Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Destinations ›

- Southern France ›

- Chateau d'If

The Fascinating "True" Story Of The Legendary Chateau D'if

Published 26 February 2024 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

The Chateau d’If, in the south of France off the port of Marseille, was made famous by the Count of Monte Cristo novel, partly set here. I visited recently and share the legendary chateau’s intriguing history, along with practical visiting details.

Approaching this forbidding fortress from the sea – there is no other way to approach it – you can almost relive the arrival of Edmond Dantès, the hero of the beloved work of fiction Count of Monte Cristo, who was jailed here after an unjust accusation.

As his boat neared the formidable towers, his anguish was such that he considered throwing himself overboard.

“Dantes rose and looked forward, when he saw rise within a hundred yards of him the black and frowning rock on which stands the Chateau d’If. This gloomy fortress, which has for more than three hundred years furnished food for so many wild legends, seemed to Dantes like a scaffold to a malefactor.”

—French Writer Alexandre Dumas

Even with the bright sunshine that habitually bathes the harbor of Marseille, the Chateau d’If looks forbidding, its massive stone walls anchored by watchtowers and dungeons, all sitting on a bed of rock that defies escape, especially for an unequipped, terrified prisoner.

One could almost trudge up the steps next to an imaginary Dantès, sharing his torment as he is pushed through an entrance into a courtyard he will only glimpse for a short while – his fate is to be solitary, with little more than a dish and some straw.

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

The Chateau d’If lives in our imagination, whether we are French or not.

Many people have read the Count of Monte Cristo, or seen one of the films dealing with the story of love, captivity and revenge. And if you haven’t, you’ll want to after visiting here.

Even if you have only one day in Marseille, you can still take the trip across...

A fortress born from fear

The fortress was built between 1529 and 1531 on the orders of the king of France, Francis I, or François I: he wanted to protect the strategic city of Marseille from sea invasions, protect the royal flotilla based at Marseille, and, frankly, keep an eye on Marseille herself, only recently incorporated into France.

Steps leading to into the fortress, Marseille's own Alcatraz, the formidable prison off the coast of San Francisco

Steps leading to into the fortress, Marseille's own Alcatraz, the formidable prison off the coast of San Francisco The relatively airy courtyard isn't anything like the windowless dungeons poor prisoners were confined to

The relatively airy courtyard isn't anything like the windowless dungeons poor prisoners were confined to The cell of Edmond Dantes, where living conditions were not the same as those of wealthy prisoners

The cell of Edmond Dantes, where living conditions were not the same as those of wealthy prisonersUnder the Ancien Regime, France’s political system before the Revolution, exiling prisoners to fortresses, often built on islands, was the norm.

That symbolism of isolation continued through the two exiles of Napoleon Bonaparte. To keep him away, he too was sent to island prisons, first to Elba, and finally to St Helena.

As for Dantès, familiar with the bay of Marseille, he know just how tantalizingly close he was to the city, close enough to swim, had he been able to reach the sea.

An ideal prison, the coast of Marseille in the distance, and Notre-Dame de la Garde on the hill

An ideal prison, the coast of Marseille in the distance, and Notre-Dame de la Garde on the hillThe Chateau d'If was perfectly placed for defence, with Marseille on one side and the open Mediterranean, one of the busiest sea routes, on the other.

Its potential use as a prison escaped no one and since it hadn’t been called upon for defence, it became a jail, mostly for political prisoners. At one point, after Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes which had given everyone religious freedom, some 3500 Huguenots (French Protestants) were held here in transit before being chained to “les galères”, or the galleys, where they would go to die.

The fort would be evaluated by Vauban, Louis XIV’s genial military architect, and found wanting, so he made a few modifications – lower ramparts, a guardhouse, and a military barracks that carries his name.

As you take a tour of the island you'll come upon the Vauban barracks, pictured on the right

As you take a tour of the island you'll come upon the Vauban barracks, pictured on the rightThe fictional Dantès remains the Chateau d’If’s most renowned prisoner – but there were other famous inmates.

It was also home to Jean-Baptiste Chataud, the captain of the Grand-Saint-Antoine, the ship that brought with it the bubonic plague that killed over 100,000 people in Marseille and Provence in 1720.

Despite deaths on his ship, he had pushed on towards Marseille, where wealthy businessmen anxiously awaited the arrival of goods from the Orient for resale at a major fair. Everyone had been guilty of greed and corruption, but one man took the fall.

Another notorious prisoner was the Count of Mirabeau, one of the faces of the French Revolution. Like other wealthier patrons, he lived in an upmarket cell with a bed rather than straw, a chimney, decent food and all the modern conveniences (not many at the time, though).

Many left their names behind and the walls are filled with their graffiti – along with the marks of more modern-day visitors who may have taken advantage of an uncrowded day to leave their mark.

You can see the faint inscriptions on the plaque on the left and the graffiti on walls to the right

You can see the faint inscriptions on the plaque on the left and the graffiti on walls to the rightThe Château d’If, immortalized by literature

So many books, plays, radio series and movies have been based on the novel – too many to count.

And it's easy to understand why. As I re-read the tale for the umpteenth time, it is every bit as compelling as the first, with Dantès's fabled escape keeping me on the edge of my seat.

The Chateau d'If is now a historical monument, far from its earlier role as a state prison

The Chateau d'If is now a historical monument, far from its earlier role as a state prisonMonte Cristo - a true story?

Believe it or not, the Count of Monte Cristo may have been based on a true story.

A certain Pierre Picaud, a shoemaker from Nîmes, was about to marry when an evil love rival turned him into the authorities as a traitor (which was a lie, of course). The shoemaker is arrested and languishes in a notorious prison for seven years, where he befriends a wealthy Milanese abbot who wills him his fortune. Then, just like the novel, the shoemaker sets about seeking his revenge.

Proving this as true has been a challenge, however, and most literary experts suspect Pierre Picaud was none other than the invention of a crime writer at the time. No matter – this is one of those places where myth and reality intertwine.

Why the Château d'If?

Alexandre Dumas hadn’t always planned to set the earlier part of his tale at the Chateau d’If. But having heard his father speak of it, he dropped by during a trip to Marseille and was so taken by its forbidding aspect that he decided to incorporate it into his novel.

As for the name, it came to him on another trip, this time to Tuscany, when he sailed past a rocky outcrop near Elba: the small island of Monte Cristo, where medieval monks had apparently slain a dragon and amassed a treasure, whose rumor spread among pirates and which also fueled Dumas’s imagination. And so are legends perpetrated.

Where life imitates art

It is quite easy to understand how, having read the story, one might want to rush across the bay of Marseille to see the Château d'If in person. The novel was published in 1844 and by 1850, readers were already clambering into boats to cross to the rocky island and walk in the footsteps of Edmond Dantès and the Abbé Faria, the story’s two heroes.

To make things even more “realistic”, a tunnel was actually dug between cells, a bit like life imitating art. Today, the chateau is a historic monument and things must be left as they are.

Early tourists turn the chateau into a tourist attraction

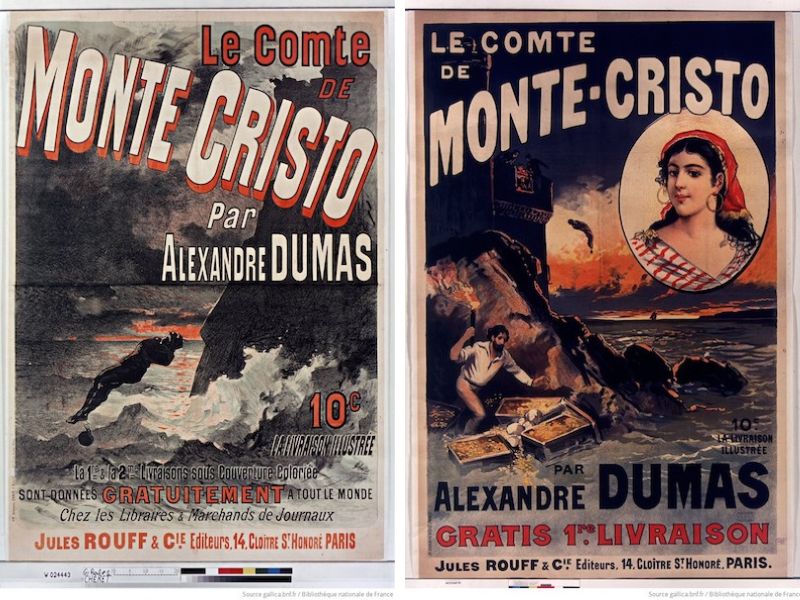

Early tourists turn the chateau into a tourist attraction Advertising posters for the serial novel. Source: Source gallica.bnf.fr / BnF

Advertising posters for the serial novel. Source: Source gallica.bnf.fr / BnFNot everyone is convinced

Adding to the mystery that tends to shroud places like this is the firm belief some people have about its historical existence.

Asking a few visitors at random during my visit, I did get a few raised eyebrows, but one young couple enthusiastically confirmed they had read the book, believed this part of it to be true, and now wanted to see the “real thing”. This is the power of good literature.

If you haven’t read it yet, head for the library or order your own copy before you visit. (There’s a leatherbound version that would make a lovely Christmas or birthday gift for someone!)

Timeless appeal...

The novel first saw the day in 1844 when it was serialized, or published in instalments in popular newspapers, a popular form of literature at a time when books were expensive and reserved for the elite. It took the world by storm, was soon released as a book, and became what may have been the first international best-seller of all time, translated into more than 20 languages around the world.

Dumas turned it into a play (a two-part play, mind you, in order to sustain the suspense) and it has since been the subject of more than 30 movies and radio dramas, one of the directed by none other than Orson Welles.

The book has lost none of its appeal over time.

Visiting the Château d'If

The Château d’If is easy to reach by boat from Marseille’s Old Port, the only exception being when boats are canceled due to rough seas. The fortress is only 20 minutes away, but the return trip is usually twice as long because the boats often swing by the other islands of the Frioul Archipelago to pick up visitors and residents.

You can buy your tickets for the boat and fortress individually, or buy a City Pass, which gets you on the boat for free, as well as into the fortress.

From top of St. Christopher’s Tower, more than 45m high, you have a sweeping view of all of Marseille, so make sure you climb those steps.

Do explore every nook and cranny, and keep an eye out on the time so you don’t miss the last boat if you visit in the afternoon. You can also combine a visit to the Château d’If and the Frioul Islands for some hiking or kayaking.

Unlike the journey of Edmond Dantès, ours is an easy 20-minute ride on a modern boat from Marseille's Vieux Port

Unlike the journey of Edmond Dantès, ours is an easy 20-minute ride on a modern boat from Marseille's Vieux PortWho was Alexandre Dumas?

All this talk about the Count of Monte Cristo must have you wondering about the author.

Just who was Alexandre Dumas, exactly? Let’s have a quick biography.

His father was a brilliant military man whose mother was black, a former slave, and the author would suffer from some forms of racism throughout his life.

He wasn’t particularly well educated, but had such good handwriting he was hired as a clerk, then as a private secretary, rising through the ranks of Paris society.

He learned his literature in the literary salons of the capital, eventually traveling and becoming involved in politics before becoming the prolific writer we know of today.

Not only did he write the Count of Monte Cristo, but he is also responsible for The Three Musketeers (and its many sequels, prequels and offshoots). So prolific was he that he may have used the “help” of assistants to write, and would be criticized for this.

As royalties poured in, he became wealthy, building the Chateau de Monte Cristo, his dream estate. Here, he entertained and partied, with plenty of people taking advantage of his legendary generosity, so much so that his poor finances would eventually force him to sell it.

Dumas is buried in the Paris Pantheon, along with other famous French writers.

The Chateau Monte Cristo, Alexander Dumas's dream estate

The Chateau Monte Cristo, Alexander Dumas's dream estateBefore you go...

The Chateau d'If is on the smallest island of the Friouls, but it is also part of the Calanques National Park, which you should visit if you have the chance. You can spend a pleasant few hours visiting the Calanques on one of these tours from Marseille.