Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Culture & Civilization ›

- Renaissance to Republic ›

- Château de Cirey

Voltaire in Love: The Improbable Power Couple of the Chateau de Cirey

Published 27 December 2022 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

When I arrived at the Chateau de Cirey, I was plunged into an era I knew little about. I would uncover facets I never suspected about the life of Voltaire. Especially his love life and his everyday existence.

It was the Enlightenment in France, a time of erudition (in certain classes) and grand ideas and social exploration, a time that so fascinates me that as soon as I heard about this chateau and its links to Voltaire, I had to know more.

It was the "Age of Reason", and came with new ideas of freedom and tolerance, upending traditional blind obedience to authority (church and monarch) and opening avenues to change.

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

Life in the Enlightenment

Voltaire's adoption of these "newfangled" ideas got him into no end of trouble, leading to exile and imprisonment. He was constantly looking over his shoulder and it was during one of these episodes that a conversation with a certain Émilie du Châtelet, a brilliant scientist, led to an affair, and a place of refuge where he could escape the strictures of Paris.

The fact that Voltaire and Émilie had an affair was not particularly unusual for the times – plenty of aristocrats had affairs as long as appearances were kept up – but this affair was in the public eye, the couple making no effort to hide it.

Add to that the Marquise du Châtelet herself: she was an intellectual and a scholar, at a time when women were supposed to be merely adornments.

But first, who, exactly, was Émilie du Châtelet?

A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF ÉMILIE DU CHÂTELET

- Her full name was Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, marquise du Châtelet.

- She was born in 1706 into the lower nobility and her father held a position at the court of Louis XIV.

- She was educated in a way few women were: like her brothers. She was taught physical sports, a multitude of foreign languages, and, eventually, mathematics and science, in which she excelled. She would also love dance and music, along with jewels and the latest fashions.

- Her parents arranged a marriage with the Marquis Florent-Claude du Chastellet-Lomont, who became governor of Semur-en-Auxois in Burgundy, some distance to the south.

- After leaving her husband behind, with his full agreement, she had a series of lovers before (more or less) settling down with Voltaire, with whom she would live for 15 years.

- Her most notable work would be the translation from Latin to French of Isaac Newton's Principia Matematica and the commentary she wrote with it, both still in use today. She would publish many other scientific works.

- Hers was no superficial erudition: she would just as easily criticize the English philosopher John Locke as she would influence the writings of the German philosopher Immanuel Kant or develop concepts of energy conservation.

Voltaire and Émilie: Power couple of the Enlightenment

Being 12 years her senior, Voltaire may well have met Émilie when she was younger, in one of the literary salons her father used to hold.

By 1733, when they formally met at some Parisian high-society do, they would certainly have been aware of one another. They had friends in common, and Emilie had attended some of Voltaire's plays. They fell almost instantly in love, an attraction as intellectual as it was emotional and one of the bigger love stories of the era.

"Everything in her is noble, her attitude, her tastes, her writing style, the way she speaks, her politeness..." He would come to describe her as a "great man whose only fault was being a woman".

—Voltaire

Contrary to custom, they didn't keep their liaison hidden and went out together, in love, under the eyes of the "tout-Paris", shocking some people and captivating others.

Soon, though, Voltaire would have one of the many encounters with authority for which he was famous. The publication of his pro-English Lettres Philosophiques was seen as critical of the French regime and he wisely fled to the countryside. Émilie offered him refuge in her husband's château at Cirey-sur-Blaise, in the Haute-Marne.

The Lettres Philosophiques got Voltaire into trouble. In it, he admires the English (not a good look in those days in France), in a series of "open letters" praising freedoms ranging from religion to politics to business. France reacted poorly and issued a warrant for his arrest. BUY THE BOOK ON AMAZON

He had long wanted a calm country home where he could write, so he accepted, and soon they were doing the unthinkable: living as lovers under the same roof.

He had planned to stay three months, until things in Paris calmed down.

But the chateau was in poor shape and needed repairs, and Voltaire was accustomed to a certain level of luxury. So he set about making improvements, including by adding a wing and an entire floor.

He loaned Émilie's husband the necessary funds for the renovation, and subsidized her lifestyle. The marquis, for his part, mostly stayed away, supportive of the arrangement. His had, after all, been a marriage of convenience, and he accepted – and admired – Émilie's intellectual prowess, giving her the freedom to express her potential.

A QUICK BIOGRAPHY OF VOLTAIRE

- His real name was François-Marie Arouet, born in Paris in 1694 and Jesuit-educated. He changed his own name to Voltaire in 1718, as part of a reinvention effort.

- He became a satirical writer with a wicked pen, often on the wrong side of the authorities.

- He alternated between freedom, exile and prison: the more enlightened he was, the more vocal he became, irritating the authorities and often being punished for it.

- He was a prolific writer and philosopher, penning over 2000 books. He had anticlerical views and believed in fundamental freedoms of religion and expression, not much to the liking of the monarchy and catholic church. He promoted education, attacked abuses of power, and believed that reason, not dogma, would improve the world. Many of his ideas would underlie the future French Revolution.

- He would live at the Château de Cirey with Émilie du Châtelet for 15 years, in a relationship of mutual support, he of her science, she of his writing.

- When Emilie died in 1749, Voltaire traveled abroad, ending up near Geneva in Ferney, returning to Paris only for a few months before dying there in 1778.

Chateau Cirey: idyllic backdrop for an illicit affair

Arriving at the chateau's sweeping drive up from the village of Cirey-sur-Blaise, it's easy to understand how Voltaire would have been smitten, Émilie or not.

The château at Cirey-sur-Blaise as we know it today was built on the remains of a feudal castle, and references to a castle here can be found as far back as the 11th century.

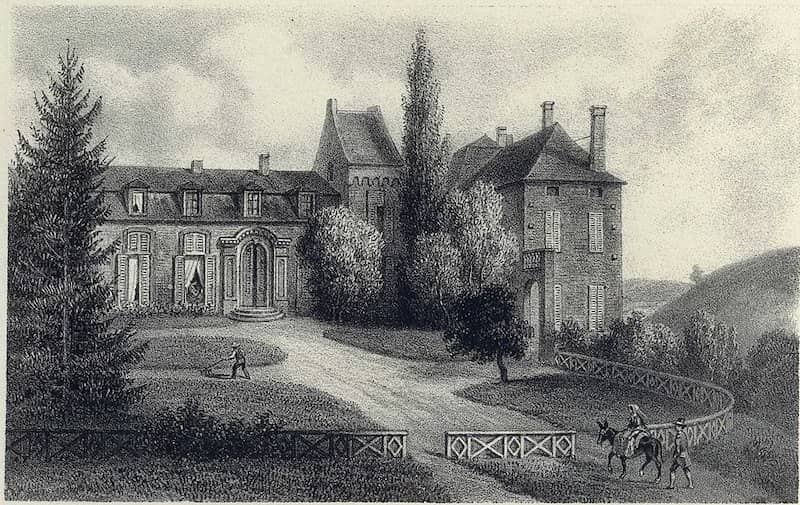

How the Chateau de Cirey would have appeared to Voltaire

How the Chateau de Cirey would have appeared to Voltaire The Chateau de Cirey as it stands today. (Photo by Ph.Lemoine.Coll.MDT52)

The Chateau de Cirey as it stands today. (Photo by Ph.Lemoine.Coll.MDT52) The entrance courtyard of the Chateau de Cirey

The entrance courtyard of the Chateau de Cirey Stonework on the façade of the Chateau de Cirey. (Photo by Aetius520, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Stonework on the façade of the Chateau de Cirey. (Photo by Aetius520, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)Gazing at the calm little River Blaise, meandering towards the mighty Marne, I could easily imagine Voltaire, gently guiding his rowboat, casting about for inspiration.

A FASHIONABLE COUPLE?

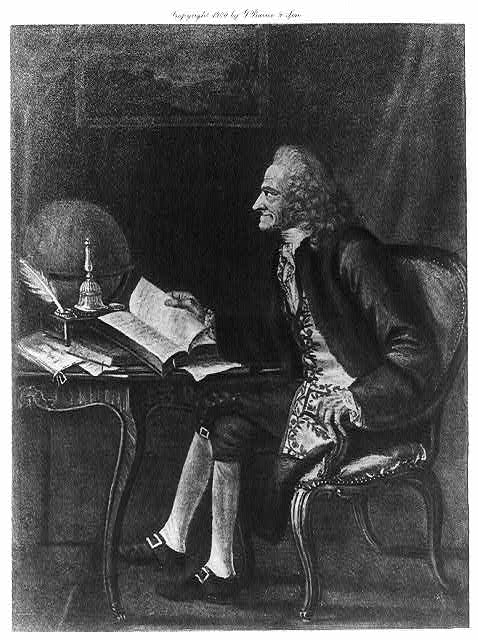

Not quite. Voltaire may have been ahead of his time but he could not be called particularly fashionable.

He wore long strings of pearls, acutely out of style in the 18th century. He also wore full wigs, at a time when men were seen with partial wigs and a pony tail.

Émilie, on the other hand, was highly conscious of the fashions of the day and went out of her way to be well turned out, jewels and all. (Below is Voltaire at several periods of his life, from young (left) to older.)

By the way, some of the photos of the château's interior will only show partial views. Photos aren't allowed inside but the owner kindly allowed me to take a few to publish here.

After going through a "vestibule", or entrance room, the first sight you'll see upon entering the castle is the massive marble stairway which hasn't changed since Voltaire and Émile made their way up and down.

As is often the case in houses of this size, the walls are full of ancient tapestries, as not even the best of chimneys can warm through walls of solid stone and soaring ceilings.

Many of the older tapestries have now gone, but those that remain on walls and furniture depict scenes popular during the 17th century, like the delightful fables of Jean de la Fontaine, which we were all forced to memorize as children.

Daily life at the Chateau de Cirey

The lives of Voltaire and Émilie were predictable and organized.

Each morning, Votaire would rise at 5 am and work for five hours, usually with Émilie. Anyone visiting would have to stay in their room until 10 am so that he wouldn't be disturbed. At ten, he would ring a bell and guests would emerge, ready for an intellectual discussion of whatever project was keeping them busy.

One of Émilie's contemporaries, Madame de Graffigny, was an assiduous letter writer, as were many educated women in those days, one of the few outlets for their talents and creativity. We rely on her many descriptions to get a sense of what Cirey would have looked like in its heyday, since much of the decor was destroyed during the French Revolution and has had to be reconstituted.

Portrait of Emilie du Chatelet at work

Portrait of Emilie du Chatelet at workÉmilie's bedroom, too, is reconstituted from Mme de Graffigny's letters. The bed is a little short – I certainly wouldn't fit and I'm average in height – but there's a reason for that.

At the time, people had strong fears of dying and sitting up partly compensated for these fears, as an upright position was believed to help ward off death.

Nor did people sleep in the same bed, unless they were poor and unable to afford their own sleeping quarters, hence the narrowness of the bed.

And finally, women a few centuries ago were distinctly shorter and slimmer than we are today.

Émilie's bedroom: beds - and people - were much smaller then

Émilie's bedroom: beds - and people - were much smaller then Émilie's desk: scientists back then had few instruments with which to work; mostly they relied on their intellect

Émilie's desk: scientists back then had few instruments with which to work; mostly they relied on their intellectThe kitchens in chateaux such as Cirey tended to be large, in proportion with the number of people who had to be fed.

Guests would not be served individually and would help themselves. Since tables were long, the same dish would be duplicated several times, strategically placed within reach of small groups along the table.

Of course plenty of service rooms have survived, including the pantry, the kitchen, and the washing room – along with a prized collection of original irons.

The fireplace, once used for cooking

The fireplace, once used for cooking While linen was changed often, up to several times a meal, whitening only took place a few times a year. Help may have been plentiful and cheap, but making cloth white was too time-consuming, even for a large staff

While linen was changed often, up to several times a meal, whitening only took place a few times a year. Help may have been plentiful and cheap, but making cloth white was too time-consuming, even for a large staffA private chapel was added to the castle during the 19th century, and while it was mostly for the castle's inhabitants, villagers also came for mass every week. These days, the chapel opens for the village on special occasions, like engagements or baptisms.

Part of the chapel decor of the Chateau de Cirey

Part of the chapel decor of the Chateau de CireyThe end of an idyll

Voltaire and Émilie were very much in love for the first few years, but they both had roving eyes and their relationship would soon move to a higher plane.

They may have had their amorous ups and downs, but their intellectual communion was steady. They even published together, Émilie gaining a recognition for her scientific work unheard of for a woman at the time.

Together they built a library of more than 20,000 books, the equivalent of a university library in the 18th century. They sought "truths", and wanted to leave their mark on the world. Theirs was a true partnership, and in the original folios of their works, you can see his annotations on her writings and hers on his.

In 1748 and 1749, the couple visited the Château de Lunéville, home of Polish ex-king Stanislas and father-in-law of Louis XV (the famous square in Nancy is named after him). Émilie would fall in love with a young poet, Saint-Lambert, and become pregnant.

The story ends badly: he didn't seem to reciprocate her love, and would never recognize their daughter. Emilie would die a few days after the birth, and the daughter two years later, unloved and uncared for.

Towards the end, Émilie sensed she had little time. Pregnancy was no easy process in those days and like most women, she would have been acutely aware of the risks. She doubled her efforts to translate Newton's work, adding her personal – and analytical – commentary. She died within days of completing a work that, unlike her, would live on. Even in the 20th century, her studies would be used by scientists the likes of Einstein as a basis for their own.

As for Voltaire, he would bounce around Europe for a bit until ending up first in Geneva and then next door, over the border, in Ferney, where he would spend most of the rest of his life.

Émilie's son (with her husband) and his wife would eventually inherit the castle, but during the French Revolution, both were guillotined and the castle ransacked, with everything ripped away, from the woodwork to the art to furniture and even door locks. After the revolution, Émilie's niece had to buy her chateau back from the government, an empty shell.

Redecoration and restoration would take place during the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th, which is why everything we see today is a reproduction, not the original.

With one exception.

Voltaire's private theater

Hidden away in the attic is a small unprepossessing room which Voltaire used as his own private theater, a dream come true for a playwright.

Here, several evenings a week, his latest plays would be enacted, with actors drawn from the château's guests and often including Voltaire and Émilie.

The theater is one of the only pieces of Cirey which survived the revolutionary ransacking. There was little of value here, a few seats and a backdrop or two, so it wasn't worth destroying. Its very modesty is what saved it and today it is one of the oldest private theaters in France.

Voltaire's private theater

Voltaire's private theaterThe Chateau de Cirey today

The château was never completed. An illustration held in the Maison des Lumières in the walled town of Langres shows the château in its final, aspirational version.

The present owner, Adélaïde Pringalle, inherited the château. Her great-great-grandfather, an industrialist from eastern France, bought the property and handed it down the generations. It now carries two distinct labels: that of national historical monument, and Maison des Illustres, the label France uses to denote a house in which an illustrious person has lived – in this case, the listing refers to Émilie du Châtelet, NOT Voltaire.

After spending much of their careers away from Cirey, Adélaïde and her husband Thierry have now made it their family home, and it is open to the public for guided tours at regular times. It's absolutely worth the visit, because of its history of Voltaire, certainly, because of its link to one of France's most brilliant women, and because it is an organic home, where people live, and not just a museum piece.

Getting to Cirey is best done by car. It's an easy drive through bucolic countryside. If you need to rent a car, make sure you compare prices first.

You can also reach the chateau by taking the train to Bar Sur Aube (2 hours from Paris) and then a taxi (you'll need a friend who speaks French to call and reserve so it can meet you at the train).

If you're in this region and you have a car, you must take the time to visit Charles de Gaulle's former home and memorial, only 15 minutes away.

Essential France travel resources

BOOK YOUR ACCOMMODATIONS

I use booking.com: for their huge inventory and for their easy cancellation policies

FLIGHT DELAYED OR CANCELED?

AirHelp can get you compensation (it works, I've used it)

DO YOU NEED A SIM CARD FOR FRANCE?

Here's the one I use when I travel abroad

PROTECT YOUR BELONGINGS

Keep pickpockets away with an anti-theft purse or an infinity scarf - and your identity with a VPN (I'm using Nord VPN)

TRAVEL INSURANCE

I recommend Visitors' Coverage or SafetyWing. for health away from home

GETTING FROM A TO B

I use Discovercars to rent cars and either Omio or RailEurope for train tickets

TO READ ABOUT FRANCE

Here's my long list of books about France

AND DON'T FORGET YOUR GUIDEBOOKS!

➽ Lonely Planet's Best Road Trips France

➽ DK Witness Road Trips France

➽ Any of the Green Guides series

➽ And, while you're at it, why not a map of France?

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!

|

|