Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Destinations ›

- Undiscovered France ›

- Department Loire 42

destination: department Loire (not the loire you think!)

Say the word "Loire" and the first thing that comes to mind are the fabulous chateaux of the Loire Valley... and yes, they are stunning and spectacular and full of history.

But the Loire is a long river and at last count, more than a dozen major geographical locations carried its name.

This, the department Loire 42, is one of the more surprising and unexpected.

You could be forgiven for not knowing this irresistible home to some of the loveliest villages you’ll find in France. They’ve just hidden it well so you’ll have to earn your visit.

I’ll give you a clue: it’s south of Burgundy, and barely an hour from Lyon. I don’t live far from here – a few hours’ drive – yet I didn’t know it existed either.

This is France at its best – undulating vineyards, rugged hiking hills, deep river gorges, medieval villages and unending chateaux and churches.

Loire 42's best-kept secrets

We all have our favourites and here in the département of the Loire, I'd like to share three special sights with you. Don't get me wrong, there are many more, but... I'm afraid you’ll have to discover the rest on your own.

Gem Number 1: Villages of the Roannais

My first special highlight is a string of tiny villages with evocative names like St-Haon-le-Chatel, with its 14th-century ramparts and half-timbered houses and artists, Charlieu and its history of silk weavers, and Ambierle, with its Benedictine Abbey (whose contents were first inventoried back in 902 AD) and light organic rosé wines.

Ambierle, by the way, is home to Le Prieuré, one of the department's Michelin starred restaurants and an absolute personal favourite.

Ambierle, a gem of the Loire 42, unveiled rather than seen

Ambierle, a gem of the Loire 42, unveiled rather than seen The abbey at Charlieu

The abbey at Charlieu The quaint streets of Saint-Haon-le-Chatel

The quaint streets of Saint-Haon-le-ChatelPlease try to make time in Ambierle to visit the Musée Alice Taverne (see below), which retraces years of everyday life in the region – you’ll see dining rooms and bedrooms and kitchens filled with items that were actually used by real people in the early 1900s, a living, learning museum whose every corner is crammed with mementoes of the way life used to be.

Gem Number 2: The Bâtie d’Urfé

My second gem is part-Renaissance chateau, part fairy-tale manor house, and you'll find it further south in the lush mountains of the Forez region just south of the Roannais. It’s lovely and photogenic but more important, it has a story behind it.

Possibly more than one.

The Bâtie d’Urfé, a spot of Renaissance in the hills of the Forez

The Bâtie d’Urfé, a spot of Renaissance in the hills of the ForezIt all started with Claude d’Urfé, sent by King François I as a diplomat to Renaissance Rome. D'Urfé was so impressed by Italian art and architecture he decided to bring it home to his rural mountains of the Forez.

The Bâtie d'Urfé is a château unlike any other in the region, more Italian than French, with its double gallery and a ramp so steep horses probably skidded up or down in the rain as they carried their aristocratic charges. Claude even allowed himself flights of fancy, like the Sphinx guarding the bottom of the ramp.

The Sphinx sits as a silent symbol of wisdom, in front of the arcades of Italian influence

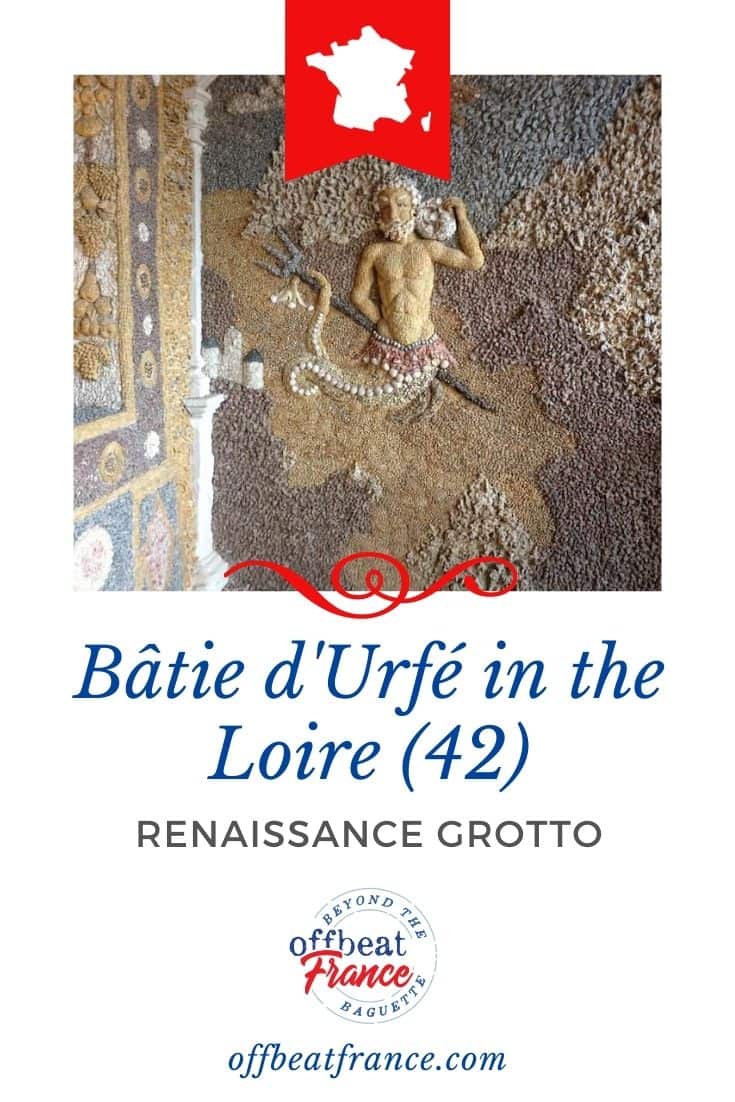

The Sphinx sits as a silent symbol of wisdom, in front of the arcades of Italian influenceOr this... rockery, for lack of a better word, an entire room made of pebbles, shells and sand, a reflection of legend, mythology and paganism.

Mythological representations mix comfortably with Italian statuary

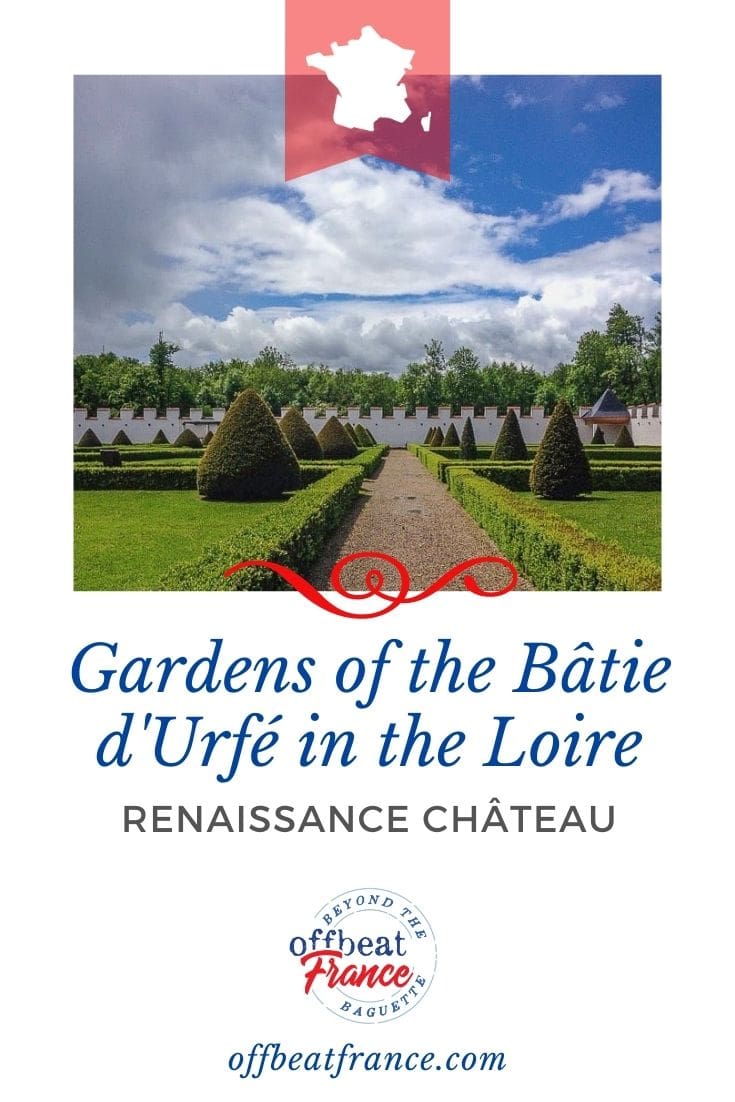

Mythological representations mix comfortably with Italian statuaryIn the best of 16th-century humanist tradition, D’Urfé created magnificent gardens tohighlight man’s domination over nature – each corner a perfect 90-degree angle asthough nature had never had a mind of her own.

Man vs nature was a recurrent Renaissance theme

Man vs nature was a recurrent Renaissance themeD’Urfé hired the best French and Italian artists of his time and created this masterpiece – all for the love of a woman, his wife Jeanne, who died at the age of 26 after bearing him six children (modern family planning methods were still far in the future).

He never remarried and continued expanding the château in her memory.

The love story goes on... Claude’s grandson, Honoré d’Urfé, is famous as the author of the 17th-century novel L’Astrée, possibly France’s first modern romantic novel. It traces the love of two shepherds, Celadon (who wore green ribbons and gave the color celadon its name) and Astrée, and takes place right in the Forez, where you can retrace the lovers’ steps. The novel is famous for its length (5400 pages over 60 books), for its complex plot and for the fame it achieved throughout Europe at a time when books were rare and expensive.

Love, of course, triumphed.

The owners of the château began to neglect it and it was only saved from destruction when a local preservation society, the Diana, bought it, had it classified as a national monument, and began extensive renovations.

Gem Number 3: Priory of Saint-Romain-le-Puy

This is a tiny gem but so are some of the best jewels: the Priory of Saint-Romain-le-Puy, ahistorical monument, is so minuscule you can see in a few minutes if you choose.

Or, you can spend a few hours allowing its treasures to gently surface.

Push the door open and frescoes of faded blues and crimsons greet you, partially defaced from a time before they were treasured. Adults still remember breaking pieces off as children.

Frescoes of the Priory of Saint-Romain-le-Puy

Frescoes of the Priory of Saint-Romain-le-PuyIf no one is around, raise your voice and listen to the echo. The acoustics are so good the priory is used for classical concerts, and I can certainly see why.

Outside, the Forez plain sweeps out in every direction. If you can get up early enough you might see the priory rise slowly from the mist.

Priory of St-Romain-le-Puy is a tiny but perfect specimen of 10th century architecture

Priory of St-Romain-le-Puy is a tiny but perfect specimen of 10th century architectureI could have spent days exploring village after village in this region but if all you have is a single day and you happen to be in Lyon aching for the countryside, a detour through the Loire will put you in a region few people visit – you’ll have it almost to yourself.

You might also like these stories!

Irresistible museums of the Loire 42

One of the things I love about France is its tradition of unusual museums; just down my own road is a cow museum and a bell museum.

If for some reason you'd like a break from all those hikes, vineyards and medieval villages, I explored four offbeat museums that were fascinating, each in its own way.

These museums speak to me for a reason: they try to protect knowledge about traditions and crafts that still existed until recently, but risk being forgotten.

Musée de la Soierie

The museum of silk (and we do all love silk) sits in an unlikely venue – the town’s 18th-century former hospital. The village of Charlieu is the ideal setting, on the other hand: about 150 years ago, when the canuts or silk workers of Lyon rebelled against exploitation, merchants broke their rebellion by bringing their business here. They turned the village into what one businessman calls the “Taiwan of Lyon.”

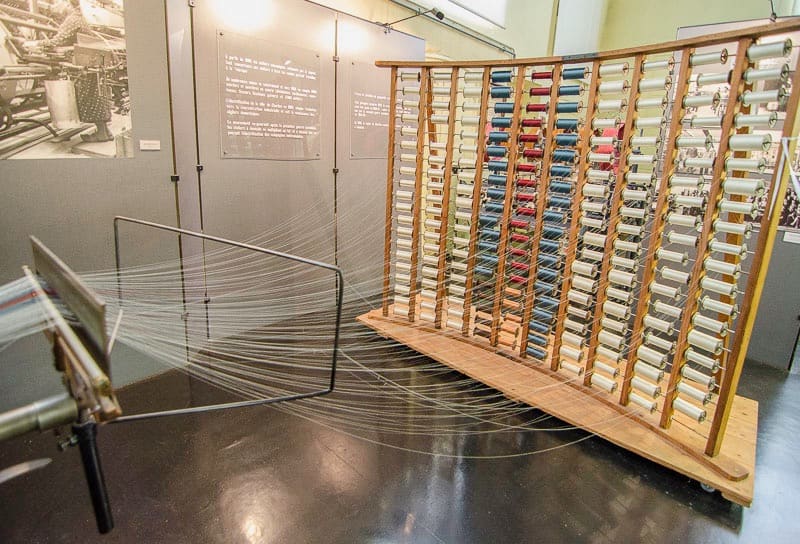

Weavers had to know exactly which bobbin to use when. These days, modern plants have taken over from painstaking manual labor

Weavers had to know exactly which bobbin to use when. These days, modern plants have taken over from painstaking manual laborWorking conditions for the 10,000 silk workers were harsh back then. Factory floors were unbearable, without electricity. No protective eyewear was available, and there was little ventilation.

The loud machines clanged incessantly, while burning steam heated the air and filled eyes, nose and throat.

Threading silk required small hands so women and often children were recruited, at low wages and, in those days, with little regard to their health.

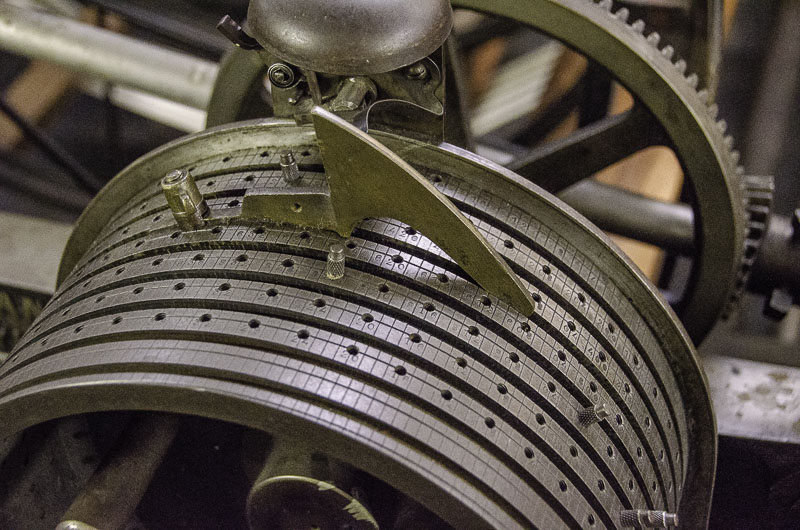

This is amazingly intricate work, with thousands of threads lined up perfectly – a single thread out of line can ruin an entire bolt of cloth. A small loom might contain 4000 threads, while a complex design on a wide cloth might require 20,000, all of which needed to end up in a precise location. Antique computers, first made of wood and then of iron, helped sort the threads, an otherwise impossible task.

Early computers at work in silk weaving

Early computers at work in silk weavingWhat used to be a thriving industry slowly dwindled in the face of cheap imports and the replacement of manpower by machines. By housing the history of French silk weaving under a single roof, the town of Charlieu paints a picture of what life in a silk factory was like. The old machines are still in working order and the shrill sound of a single one makes me wonder what the decibel level was like when dozens filled a single open space.

I had no idea making silk was so complex, from the sorting of yarn bundles, their winding into reels, the warping (placing threads next to one another until the right width is achieved), dyeing, dipping and actual weaving. Looking at a square of bright soft cloth now, I understand the hours of sweat and solitude that once went into making one just like it.

These days of course the sweatshops are gone and all that remains of the silk trade in Charlieu is a yearly celebration in honor of Our Lady of September, organized by what is now the last remaining weavers’ corporation in France, the Corporation des Tisserands.

Musée Hospitalier

Right next door to the Musée de la Soierie is the hospital museum, set in the familiar environment of what used to be the town’s religious hospital – religious because in the past hospitals were staffed and managed by the Medical Orders of the Catholic Church, not the state.

The magnificent altar in gilded wood (classified a National Monument) is dated 1733. A window opened from the inside so patients could attend mass while in bed.

The magnificent altar in gilded wood (classified a National Monument) is dated 1733. A window opened from the inside so patients could attend mass while in bed.The hospital was already mentioned in historical texts as far back as the 12 century but may have been founded even earlier by Benedictine monks, its origins shrouded in history.

It served many functions over time, including a maternity and an old men’s hospice, until it was forced to close in 1981 because the aging building simply wasn’t up to modern standards.

Looking at the spacious ward you can’t help but compare it favourably with some hospitals today, so overcrowded patients are spilling out into the hallways.

The former Hotel-Dieu hospital ward, where nuns once cared for patients; at the back, a French window opens onto the chapel so patients could follow church services without getting up

While we might appreciate the extra space, we might be less nostalgic about the obsolete medical instruments exhibited in the examination and treatment rooms.

The apothecary, just the way it used to be

The apothecary, just the way it used to beKeep walking and you’ll find a beautiful wooden apothecary, now classified as a National Monument; a linen room with giant wardrobes donated by local families to nuns taking their vows; the operating theater, a relatively modern amenity; and diverse objects reflecting the hospital’s history right up to its closure.

Hospitals are rarely pleasant but the high ceilings and spacious wards are reminders that environment can be as important to wellbeing as care.

Musée du Chapeau

If you’re as fascinated by traditions and culture as I am, perhaps the most intriguing of these four museums is located a bit more than an hour away in Chazelles-sur-Lyon. This small town in Lyon’s hinterland was famous for two centuries for its felt hats made from rabbit and hare fur. I’m not a fur enthusiast, but in their heyday in 1930, the town’s 28 hat factories employed 2500 workers.

A variety of machines were used to treat the hats as they were shaped

A variety of machines were used to treat the hats as they were shapedThe use of felt dates back to the Neolithic. Felt was used extensively in Asia for yurts and clothes and archeological digs in Pompeii found hat-making traces in that lava-entombed city as well.

Hats were hugely popular not long ago. Remember the Hollywood films of the 1930s and 1940s? It would have been unthinkable for a man or woman to be seen leaving home without a hat. By the 1960s, hats had become unfashionable and hatmakers ran out of jobs, the last factory sliding its doors shut in 1997.

Every possible shape of hat under the sun was once made here

Every possible shape of hat under the sun was once made hereNow, the art of millinery is making a modest comeback in this town. The museum has its own hat design line and collection and offers made-to-measure hats. To make sure the knowledge and craftsmanship isn’t lost, professionals pass on their knowledge to fashion students through workshops and classes.

As you leave the museum, the hats on display (made of everything from felt to feathers) in the inevitable shop attract the most attention. Men, women and children stare at themselves in the mirror, their heads covered in the tiniest or largest or brightest or most intricate hats, irresistibly drawn to the fleeting promise of a sense of glamor.

Helpful resources for department Loire 42

- You can drive to the Loire 42 in less than an hour from Lyon and just over two from Geneva. It’s autoroute all the way.

- If you can’t afford the Maison Troisgros (the lunch set menu is €120/~USD150), try Le Central, their downtown café in Roanne, with far more affordable prices.

- Or... why not take French immersion and cooking classes at the Ecole des Trois Ponts? It might not quite be Troisgros but you get to go to the market, learn about food and play in the kitchen.

- To walk it all off, the tourist office of the Roannais has a list of great local hikes. Best not to walk around the wilderness on your own – go with someone. They are woods, after all.

- The Vignoble du Roannais is well-known for a number of excellent wines and boasts recognition as an AOC.

- In Ambierle, drop by the Maison de Pays for local specialties and for the friendly young man whose name I never caught but who loves his village with contagious passion.

- The websites to the above museums are in French: Musée de la Soierie (silk) and Musée Hospitalier (hospital), Musée Alice Taverne (everyday antiques) in Ambierle, and the Musée du Chapeau (hats) in Chazelles-sur-Lyon.

—Photos Anne Sterck

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!