Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Culture & Civilization ›

- Renaissance to Republic ›

- The French Revolution

10 Startling Facts You Need To Know About The French Revolution

Published 9 July 2024 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

The French Revolution ended in 1799 but it still matters today. Understanding its key events and figures will give you insight into how it shaped modern France, from the fall of the monarchy to the revolutionary streak the French still exhibit today.

No, you don’t HAVE to know these facts about the French Revolution when you visit France.

But if you do know them, they’ll help you understand why France is the way it is – why we’re always taking to the streets, why we no longer have a king, how we ended up with Napoleon... along with the heroes and heroines behind nearly every street name.

It’s a term we bandy about a lot, the “French Revolution”, a bit of a catchall for everything that is both right and wrong in my country. But knowing a little something about this cornerstone event means you’ll enjoy your visit even more.

What exactly was the French Revolution?

10 fun and unexpected facts about the French Revolutio

- 1. The French hated Marie-Antoinette

- 2. The Reign of Terror was the work of an obscure provincial lawyer

- 3. The Revolution upended the powerful Catholic church

- 4. Napoleon would not have ruled France without the Revolution

- 5. The Revolution gave women equality (and then took it away)

- 6. The guillotine was not invented during the Revolution

- 7. One revolutionary leader conducted business from his bathtub

- 8. A key revolutionary decision took place on a tennis court

- 9. The Revolution overhauled France’s measuring systems

- 10. The 2024 Paris Olympic mascot is actually a revolutionary symbol

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

What exactly was the French Revolution?

Whatever the details, it turned France upside down.

Ordinary citizens challenged the power of the king and the nobility, and absorbed new ideas put forth during the Enlightenment. It was a dramatic chapter in France’s history and it would reshape the country, not to mention the world, inspiring future movements for democracy and human rights.

But let's backtrack a bit.

The country had gone into massive debt from the Seven Years' War and the money it spent on the American Revolution, so the popular finance minister had been dismissed, the economy was in a mess, and people were hungry and resentful towards those who ate their fill.

It was decided to reconvene Parliament to try to sort things.

For centuries, France had had a so-called parliament: the Estates-General, which represented the three “estates”, or levels of society. The First Estate (clergy) and Second Estate (nobility) enjoyed a life of wealth and privilege, while the largest, the Third Estate (commoners), paid the most tax and had little political power.

This parliament may have existed on paper, but in reality, the Estates-General hadn’t met in 175 years. It was a bit rusty, yet it was supposed to fix the country’s finances. It would of course fail, opening wide the door to revolution.

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION: A SNAPSHOT

- Revolutionary rumblings would begin to spread around 1787

- By 1789, the monarchy would be overthrown

- For ten months in 1793-94, a violent Reign of Terror would lead to thousands of executions

- A five-member Directorate would take power but and last from 1795-99

- An army coup led by Napoleon Bonaparte would overthrow it in 1799, replacing the Directorate with a Consulate. Napoleon would become First Consul and crown himself Emperor in 1804.

These were the days when philosophers like Voltaire, Rousseau and Montesquieu all called for a more egalitarian society. They criticized absolute monarchy and championed the Enlightenment ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

These ideals would provide a kind of intellectual justification for the overthrow of the old order and the creation of a new one, which would be based on reason and justice.

At least that was the theory, and of course it didn't quite turn out that way.

Why should you care?

Wherever you turn in France, you’ll come face to face with some facet of the Revolution. So if you come here, or even if you're reading about France out of interest, you'll understand the country far better and more quickly if you know something about one of the biggest events in our history.

- It gave us some of our most memorable stories: the women’s march on Versailles, the absurd wealth of Marie-Antoinette, the beheading of Louis XVI, the fall of Robespierre and the rise of Napoleon. All this was more than just human drama: it was epoch-changing upheaval played out on what was then a world stage.

- It overhauled human rights. France had a feudal system before the Revolution, with the nobility and the clergy at the top, at the expense of most of the people. With notions of equality contained in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, our bill of rights would be born.

- The Revolution spread from France. It fueled the Haitian Revolution, inspired the Latin American wars of independence, and influenced European political thinking for generations.

- With the storming of the Bastille, revolutionaries weren’t just breaking into a prison – they were making an assault on oppression and disparity. Take Versailles: when you visit, you’ll find it opulent, absolutely over-the-top. Imagine how people must have felt watching royalty cavort in the gardens while they fought to find bread for their families!

- It provided us with new concepts such as secularism, nationalism, and the separation of church and state.

- For better or worse, the way we structured our future National Assembly set the scene for parliaments worldwide.

- The Revolution created art, which depicted revolutionary fervor and ideals. Jacques-Louis David's paintings are typical of the Revolution.

- Everywhere you turn, you’ll see names – on streets, shops, metro stations – linked to the Revolution. As you navigate across France, look at those street names and ask yourself: “Who were these people?” Many of them would have been revolutionaries.

Versailles depicted unimaginable wealth. Rumors of gold and crystal rooms had made their way through society, even to the poorest, who could no longer accept the disparities.

Versailles depicted unimaginable wealth. Rumors of gold and crystal rooms had made their way through society, even to the poorest, who could no longer accept the disparities.10 Intriguing facts about the French Revolution

The Revolution was central to what France is today, but beyond the history books, there are stories. Many stories., and here are just a few of them.

1. The French hated Marie-Antoinette (often because of fake news)

King Louis XVI simply couldn’t get the economy under control. Having sacked his finance minister, he dug in his heels, and the more stubbornly he clung to power, the more his authority weakened.

His eventual (and unsuccessful) attempt to flee France with his family and seek foreign help made him even more of a pariah figure.

If anything, Queen Marie-Antoinette embodied the hated elitist regime more than her husband, and when people sought a scapegoat for their troubles, they turned to the foreigner.

To them, she represented royal excess and insensitivity, leading a life of luxury and extravagance while they starved. The famous but probably untrue phrase "Let them eat cake" showed how disconnected the monarchy was from the people's suffering.

Also, the fact that she was Austrian made people suspicious. She was accused of meddling in state affairs and blamed for many of the monarchy’s unpopular decisions.

But she was also blamed for things she didn’t do.

Portrait of Marie-Antoinette by Joseph-Siffred Duplessis. It now hangs at Versailles Palace. Photo APK CC BY-SA 4.0

Portrait of Marie-Antoinette by Joseph-Siffred Duplessis. It now hangs at Versailles Palace. Photo APK CC BY-SA 4.0The most famous example is undoubtedly the Affair of the Diamond Necklace.

A greedy woman at court had cast her eye upon an expensive diamond necklace. It had originally been crafted for Marie-Antoinette, but the Queen turned it down because of its cost. The courtier in question, Jeanne de la Motte, forged the Queen’s signature and convinced a gullible cardinal to help her buy the jewelry. Once the fraud became public, Marie-Antoinette was somehow blamed, even though she knew nothing about it.

Still, fair or not, her excessive lifestyle didn’t help her popularity. Revolutionary propaganda exaggerated things and branded her as manipulative and morally corrupt, so that by the time of her execution, she was indeed despised.

Louis XVI was decapitated on 21 January 1793, and his wife, Marie Antoinette, on 16 October the same year.

2. How an obscure provincial lawyer became responsible for thousands of deaths during the Reign of Terror

Maximilien de Robespierre was a small-town lawyer who became influential through his strong beliefs in equality and justice for ordinary people.

But it all went terribly wrong.

In 1793, he joined the powerful Committee of Public Safety, a group responsible for the country's defence and internal security. Under his leadership, the committee would root out and punish anyone considered an enemy of the Revolution. This would spiral into a ten-month period known as the Reign of Terror, during which thousands would die by the guillotine, including former allies and innocent citizens.

Despite the Reign of Terror he ushered in and the many deaths for which he was responsible, Robespierre’s name graces street plaques all over France, mostly because of his ideals of equality and justice (no matter how wrongly they were eventually applied)

Despite the Reign of Terror he ushered in and the many deaths for which he was responsible, Robespierre’s name graces street plaques all over France, mostly because of his ideals of equality and justice (no matter how wrongly they were eventually applied)Robespierre believed that extreme measures were justified to achieve a just and equal society, and that extremism would ensure the survival of the new government. For him, terror was a tool for good – it would protect the Revolution and keep it pure.

Eventually, the widespread fear and the constant executions (17,000 "enemies" were guillotined) began to turn people against Robespierre. Many saw his extreme actions as a betrayal of the revolution's original ideals of liberty and justice.

In July 1794, in a classic case of what goes around comes around, he too was led to the guillotine and executed by his former colleagues, marking the end of the Reign of Terror.

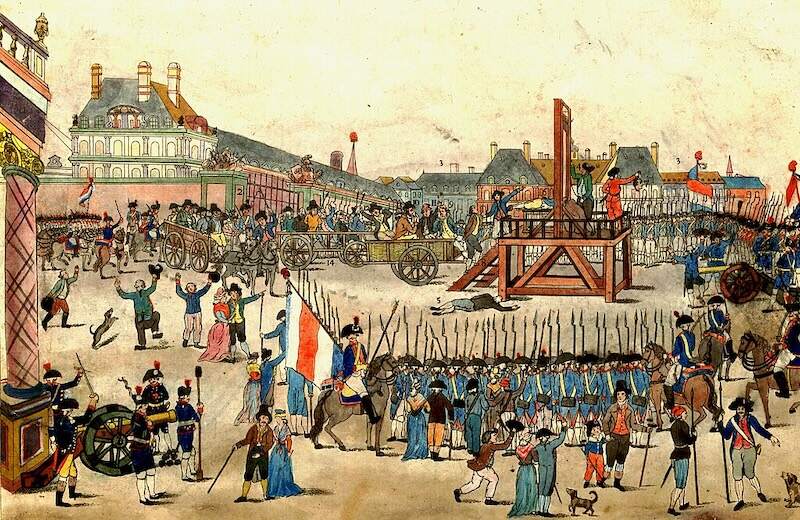

It is 28 July 1794 and Robespierre, sitting on the cart, is awaiting his execution. He is dressed in brown, is wearing a hat and holding a handkerchief to his mouth. Augustin, his younger brother, is climbing the scaffold steps.

It is 28 July 1794 and Robespierre, sitting on the cart, is awaiting his execution. He is dressed in brown, is wearing a hat and holding a handkerchief to his mouth. Augustin, his younger brother, is climbing the scaffold steps.3. The Revolution upended the powerful Catholic church

Before the Revolution, the Catholic Church had been the most powerful institution in the land (after the French monarchy, of course).

The revolutionary government was keen on doing away with the clergy and separating church and state.

A new law, the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, tried to reorganize the church based on France’s administrative divisions (the then 83 departments – today we have 101). The people would elect one bishop per department, and the French government would pay their salary.

The government then abolished the tithes (which earned the Church its income) and took over its lands, injecting a sizeable chunk of wealth into revolutionary coffers along the way.

Clergy were required to take an oath of allegiance to the state or lose their parishes: only half did so, tearing the Church apart. Then, the Pope condemned the state’s demand, and a holy mess ensued, with non-oath-taking priests punished as enemies of the state.

The disarray would only end under Napoleon, whose Concordat of 1801 committed both sides to compromises, ending the schism.

In an intriguing aside, the leader of the Revolution, Robespierre, tried to replace Catholicism with something called the Cult of the Supreme Being. This involved a festival, led by Robespierre prancing around in a toga. What a sight that must have been.

Once Robespierre died, the cult died with him.

The Festival of the Supreme Being. Painting by Pierre-Antoine Demachy (1794), via Wikimedia Commons

The Festival of the Supreme Being. Painting by Pierre-Antoine Demachy (1794), via Wikimedia Commons4. Napoleon would never have gained power without the Revolution

Napoleon Bonaparte was a product of the Revolution, which changed society and replaced birth with talent as the prerequisite for getting ahead (most of the time, anyway). This allowed an unknown Corsican officer – gifted with a brilliant strategic mind – to gain prominence through military victories, even without the right family connections.

Napoleon was so good at winning wars that he eventually staged a coup d'état, overthrowing the government and establishing himself initially as First Consul, and eventually as Emperor.

By promising not to reverse the gains of the Revolution, things like secularism and the abolishment of the feudal regime, he gained the support of all those who had benefited from these reforms.

Without the Revolution, it’s safe to say there would probably have been no Napoleon. There would have been no need for a strong leader to wean France from the violence and end the chaos.

Napoleon in Lyon, overseeing his troops before the Egyptian campaign which would help cement his reputation. Photo Archives municipales de Lyon via Wikimedia Commons

Napoleon in Lyon, overseeing his troops before the Egyptian campaign which would help cement his reputation. Photo Archives municipales de Lyon via Wikimedia Commons5. The Revolution gave women equality (and then took it away)

In October 1789, in the early days of the Revolution, thousands of women marched to Versailles to demand bread and force the royal family to move back to Paris where the people could keep an eye on them.

Two years later, the writer Olympe de Gouges published the Declaration on the Rights of the Woman and Citizen, declaring the full equality of women, a radical idea at the time.

Before the Revolution, women had been considered minors, similar to children. They couldn't inherit property, participate fully in public life, or make important decisions without the permission of their fathers or husbands.

The Revolution changed all that: new laws limited the power of men over their families, legalized divorce, and finally gave women the right to conduct all sorts of business without male permission. The new laws also decriminalized homosexuality and removed the requirement for unmarried or widowed women to declare their pregnancies under threat of death.

But these gains wouldn’t last.

By 1793, there was a backlash and women were again excluded from political life, their clubs shut down, and many of their new rights taken away. Things became even worse under Napoleon, who made women legal minors again.

Still, the Revolution did lay the groundwork for future feminist movements, even though major advances in women’s rights would have to wait nearly a century.

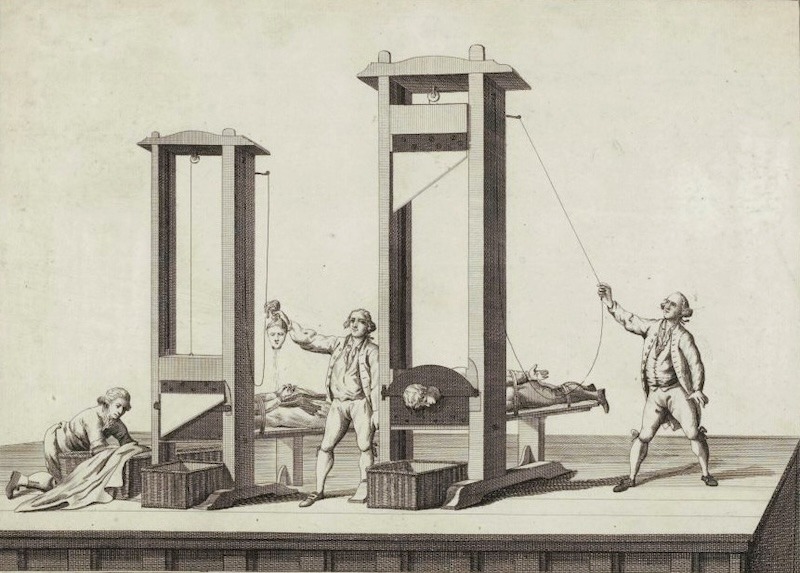

6. The guillotine was not invented during the Revolution

There’s a widespread belief that the guillotine was invented during the French Revolution but… no.

This instrument of execution had a long history: decapitation machines already existed in the 16th century in Italy (the mannaia) and in Scotland (“The Maiden”). A certain Dr Joseph-Ignace Guillotin used them for inspiration for his own machine, designed as a humane method of execution to provide a quick and “painless” death. (Before the guillotine, executions were brutal and often botched, more a form of torture than of death.)

The last execution by guillotine would take place in 1977, and the contraption, along with the death penalty, would be outlawed in 1981.

The guillotine is considered as a cruel form of execution, yet it was initially designed to be humane in a brutal era

The guillotine is considered as a cruel form of execution, yet it was initially designed to be humane in a brutal era7. One revolutionary leader conducted business from his bathtub

Jean-Paul Marat was a prominent revolutionary leader and journalist during the Revolution.

He had a severe skin condition that forced him to spend a lot of his time in the bathtub, so he used it as his office. But that didn’t stop him from being a fervent advocate for the Revolution, penning inflammatory articles and rallying the people from the bottom of his tub.

All this ended in July 1793 when Charlotte Corday, a young woman who opposed his radicalism, talked her way into his home (she pretended she was delivering crucial information) and stabbed him while he was bathing.

The assassination became one of the Revolution’s most symbolic events: Marat was attacked while defenceless, and portrayed as a martyr who died for his ideals. The fact that his assassin was a woman came at a time when gender roles were being revisited: to some, she was a hero, but to others, she was undermining the Revolution.

The event was immortalized in Jacques-Louis David's iconic painting, "The Death of Marat".

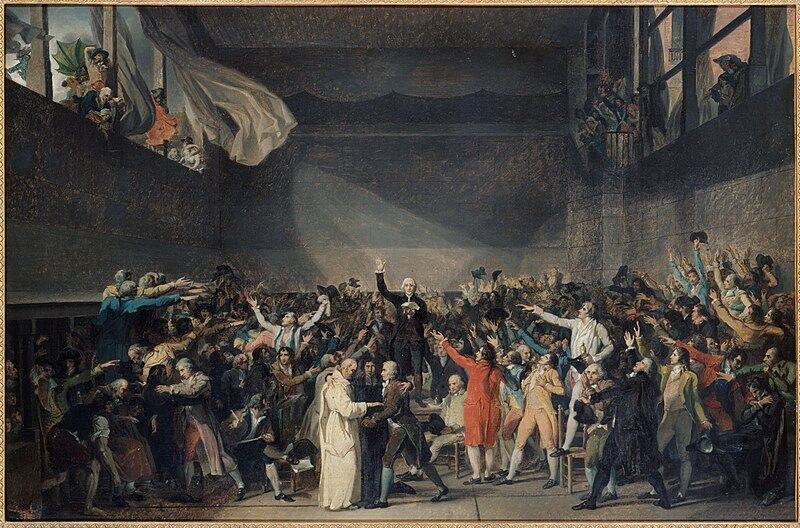

8. One of the most important revolutionary decisions took place on a tennis court

In the Revolution’s early days, in June 1789, the “people” and their allies, the Third Estate, were planning to meet but when they showed up at the meeting hall, the doors were locked and guarded by royal troops who wouldn’t let them in.

Instead, they gathered in one of Versailles’ indoor tennis courts and vowed they wouldn’t leave until they had drafted a new French constitution.

This act of defiance became known as the Tennis Court Oath, or the “Serment du Jeu de Paume” again commemorated by artist Jacques-Louis David. It would become, like the taking of the Bastille two weeks later, a major symbol of the Revolution.

Le Serment du Jeu de Paume. Bailly, standing on a table, facing the spectator, Robespierre on his right, Maupetit invalid, on the left, led on a chair, three men of the Clergy (regular, secular and pastor) in the center in front of Bailly. Painting by Jean-Louis David

Le Serment du Jeu de Paume. Bailly, standing on a table, facing the spectator, Robespierre on his right, Maupetit invalid, on the left, led on a chair, three men of the Clergy (regular, secular and pastor) in the center in front of Bailly. Painting by Jean-Louis David9. The Revolution overhauled France’s measuring systems

A major goal of the Revolution was change, often for its own sake, discarding the old and embracing the new, whether it made sense or not. Often, though, it was simply a case of doing away with anything hinting at religion or royalty.

Some of the changes would be enduring and practical, like the metric system, while others, like the revolutionary calendar, would be short-lived.

France before the Revolution was a patchwork of provinces with many systems, including measurements. Think about it: before the Revolution, at least 250,000 different weights and measures were in use. No wonder the Revolution wanted to standardize things!

In 1795, it did just that.

A new measuring system was developed by the best of the Enlightenment thinkers. The metric system would be based on nature, and the meter would be one ten-millionth of the distance from the North Pole to the equator. Every measure would be based on the decimal system, always being a multiple of 10 – 10 millimeters in a centimeter, 1000 grams in a kilogram, and so on.

People often dislike change and there was plenty of pushback. Napoleon even abandoned the system in 1812, but like many good ideas, it resurfaced until finally, in 1840, it was reinstated and is now a cornerstone of commerce and science worldwide.

Less fortunate was the fate of the new revolutionary calendar.

The French Republican Calendar was also based on the decimal system, but this went too far.

Every month had exactly 30 days, made up of three “decades” of ten days each (rather than the traditional seven-day week). Each day had ten hours, an hour had 100 minutes, and a minute had 100 seconds.

The new system also gave each month a new name reflecting the weather around Paris, then, as now, considered the center of the universe. So February, or parts of it, would be called Ventôse, from the word for windy. And July-ish would be called Thermidor, from the Greek for summer heat.

It might have made sense on paper but… surprise, surprise: it was impractical, unpopular, and was abandoned in 1805.

It would resurface for a few days in 1871 during the Paris Commune, but soon disappear, never to be heard from again.

10. The 2024 Paris Olympic mascot is actually a revolutionary symbol

Also known as the "Liberty Cap," the red Phrygian Cap symbolized freedom and resistance to oppression. In 2024, it was adopted as the “mascot” of the Olympics and Paralympics, a familiar French symbol. France decided it would have a symbol for its games rather than the traditional animal mascot.

The cap has its roots in Antiquity and became synonymous with freedom in Roman times. During the French Revolution, it became a symbol of freedom for revolutionaries.

1793

1793 2024

2024Suggested books about the French Revolution

- A New World Begins, by award-winning historian Jeremy Popkin

- The French Revolution, by Ian Davidson, with a fresh look

- Citizens, by Simon Schama, New York Times bestseller

- Twelve Who Ruled, by R. R. Palmer, who looks at the Reign of Terror

Before you go…

Now that you know everything (almost) about the French Revolution, put your knowledge to the test next time you visit Paris by hopping on one of the several excellent French Revolution tours being offered in the capital.

A lot of the sites may be more meaningful once you understand the history behind them.