Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Made in France ›

- Enamels of Bresse

The Rapidly Disappearing Enamels of Bresse

Updated on 23 March 2024 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

The artistry of fine enamels of the Bresse region are under threat from machine-made items. This story takes a look at how one enameler is fighting to maintain the craft.

As machines take over crafts once fashioned by people, a backlash in France is reviving interest in handmade workmanship that requires skill, patience and centuries of savoir-faire.

Not to mention that I’m partial to affordable jewelry made by hand.

Popular with the bourgeoisie

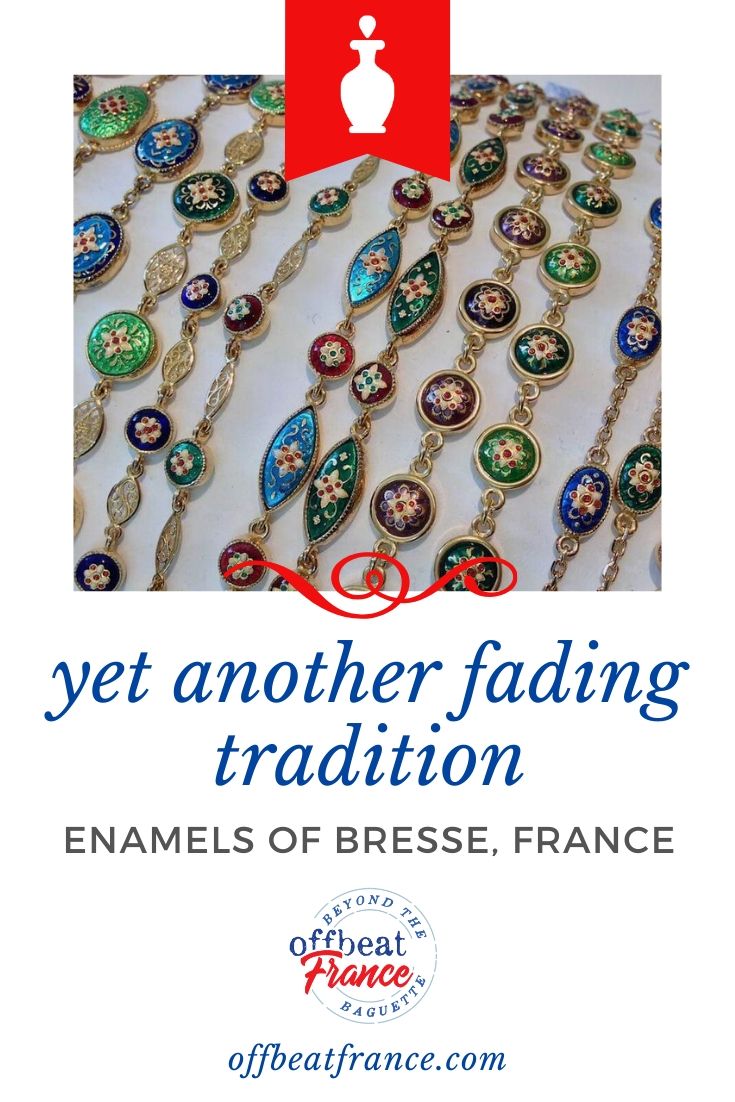

The French Bressan enamels, or émaux bressans, first appeared in the 14th century but in their present form have been around for only 200 years. With their gold leaf and tiny pearls and much-baked colors, they could not have been made by anything other than a trained, skilful and passionate set of hands.

These delicate specimens were hugely popular among the bourgeoise of Bourg-en-Bresse, a pleasant provincial capital in the Bresse region of Eastern France, better known for its award-winning chickens. The enamels were considered appropriate gifts for dignitaries, and were even sought after by such personages as the Queen of Italy and the Shah of Iran.

Enamel jewelry is relatively common but what sets these apart is the white rosace of pearls and the gold leaf filigree used at the center of each vintage necklace or pendant.

The birth of the enamels of Bresse

Each enamel is distinct and requires many highly skilled steps, which is why jewelry and watch-making are the best training for this type of work.

“It takes several years to be good at such things as cooling or symmetry. But I do my work by inspiration,” said enameler Elodie Lombard.

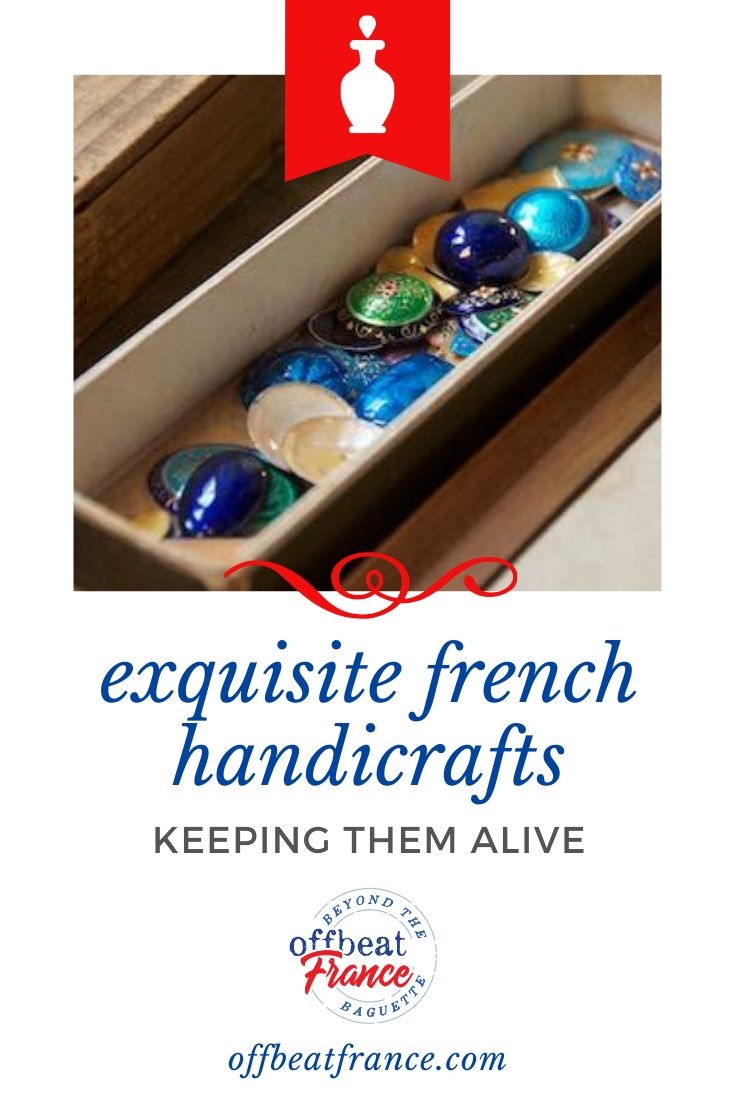

The first step involves shaping a silver base on which the enamel sits. That base is then covered thinly with enamel paste and if you don’t like the color you can add metals like copper and cobalt to liven things up. It’s then oven firing time for several minutes, about five to seven times.

After the enamel is baked, it’s time to decorate.

First comes the gold, which is bought in small balls and made into 50 gram ingots. These are flattened and laminated to the right thickness — I should say thinness — on what looks like a giant pasta-making machine.

Once the gold sheets are flattened, they are punched out into tiny shards called paillons d’or, which enamelers will then position with a tiny paintbrush, moving them around until they are perfectly placed. They’ll do the same with the pearls, so tiny those of us who wear glasses can barely see them.

Once the item is finished, the ends are soldered. The specimen is circled with a thin silver cord and filed down and hammered and a small ring attached through which a chain will be slipped.

“The pieces are tiny and the work incredibly painstaking,” said David Jeanvoine, of the Emaux Bressans Janvoine, who himself was trained first as a jeweler and then learned by doing for several years in the workshop he now manages. “It is not an easy craft. We use the same tools today that were used several centuries ago and that takes time. There are no shortcuts.”

“Each piece is unique,” he said. “We only make 2000–3000 a year because it takes time. A wide bracelet can take up to 70 hours of work.”

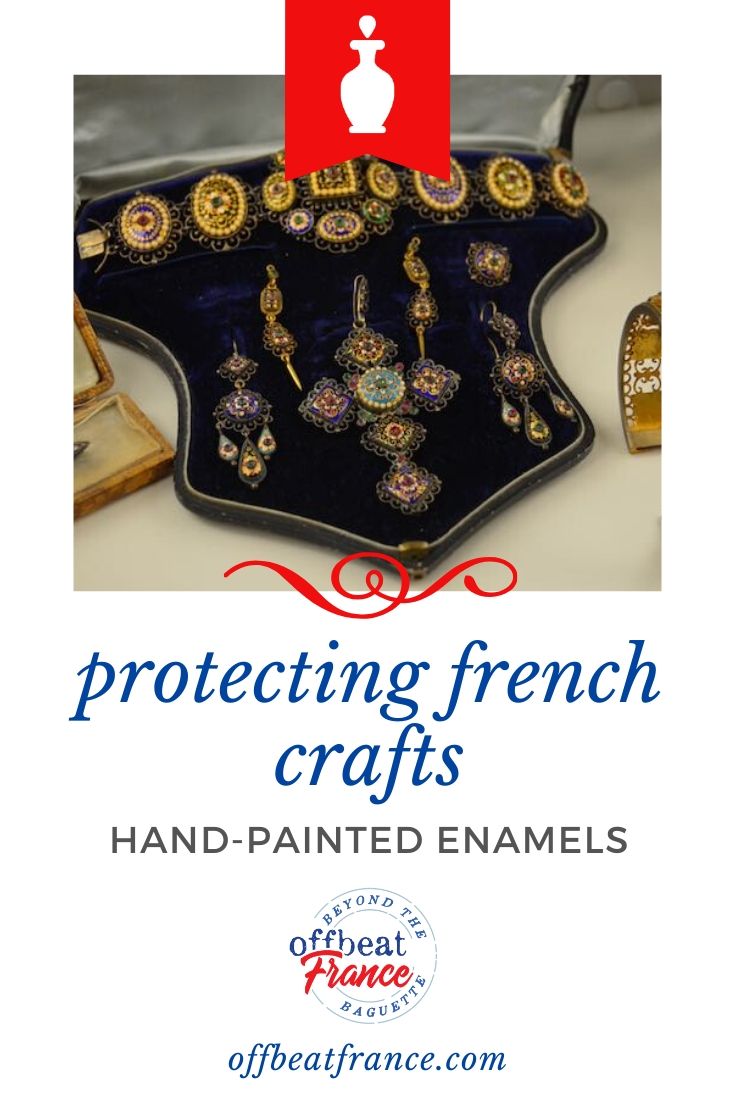

The croix bressane, or Bresse cross, a traditional piece of jewelry (on black velvet)

The croix bressane, or Bresse cross, a traditional piece of jewelry (on black velvet)One piece does stand out: the croix bressane, or Bresse Cross, which was once worn with the Bresse regional costume.

“We had to modernize. We developed new designs, introduced new colors and new shapes. We now marry ancestral workmanship with modern tendencies and this is increasingly popular,” David said.

Go for the gold

Each enameler — or artist — has his or her own personality and each one differs in the way they work. “I use this white enamel to decorate the rosace and pink pearls and it’s up to me to find a harmonious mix,” said Elodie.

Sometimes enamelers are called upon to use their craft in unusual ways. One customer, a military medal collector, brings in his tarnished and chipped medals for refurbishing. Enamel is also used for old clocks that need new faces.

This is the last workshop of its kind, yet 100 years ago the town had 10 or 20. But tastes changed, people traveled more and bought things overseas, and cheaper foreign enamels with brighly colored resins appeared on the market, undercutting local craft.

But the enamels’ future appears safe. New enamelers have been trained and growing interest in older traditions are making sure they survive.

A machine might be able to shape and paint and file a bracelet or a ring, but it takes a loving human hand to marry the whimsy, individualism and artistry of these minuscule designs.

If you travel to Bourg-en-Bresse

- You can see the enamels at Emaux Bressans Jeanvoine in the center of Bourg-en-Bresse. If you need to get in touch they don’t speak English, but email them using Google Translate.

- I stayed at the wonderful Hotel Griffon d’Or, pronounced Gryffindor. It’s managed by the delightful François and Aurélie André. Aurélie, a professional decorator, designed each room herself.

- For a simple but delicious meal try Chez La Jeanne at 4 Rue Victor Basch (here's her Facebook page), one of the city’s oldest and most famous cafés but hard to find because it has no name outside. It hosts a ‘philosophical evening’ each month where locals come to debate the great questions of life (a favorite French pastime).

- Spend a couple of hours visiting the Royal Monastery of Brou, both for its beauty and its history — it was built in the early 1500s by Marguerite of Austria as a token of love for her late husband, Philibert the Fair.

- If you are here on a Saturday, don’t miss the main market: this region is well-known for its local specialties.

- Try the poulet de Bresse, the Bresse chicken. This is the most famous chicken in France and has its own label of origin, just like wine.

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!