Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Destinations ›

- Loire Valley ›

- 4 Loire Chateaux

4 Chateaux of Loire valley and their conspiracy theories, lust and secrets

Published 14 August 2020 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

In all the years I've been visiting the chateaux of Loire Valley, I've loved the furnishings and gardens, but what I've loved even more are the stories, the scandals and the legends attached to their history.

Renaissance rulers may not have had social media, but they were skilled at documenting their lives: hidden sculptures, secret letters and double entendres all served to keep stories alive down the centuries. This was especially true along the secretive shores of the Loire Valley, France.

We know a lot about the shenanigans that took place behind closed doors in the fairy tale French chateaux of the Loire. Just stepping inside one is already an invitation to mystery.

I'd like to thank those who took the time to gossip and record everyone else's (and sometimes their own) indiscretions so that the rest of us might witness a snippet of the unsaid, the less savoury or the downright scandalous.

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

The Loire Valley has more than 300 chateaux and from my perspective, each is worth visiting. Today, however, we will focus on four of the most famous castles in France: Welcome to Blois, Chambord, Chenonceau and Amboise.

You might consider doing the same if this is your first visit.

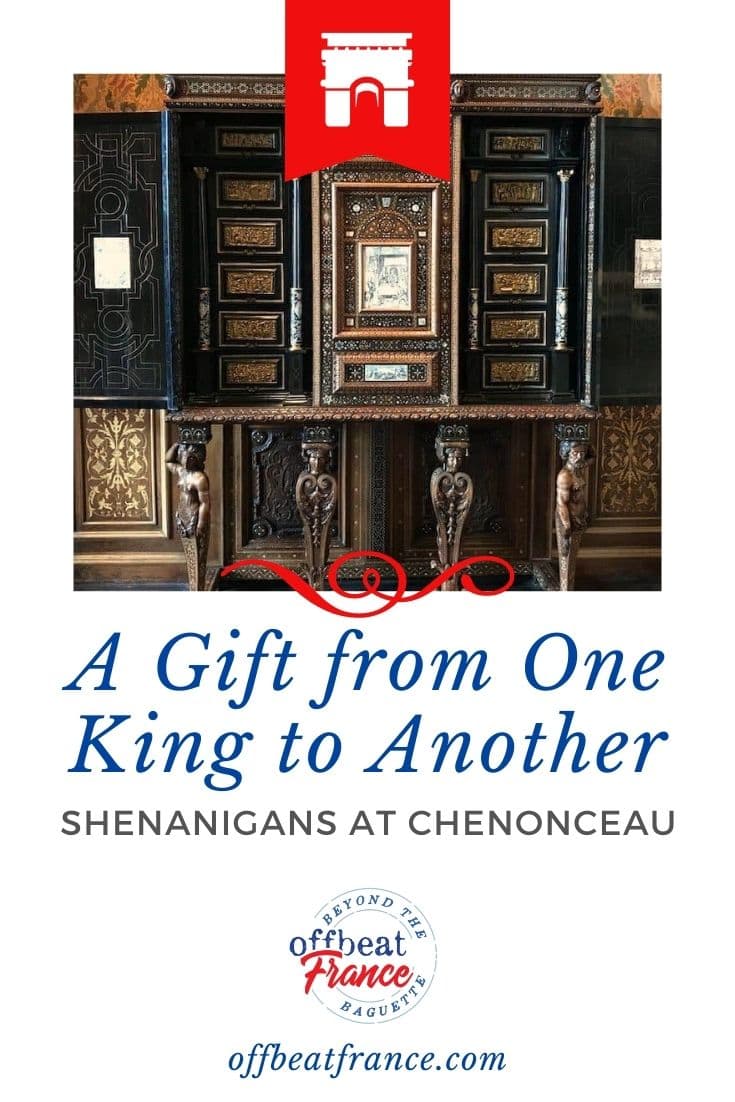

This 16th century Italian cabinet was a wedding gift to François II and Mary Stuart - although I haven't been able to find out from whom. It sits in the bedroom of François I in Chenonceau... who knows how many secrets were hidden away into those ivory and mother-of-pearl-drawers

This 16th century Italian cabinet was a wedding gift to François II and Mary Stuart - although I haven't been able to find out from whom. It sits in the bedroom of François I in Chenonceau... who knows how many secrets were hidden away into those ivory and mother-of-pearl-drawersContrary to popular belief, not all (or even most!) French chateaux are in the Loire Valley: they're everywhere! From the castle of the Dukes of Brittany in Nantes to the atypical Château de Bussy-Rabutin in the depths of Burgundy to the Cathar fortresses in the Southwest, it's hard to go more than a few kilometers in France without a castle waving in the distance.

Chateau de Blois: the favourite residence

Seven kings and ten queens lived in this castle a stone's throw from the Loire River, plenty enough to create a significant amount of mayhem. And worse...

With its Italianate balconies and arches perched high above the street, it's hard to fathom how it even got there — until you see it from the back, where gentle slopes and even courtyards provide a different perspective. That's how the building materials got up there! Gerd Eichmann / CC BY-SA 4.0

With its Italianate balconies and arches perched high above the street, it's hard to fathom how it even got there — until you see it from the back, where gentle slopes and even courtyards provide a different perspective. That's how the building materials got up there! Gerd Eichmann / CC BY-SA 4.0 And this gives you an idea of what it looks like from the OTHER side. Gerd Eichmann / CC BY-SA 4.0

And this gives you an idea of what it looks like from the OTHER side. Gerd Eichmann / CC BY-SA 4.0The assassination of the Duc de Guise

It was the late 1500s and France was being torn apart by religious wars. The Duc de Guise, a charming fellow, was much loved and respected for his (ultra)staunch catholicism. One could say he was more popular than Henri III, France's king at the time.

That did not please the king, who would play second fiddle to no one and who, unable to dampen the Duc de Guise's popularity or bring him to justice, resorted to that eternal royal fallback: murder.

On the Friday before Christmas in 1588, the duke was summoned to the king's bedroom in the Chateau de Blois. He had been secretly warned his life was in danger but his ego was greater than his fear and so, when summoned, he went.

The king's bodyguards awaited in the entrance and once the duke entered, they locked the door behind him and attacked him, stabbing him multiple times until he died.

Meanwhile the king had bravely taken refuge in his bedroom.

In the end, this did the king little good. No one rallied to his side, he was reviled and eventually excommunicated, and finally was assassinated a few months later. What goes around comes around.

Painting by Paul Delaroche of the Assassination of the Duc de Guise at the Royal Chateau of Blois

Painting by Paul Delaroche of the Assassination of the Duc de Guise at the Royal Chateau of BloisBlois is in fact 4 different castles

Usually, when you go to a chateau, you go to a chateau. One.

But when you come to Blois, you'll actually be visiting four chateaux, because it is made up of four distinct wings, built at different times, by different kings.

The fortress wing

This is the oldest, from the 9th century, in the early days when Blois was built as a fortress. All that is left from this wing is a tower and the Grand State Hall (the oldest of its kind in France) where the États Généraux met — the parliaments of noblemen.

The spectacular Etats Généraux room

The spectacular Etats Généraux roomThe Louis XII wing

Next came the pure French-style gothic castle and its iconic colonnaded gallery which lines the ground floor. You can see Louis XII on horseback in a sculpture sitting in a niche on the façade.

Louis XII on his horse - on his wing

Louis XII on his horse - on his wingThe François I wing

The Italian influence is now obvious, the result of François I's incursions into Italy. Blois is becoming a Renaissance palace, with its circular staircase and balconies fashioned after those of the Vatican. That staircase, by the way, looks a bit lopsided but it was once in the center of the building. It seems part of the building was nibbled away by Gaston d'Orléans and his own plans...

The external stairs of the François I wing

The external stairs of the François I wingThe Gaston d'Orleans wing

The newest and final wing was built in the Classical style by Gaston d'Orléans, Louis XIII's brother. He was going to be King of France since his brother had no heirs so he began adding furiously to Blois, wanting to build an entirely new chateau. He got as far as the first wing but had to stop when the future Louis XIV was born. Not only was poor Gaston shoved out as chief royal, but his funding dried up as well. Before he quit Blois, he did create a magnificent garden with more than 2000 plant species.

The chateau eventually fell into disrepair, and only escaped destruction during the French Revolution because it was given over to the army.

The Gaston d'Orléans wing is on the left, and the François I on the right. You can instantly see the difference in styles.

The Gaston d'Orléans wing is on the left, and the François I on the right. You can instantly see the difference in styles.Catherine of Medici's astrological leanings

Catherine was Francois I's daughter-in-law, married to his son, Henri II (more about him and his love triangle when we reach Chenonceau, below). She was also extremely superstitious.

She often visited Blois with her children (which included three future kings) and of course had her fortune teller with her. To help him observe the stars, which he needed for his horoscopes, she built him an observatory in the still-standing medieval fortress tower. She often spent time up there with him, discussing her and her children's futures.

She also had a more ominous reputation — that of murderous queen and poison expert. We'll never know if that was true but her enemies did seem to die conveniently. This cabinet is also said to contain hundreds of secret drawers in which, if legend is to be believed, she hid her deadly little vials.

Chenonceau Castle: Le Château Des Dames

Delightful Chenonceau! All too often, when you ask someone for their favourite Loire château, this is it!

And no wonder... with its romantic history, gorgeous interior or delicate arches over the River Cher, how can you not sigh?

Yet this little gem has a more sinister history, one that includes jealousy, friendship and revenge.

The Ladies' Château

Chenonceau is perhaps most famous for the power struggle between Diane de Poitiers (Henri II's mistress) and Catherine of Medici (his wife).

Diane de Poitiers had assisted in Henri II's birth and was eventually entrusted with his education. When he was a child of seven, Henri was sent off to Spain as a hostage in exchange for his father's freedom. She may have kissed him goodbye on the forehead, or so the story goes, his only gesture of affection on his way to exile. And he would never have forgotten.

Upon his return to France, Henri was 11. Diane was 31, and faithfully married. But then her husband died, and Henri grew up, and they became lovers.

From the moment Catherine of Medici arrived at the French court to marry Henri II (she did, by the way, fall head over heels in love with her husband), she realized he only had eyes for "the other woman", Diane (who also happened to be her third cousin).

When Henri II inherited the spectacular Chenonceau in 1547, he promptly gave it to Diane.

Diane beautified the gardens and built a wooden bridge linking the two shores of the river Cher so she could go hunting more easily on the other side.

His wife Catherine was not amused. She had loved this chateau and had designs on it herself. But things were as they were in those days and she would have to bide her time...

A chateau of such grace! You can only imagine what it looked like before Catherine of Medici had the gallery covered and two storeys added

A chateau of such grace! You can only imagine what it looked like before Catherine of Medici had the gallery covered and two storeys addedA hearty love triangle

While Diane enjoyed the castle of her dreams, it wouldn't be hers forever.

One day, Henri decided to joust at a wedding, wishing to show off his prowess (he was 40) to his mistress. His superstitious wife, watching anxiously from the audience, had a premonition and begged him not to joust. Henri went ahead, caught a lance in his eye, and soon died.

By all accounts Diane de Poitiers was a beauty.

When Henri died, she was 60 years old, and still beautiful, stunning even.

How did she do it?

She went to bed at 8pm and rose at dawn, starting each day with an ice cold bath in the River Cher. She would sneak out to bathe through a small staircase used by delivery men to ferry produce along the river to the chateau.

She also ate well, rode a lot, avoided the sun and used little makeup, no mean feat in this era of heavy face paint. Quite the modern woman, it seems.

It was a strange ménage à trois, where everyone knew one another's role and while it was far from ideal, they all made do with it.

Henri wanted his mistress, Catherine wanted children (which required Henri's cooperation) and grudgingly accepted his liaison. Diane, for her part, wanted to keep the peace and encouraged Henri to sleep with his wife. Between his wife and his mistress, he would be too busy to wander elsewhere. It worked. Catherine had plenty of children, and Diane remained Henri's mistress until his death.

Chenonceau's gallery, from the inside

Chenonceau's gallery, from the insideFinally, at Henri's death in 1559, Catherine recovered Chenonceau, swapping it with Diane for Chaumont (which some claim was a better deal for Diane, as it brought in more income).

Catherine put her indelible stamp on Chenonceau: she redecorated, upgraded the facade, added stained glass windows, and covered the once modest wooden bridge over the river — now known as the Gallery.

A fairy feast

One day, now ensconced in Chenonceau, Catherine decided to throw her son Henri III a birthday party. This was a time of high tension between Catholics and Protestants and she needed a show of power.

Remember she was from Tuscany, from Florence in fact, a city steeped in art and invention. So she commissioned one of her countrymen to come up with some majestic entertainment and decked the gardens with every possible column, statue, obelisk and other feature.

But the crowning glory designed by her Italian artist would be... a night sky illuminated by France's first-ever fireworks.

A royal gardener

Given her Tuscan origins, Catherine had brought with her to France memories of fresh fruit and vegetables the likes of which hadn't been seen much around here. Once Chenonceau was firmly in her grip, she began to plant... and plant...

Her Italian gardeners made sure her olive and citrus trees stayed healthy, and she planted artichokes and asparagus, vines and broccoli. She introduced a mysterious vegetable that had arrived from the New World with Christopher Columbus: the string bean.

She also introduced sherbets and fruit pastes, bringing the sunshine of Tuscan cuisine into the more northerly regions of the Loire.

And perhaps most noteworthy, she introduced that magical eating implement to the court: the fork.

Get thee to a nunnery

Visiting Chenonceau is a delightful experience but you won't get to see it all: some parts are hidden.

If you were to follow (it is closed to the public) the stairway up to the combles, the attic, you would come to an indoor drawbridge that once protected an unusual venue: a private convent for nuns.

When Henri III (son of Henri II and Catherine) was murdered (after having ordered the murder of the Duc de Guise if you recall), his pious wife, Louise of Lorraine, decided to mourn at Chenonceau.

She had hoped to start a community of Capucin nuns there but died before doing so. In her will, she left some money to her brother for this very purpose. Then he died, and the wish passed on to his wife, Marie of Luxemburg, who would eventually act on it.

She brought a small community of nuns to the small attic at Chenonceau, their virtue protected by said drawbridge. They would stay a few years before moving on to larger quarters in the city of Tours, and the drawbridge would close behind them, closing off their secrets forever.

A den of spies

Not all of Chenonceau's mysteries are that old: the chateau played a secret role as recently as World War II.

The castle's position linking two shores of a river made it ideal for wartime comings and goings: it so happened that one side of it was in occupied France and the other in (so-called) Free France. Refugees from the Nazi-occupied shore could transit through Chenonceau in the dead of night on their way to freedom. With the help of the Menier family, who had owned the castle since before World War I, the Resistance was able to spirit countless refugees across the River Cher.

Speaking of World War I, Chenonceau also played its part during that war. It was transformed into a field hospital and over the course of the war treated more than 2000 wounded.

Chambord Castle, super-sized

We know and love Chambord, that jewel of the French Renaissance and one of the most famous landmarks of France... its 426 rooms, 77 staircases and 282 chimneys and its fenced park, Europe's largest enclosed forest. We know it was built on a swamp as a hunting lodge for François I, and that he only spent 72 nights there in his 32 years as king of France (1515-1547).

What we may not know are the oddities hidden behind Chambord.

Chambord, so huge Louis XIV had to number its rooms to find his way around

Chambord, so huge Louis XIV had to number its rooms to find his way aroundSpending the money

François I was a bit of a show-off. Why else would he build all these royal buildings and hardly bother with some of them afterwards? He had returned from his Italian campaigns filled with wonder at the art of the Italian Renaissance, and wanted something grandiose. And newly discovered riches in the Americas promised a rosy financial future.

Despite his building frenzy, you can't say François I was particularly profligate when it came to his royal dwellings. In fact, he spent about 1% of the national budget on buildings, not altogether exorbitant.

The double helix

Most historians believe the stairway was strongly influenced by Leonardo da Vinci, who spent the last three years of his life in France. His drawings show similar stairways, some with quadruple stairs, so even though he died before Chambord was built, there is a strong likelihood that at the very least his ideas were involved.

Here's what Alfred de Vigny, the French Romantic poet, had to say about the double helix stairway:

"The base of this strange monument is, like the monument itself, full of elegance and mystery; it is a double stairway that rises in two interlocking spirals from the deepest recesses of the edifice to above the highest bell tower, to end with a lantern or opening, crowned with a colossal lily visible from far away; two men can ascend simultaneously without seeing one another."

It may feel childish but I defy you to visit Chambord and not try the experience for yourself.

Chambord, more manifesto than chateau

The utter impracticality of Chambord makes us wonder why such an insane building was ever created.

Some of the huge rooms, at 100 m2, were clearly not meant to be inhabited; heating would have been impossible, as I can assert, having visited during a freezing February.

Yet it is stuffed with symbolism, so perhaps it was more than a simple hunting pit stop.

Take the salamander, François I's emblem: in no other castle is it as omnipresent; at Chambord, you'll find it on mantelpieces, painted on ceilings, carved into doors, and lintels... yet no two are identical. It would almost seem the king was telling his story through his salamanders, which might depict such scenes as good government or his own regal qualities.

Many people see a more mysterious code in François' decor. The salamander has plenty of meanings, some of them slightly occult. It can be a harbinger of peace, which is also represented by the number 8, which is liberally scattered throughout Chambord. The chateau is studded with images of crowns, representing previous kings. And the stairway in the lantern top... goes nowhere.

Religion played a strong part in François' life: some royal monograms were printed in reverse "so that God from above can see the power of the king"!

So while Chambord's secrets have yet to be pierced, there is no denying their existence. As you wander around this unusual castle, use your sixth sense for a hint of all that mystery.

Chambord after François

Louis XIV, whose reign started about a century after François' death, would spend a lot more time in Chambord than his distant relative (Louis was a member of another branch of the family — royal successions in France are nothing if not complicated). Chambord was so big he had room numbers assigned so he would not get lost.

Chambord fared poorly during the French Revolution. The park's animals were slaughtered, whatever furniture remained was stolen, and some revolutionaries went so far as to call for the razing of such a symbol of "megalomaniacal monarch" and replacing it with modest lodgings. Fortunately they did not succeed.

Home of the Mona Lisa

Yes, we know it lives in the Louvre BUT — there was a time...

Like Chenonceau, Chambord did its patriotic duty during World War II. As the Nazis marched towards Paris, authorities feared (with reason) that works of art would be looted.

With the capital under threat, the major museums decided to organize what would become the greatest relocation of paintings in history: on 28 August 1939, some 5500 crates arrived at Chambord. Their priceless contents included the Mona Lisa (she would only stay a few months and move on to another location).

Chambord became the processing and storage center for the paintings: it closed its doors to the public and scores of art experts stood guard over artistic treasures, to keep them safe but also to make sure they weren't damaged by humidity or insects. The paintings made it through the war and were returned to their official locations.

Amboise Castle (and Leonardo da Vinci)

The best way to approach Amboise is on foot, crossing the bridge over the Loire. From the moment you catch sight of it, your eyes will gravitate automatically towards this imposing structure, however hard you try to look away. It dominates the city and unveils itself the closer you get.

Try tearing your eyes away, as the night falls... a perfect photo opportunity © L. de Serres

Try tearing your eyes away, as the night falls... a perfect photo opportunity © L. de SerresThe original chateau was built in the 5th century but obviously it was much improved over time. By the 16th century, it had become one of royalty's favourite residences. While royal children were often born at Blois, they were soon sent to Amboise for their early education. Its position atop a hill made it easy to protect the royal offspring from such dangers as escape, war, kidnapping or epidemics.

That said, they received an excellent education here, not only in languages (Greek and Latin as well as Italian and Spanish) but also science, sports and the jeu de paume, the forerunner of tennis. Along with a retinue of servants to make sure they stayed healthy and became wise...

Part of the mysterious charm of Amboise is that it is two chateaux in one: on the left, you can see it as an urban fortress, protecting the town below but on the right, seen from the rear, it is a bucolic rural retreat, filled with romance. It all depends on where you're standing.

Leonardo: his final resting place

This Tuscan genius spent the last three years of his life in France, at the request of François I. Just try to imagine this "old" man (he would have been 64 at the time), riding his mule all the way from Italy and pulling a cart filled with his belongings, including drawings, and plans, and a few of his favourite paintings. One of these bore the smiling face of a woman — the Mona Lisa.

The king would house Leonardo nearby in what is now the Clos Lucé (his studio is still on display) and would go back and forth from Amboise, a few minutes away through its many underground passageways.

When da Vinci died in 1519, he asked to be buried at Amboise and a chapel is dedicated to him right outside the castle.

For centuries, it was believed that François I held Leonardo in his arms as he died, a story that was embellished over time and even made it into several paintings. In fact, Leonardo's assistant traveled to Paris to tell François his protegé had died. The letter he carried to the king was only made public in the 19th century, revealing the king had been nowhere near the artist at his death. So you see, we're not the first to disseminate fake news...

Leonardo's studio at the Clos Lucé, a few minutes from the castle of Amboise

Leonardo's studio at the Clos Lucé, a few minutes from the castle of AmboiseCharles VIII died here too

Twenty years earlier, in 1498, another famous death had taken place at Amboise: that of King Charles VIII of France. It was a senseless accident.

Charles was on horseback, headed with his wife, Anne of Brittany, to watch a game of jeu de paume, when he smashed his forehead against the stone lintel of a door. He recovered, went on to watch the game, even spoke to a few people but then started becoming disoriented. He agonized for nine hours before dying. He was 28 years old.

Some of the doorways in Amboise may have been built low on purpose to help the castle's residents flee attack. Galloping off on a horse, a rider could simply bend down and squeeze through, something much harder to do by someone in mad pursuit wearing an armour. Perhaps Charles was distracted by the upcoming game and simply had not paid attention to the door...

Subterranean Amboise

Amboise is particularly well-known for its subterranean labyrinths and its ingenious passageways. Like many castles of its time, it required supreme organization, with many servants and guards running here and there to attend to the most minute royal needs (to give you an example, here is what a day in the life of Louis XIV at Versailles looked like).

A warren of tunnels linked the different parts of the castle, and many were used for such events as the changing of the guard, or for use to living quarters or the medieval equivalent of a staff cafeteria, the Salle des Lys.

Most impressive is the 40-meter Tour des Minimes, which has the peculiarity of being wide enough to allow a horse carriage to ascend a gentle slope and enter the castle courtyard without any passengers having to set foot on the ground.

It is also quite ingenious for its lighting, which enters the well-like structure through openings along the side and top, giving it the impression of a cathedral lit by candlelight.

After Amboise fell into royal disuse, as castles do when a better place appears, the tower was turned into a jail. You can tell by the graffiti carved into its walls.

How the Tower of the Minimes is lit from above © L. de Serres

How the Tower of the Minimes is lit from above © L. de SerresAll four of these chateaux would be beautiful and worth visiting even without such fascinating stories, but knowing about the marriages, infidelities, murders and other secrets make them even more enticing, don't you think?

Plus, they're an easy day trip from Paris...

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!