesn't do this justice.

That said, such a popular sweet may not even be French! The glazed chestnut is claimed by both France (in the time of Louis XIV) and by Italy, but whatever its origins, it is a ubiquitous part of the Christmas holidays.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Mille-Feuille

Here it is, the perfect mille-feuille, sometimes also known as Napoleon French pastry. Zantastik, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Here it is, the perfect mille-feuille, sometimes also known as Napoleon French pastry. Zantastik, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia CommonsThere's something deeply comforting about a mille-feuille. Perhaps it's because it is a traditional French dessert, one we equate with childhood Sundays or a special treat. All I know is I have been eating them all my life and still, today, my senses go on immediate alert when a mille-feuille is in sight.

Traces of the original pastry can be found in an early 17th-century recipe, although today's iteration is made with vanilla and the original contained alcohol.

But then it gets murky. The most common story has the delectable mille-feuille emerging in 1867 in a Parisian pastry shop and is touted as a 'specialty'. Word-of-mouth did its job and soon, people were lining up in the streets to buy this aromatic combination of puff pastry, custard, vanilla, and icing.

But there are other, rarer spottings of these in pastry shops as early as under Napoleon Bonaparte, earlier in the 19th century.

Its name? Mille-feuille means one thousand sheets, as in sheets of pastry. There aren't that many, but there are quite a few. These days it has been 'improved' with the addition of fruits, or chocolate, or other items. In fact, many earlier versions seemed to include jam. My local pastry shop has taken to using jam, but as far as I'm concerned, you shouldn't mess with perfection.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Mont-Blanc

This is one of those French dessert foods that you like more each time you eat it

This is one of those French dessert foods that you like more each time you eat itOf the many pastries on this page, this one may be more of an acquired taste than the instant sweet explosion we've come to expect. It's popular in several countries where chestnuts are common, like Italy and Switzerland – countries which are also neighbours of Europe's highest mountain.

And while it's called Mont-Blanc in France, in neighbouring Switzerland it's called 'vermicelli'. You'll see why in a moment.

The basic ingredients are simple: chestnut purée, a heart of meringue (not always!) and whipped cream (in some cases you might find cake or pie crust at the bottom but, unnecessary).

The purée is run through a large sieve and comes out in strings, spaghetti-like, at the other end (hence its Swiss name).

It seems this dessert was imagined in Italy towards the end of the 15th century before making it to France a couple of decades later. But that's not the only possibility. Another is that it was created by the renowned Parisian patisserie Angelina. Either way, Angelina made it famous. It suffered a dip in popularity for a few decades but has been reinvented as the quintessential winter warm-up delight.

Mont-Blanc, by the way, also happens to be the name of a Caribbean coconut-based cake...

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Mousse au Chocolat

This wonderfully innovative mousse was packaged into a caviar tin by the former chef of the Belooga Restaurant in Villefranche-sur-Saône, north of Lyon

This wonderfully innovative mousse was packaged into a caviar tin by the former chef of the Belooga Restaurant in Villefranche-sur-Saône, north of LyonAhhh, who hasn't had a meltdown while eating an impossibly rich chocolate mousse? And would it surprise you to know the chocolate mousse had been invented by a Swiss chef?

Charles Fazi was Louis XVI's chef and was already being mentioned around 1755, althought the recipe itself − chocolate, cream, egg yolks and sugar − emerged more than 60 years later in André Viard's Cuisinier Royal, a venerated recipe book.

From then on, the mousse will become increasingly popular as one of the best French desserts, and one to be made at home. Apparently Toulouse-Lautrec may have even contributed to the recipe!

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Opéra

The Opéra, definitely high up on the France dessert list

The Opéra, definitely high up on the France dessert listI have no idea why I love this little pastry so much − to me it is the queen of French pastry desserts. Perhaps it is because of the proper proportions of its various components... cream, icing, cake, everything perfectly layered. Or maybe because it has one of those French pastry names that soars and makes you dream...

The Opera may have been first advertised in a magazine in 1899 but really joined the mainstream around 1955, when the pastry chefs at Dalloyau − Cyriaque Gavillon and his wife Andrée − named it after the Opéra Garnier.

It wasn't easy sailing, however. Gaston Lenôtre, founder of the Lenôtre culinary empire, claimed the dessert (or a remarkably similar one) as his in 1960. Finally, the newspaper Le Monde decided the original did indeed belong to Dalloyau...

When it was created it was considered exceedingly modern, because of its geometric and minimalist lines, and because of its ingredients − the elimination of alcohol (which was part of the original) and a reduction in sugar. The idea behind was novel as well: each layer would be visible, and would all be tasted in a single bit.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Paris-Brest

The Paris-Brest, rich and crunchy

The Paris-Brest, rich and crunchyThis delicious puff pastry filled with praline mousse and sprinkled with icing sugar and slivered almonds, was actually designed to look like a bicycle tire. It also happened to be made with a secret ingredient (rather than butter).

In 1891, the Paris-Brest cycling race was inaugurated. Along the route, in the town of Maisons-Lafitte, a pastry chef by the name of Louis Durand decided to celebrate the race with, what else, a pastry.

He fashioned it in the shape of a bicycle tire (although some would prefer to interpret the shape as a victor's crown). No matter. What counts is the taste...

People now come from all over France to taste the original Paris-Brest at the Patisserie Durand, which continues to thrive under the watchful eye of the original inventor's great-grandson.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Pâte d'Amande

Marzipan figurines, French traditional desserts or served alongside coffee

Marzipan figurines, French traditional desserts or served alongside coffeeYou probably know this as marzipan and in France, it comes in two varieties: almond paste, which usually contains egg whites, and marzipan, which does not. To add to the confusion, both are called marzipan here!

No matter... Many pastry shops or confiseries (candy shops) will have rows of little marzipan figurines. You can eat them as snacks (I get through a bag quickly), or they may appear as mignardises, sweets in France (or petits fours) that are sometimes served alongside your coffee. They can be shaped like animals, or fruits, or furniture, or anything under the sun. Marzipan is also used in a variety of recipes, as icing, or as cake decorations. It's wonderfully versatile and has innumerable uses.

As for marzipan itself, its origins lie in Ancient Persia, and like many other sweets, it made its way westward towards Italy, Germany and Spain.

In France, it is first heard of along St James's Way, possibly brought back from Compostella by returning pilgrims.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Pâtes de Fruits

I always order mine from Cruzilles (cruzilles.fr) in the Auvergne...

I always order mine from Cruzilles (cruzilles.fr) in the Auvergne...Ah, the childhood memories of dipping my hand into the proverbial cookie jar, usually a plate with a bell on top to keep out the summer flies...

Simple little squares of fruit paste covered in sugar – traditionally these are local fruits like apples or apricots, but the selection has expanded to more modern or exotic fruits like lichee or pomelo or even combinations like pineapple and basil.

The pâtes seem to date back to the 10th century but would garner some renown only five centuries later, in the Auvergne region – in fact, they were then known as pâtes d'Auvergne... and this was the region that produced them. Later, Provence would take over and today, that's where most are made (but the Auvergne still makes some of the best).

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Profiteroles

Profiteroles, definitely one of the most famous desserts in France

Profiteroles, definitely one of the most famous desserts in FranceSurely this French chocolate pastry will not only thro your diet out the window but will lock the window afterwards to make sure it can't get back in.

I simply have to see the word 'profiteroles' on a menu and my focus instantly zaps to dessert. One of the best desserts in France.

And one of the simplest: a plain choux pastry is usually filled with crème patissière, or custard, and covered in chocolate syrup or sauce. That's the basic recipe. Sometimes, the choux will be filled with vanilla ice cream (my favourite) or whipped cream, and topped with a craquelin, a crunchy caramel wafer.

The addition of ice cream, by the way, may have come from Louisiana, where profiteroles were exported more than 200 years ago. But given the hot climate, custard would curdle and so was replaced with the cooler and more stable ice cream.

The main ingredient, the choux pastry, is believed to have emerged from the kitchens of Henry II's Florentine wife, Catherine de Medici, in the mid-16th century

Initially, though, the choux pastry wasn't a dessert at all. The choux pastry was stuffed with savoury goodies, like pheasant pieces or truffles or chopped mushrooms. Sometimes, they were even used in soup.

The first reference we have to its sugary version comes to us from a great French chef and culinary writer, Antonin Carême, in his 1828 book, Le Cuisinier Royal Parisien.

In Paris, try the Profiterole Chérie at 17 Rue Debelleyme, a few minutes from the Picasso Museum, for profiteroles of every possible flavour.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Religieuse

The Religieuse is one of the many French chocolate desserts

The Religieuse is one of the many French chocolate dessertsThis is quite similar to the éclair, a puff pastry with a filling, but there the similarity ends. Like the éclair, the filling is crème patissière and there is icing. You get not one, but two choux, held together by some piping.

This is yet another invention we can lay at the feet of Catherine de Medici's chef during the sweeping culinary transformations she brought along with her from Florence.

It's one of those French desserts that are shrouded in mystery: Why is it called a religieuse? It seems its shape is reminiscent of a bishop's mitre... although that does seem a bit farfetched.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Tarte au Citron Meringuée

This little meringue tart is an exquisite French lemon dessert

This little meringue tart is an exquisite French lemon dessertThis is your individual portion French lemon meringue pie, which isn't quite like the one you may be familiar with – although in truth they share a story of origin. The North American version has a jelly-like lemon center and a light and creamy meringue, both layers quite thick. The French version is more compact, with a slightly more textured lemon cream and a stiffer meringue. If done properly, it would also be less sweet.

The modest tarte au citron has quite a history, and each bit of this dessert seems to come from somewhere else: the lemon cream has its roots among the Quakers of England, often eaten by sailors to boost their intake of Vitamin C and help prevent scurvy. The early lemon pie seems to have made its way to Switzerland, where an Italien chef invented the meringue in 1720.

But it would take nearly a century for the lemon pie and the meringue to come together. In 1806 in Philadelphia, an American pastry chef, Elizabeth Goodwell, would have pioneered its creation.

According to the newspaper Le Monde, one of the best pies in France is to be found at Les pÂtissiers, 29 Rue du Marechal Foch, 67190 Mutzig.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Tarte aux Myrtilles

This blueberry pie photo is courtesy of Arnaud 25, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This blueberry pie photo is courtesy of Arnaud 25, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia CommonsThis one is simple: blueberry pie.

It is an alpine dish, and blueberries abound in the mountains, so where everyday supplies are harder to come by, people use what's at hand – blueberries and a pie crust (ingredients aren't hard to find), with a blueberry glaze.

It may have different regional names, but asking for a tarte aux myrtilles (tart-o-meer-TEE) will deliver this to your table.

Originally a winter dish, you can pretty much find it all year-round when blueberries are in season. I haven't been able to find out much more about it, but it stands to reason: you have fruit on your doorstep, you pick it, and you find a way to eat it. It might just be as old as the invention of fire.

✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱ ✱

Tarte Tatin

The Tarte Tatin is a French apple pie, baked with the crust on top

The Tarte Tatin is a French apple pie, baked with the crust on topThis is a sort of French upside down apple cake, or pie, with the crust baked on top and unctuous, caramel-slathered apples below. Eaten warm, you can add ice cream, and some modern versions have it surrounded by custard cream (far too sweet as far as I'm concerned, not one of those inventions that improves on the original) or fresh cream (a bit less criminal, in my opinion). It is one of the most classical French desserts...

Legend has it that the Tatin sisters, who owned a restaurant in central France, invented it accidentally. Having forgotten the crust, one of the sisters decided to add it over the apples in the oven. Another tale has one of the sisters dropping the pie while taking it out of the oven, picking it up, and serving it upside down. Hmmm.

In truth, while during the Belle Epoque, towards the end of the 19th century, the sisters did promote this pie and give it their name, the Tarte Tatin has in fact been around for centuries, a recipe handed down from mother to daughter. The Tatin sisters made it popular. There's another rumour though – that the chef at the famous Parisian restaurant Maxim's might have snooped around their kitchens to purloin the recipe (this tale seems somewhat suspicious).

For a fabulous Tarte Tatin, head for Berthillon at 29-31 rue Saint-Louis en l'île, perfect for when you're all museum-ed out. (Berthillon also makes fabulous ice cream.)

And now, having perused this list of French pastries, you'll be oh so knowledgeable once you finally make it to that patisserie!

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!