Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Destinations ›

- Lake Geneva-French Alps ›

- French Alpine Cheese Board

How To assemble The Perfect French Alpine Cheese Board

Published 04 October 2020 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

I live along the Rhône River, sandwiched between the Alps and the Jura Mountains – and both are renowned for their French Alpine cheese – here I'll tell you about them, and show you how to prepare the perfect cheese board.

French Alpine cheese includes some of the best mountain cheeses in the world – and they're every bit as good (and sometimes better) than their Swiss cousins.

The changes in climate and vegetation, the mountain air, the distances and the various animal breeds – everything contributes to the delicious diversity of the cheeses of this region.

Whether it's for your cheese platter or for that dusty fondue set sitting at the back of your cupboard, these cheeses will remind you just why eating a fromage fresh from the Alps is more than a meal: it's an experience.

But before we set out to suggest what goes on that cheese tray, let's take a closer look at the cheeses. They are, after all, the stars of the show.

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

A bit of alpine cheese history

Cheese may have been discovered accidentally, a sobering thought for something that has become such a staple of our lives. It is thought that cheese first appeared as far back as 8000 BC. As milk was stored in animal skins, a combination of warm weather and rennet from the animal stomachs in which it was stored may have caused the milk to curdle, and Presto! The first cheese...

Here in the Alps, traces of Alpine cheeses date back to the Middle Ages. In those days, artisanal know-how and traditions were handed down from one generation to the next.

High in their isolated mountains, herders and shepherds battled altitude and difficult climate, learning to adapt by doing the right thing at the right time of year.

That path is still followed today.

The French Alps, in all their glory

The French Alps, in all their glory- Spring: this is when herds are taken outdoors after a long winter in the stables; the snow melts and the greenest of grass is ready to be eaten.

- Summer: the herds go higher into the mountains, where the grass tastes of flowers. Just below, farmers cut the grass and store it for winter.

- Fall or autumn: farmers remove the fencing that had kept animals from wandering too far and the herds are brought back down from the mountains.

- Winter: animals will stay indoors, fed with the grass that was cut for them a few months ago. In this way, a finely tuned seasonal dance takes place, today as it did centuries ago.

Some things did change along the way, though.

A first major agricultural revolution in the 17th century came with conservation advances, which allowed cheeses to be kept a long time and were easy to carry. Business became good, evidenced by the spate of building of baroque churches throughout the mountains in the 17th and 18th centuries in communities rich from their alpine cheeses.

Then, in the 19th century, mechanization threatened traditions but the cheeses were saved by farmer cooperatives and by labels designed to protect their artisanal nature.

That doesn't mean there is no large-scale production of French Alps cheese – it just means that when you buy or taste one of the protected cheeses, you can be certain it was made by hand, in pretty much the same way it has always been.

What exactly are French alpine cheeses?

There are several types of French cheese: fromage frais, goat cheese, soft cheeses, veined cheeses, pressed cheeses and spreadable cheeses. Alpine cheeses are mostly pressed, and they are made in the French alpine départements of the Savoie and the Haute-Savoie.

These Savoy cheeses are made from unpasteurised milk and are called pressed cheeses because the curd is pressed to remove as much whey as possible (whey is the liquid left behind once the milk coagulates).

In case you're curious about these things, there are different kinds of pressed cheeses:

- uncooked, in which the curd is only slightly heated, which keeps the cheese soft on the inside; this includes the Tome des Bauges, Tomme de Savoie, Chevrotin and Reblochon

- semi-cooked, like Abondance

- cooked, like Beaufort and Emmental

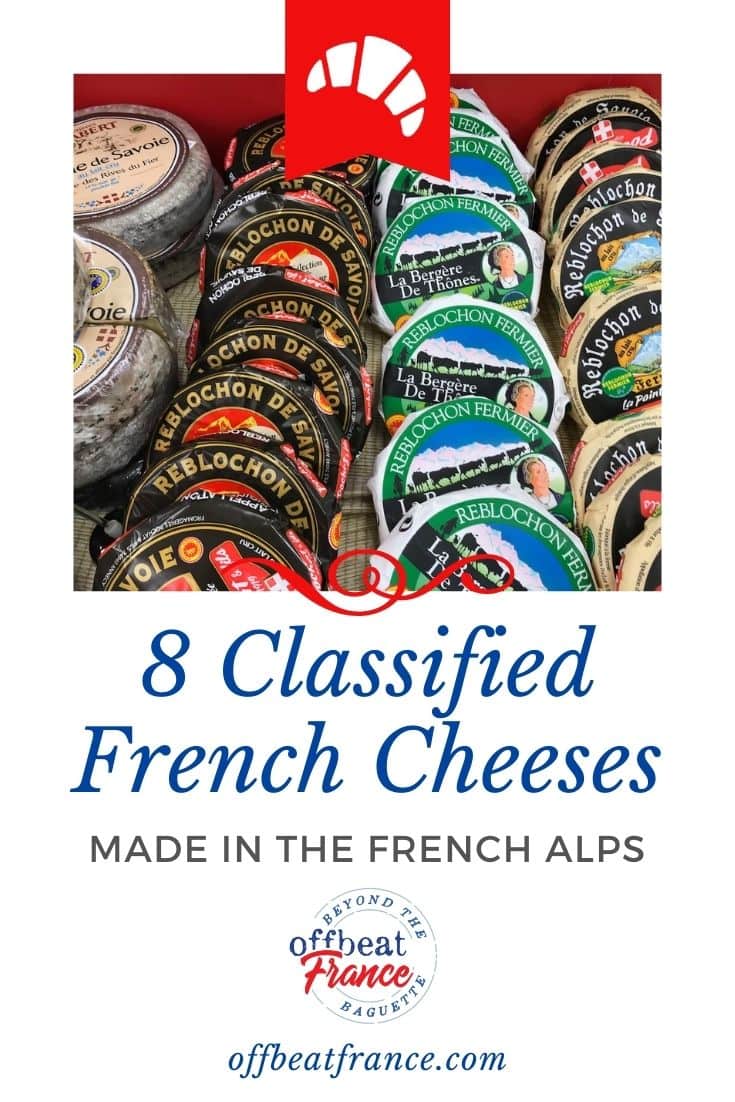

Eight specific cheeses qualify as Fromages de Savoie, or Savoy cheeses: they are, in no particular order, Beaufort, Abondance, Reblochon, Emmental, Tome, Tomme, Raclette and Chevrotin. They are made from unpasteurized milk.

They also share a nutty taste with a hint of grass, the product of the high Alpine meadows in which its cows and goats graze. Traditionally, the cheeses are made with milk from the Abondance, Tarine or Montbéliarde cows.

How can you govern a country which has 246 varieties of cheese?

—Charles de Gaulle

Each of these is protected by one of two labels: AOP, Appellation d'Origine Protégée, or IGP, Indication Géographique Protégée.

The AOP certifies that "everything, from the raw material to the processing and the final product, comes from one clearly defined region of origin". The IGP label means something is either produced, processed or refined in its place of origin.

These guarantee the quality and provenance of each cheese and confirm that it is made in a certain way, using certain methods and products. In other words, a guarantee of consistency and excellence at every level.

In addition to the eight, many other cheeses are made in this region, including the Termignon blue (one of the most expensive cheeses) or the Tamié, a Reblochon-like cheese produced at the Abbey of Tamié since the Middle Ages.

Where do you buy French alpine cheeses?

You can of course buy these cheeses in the valleys, in supermarkets or specialist shops. But you can also buy them at the source, in the mountains where, for some reason, they seem to taste better.

Here are the different kinds of places you can either taste or buy cheeses:

- regional shops, often in village or town main streets

- online, from specialised sites

- in a fromagerie, a specialist cheese shop

- in a cooperative, where farmers pool their products

- in a fruitière, a traditional mountain cheese cooperative

You'll find the latter three scattered throughout the mountains...

The 8 types of French cheese from the Alps

Wheel of fortune: Beaufort cheese

If you’ve tasted Beaufort cheese – incredibly creamy yet sharp – you’ll probably remember it. It is faintly similar to Gruyère or Emmental (without the holes) – but Beaufort is unctuous, luxuriant and, in my humble opinion, even tastier.

Beaufort got its name for a small Alpine village of wooden chalets in the region of the same name (Beaufortain), in the eastern part of the Savoie.

It’s hard to avoid Beaufort in the Alps. At village fairs or markets, large slabs or gigantic wheels fill every stall and to entice clients. Cheese sellers cut it into tiny squares they leave on a plate with toothpicks. Don’t be shy when you see these ‘tasters’ – grab one and let it melt on your tongue. Try walking away.

You can’t have just one square – you’ll keep coming back for more. Not for nothing is it called the ‘Prince of Gruyères’.

And don’t eat Beaufort alone. Like all mountain cheeses, it goes well with white wine. Try it with a nice white Burgundy or Chablis, with a more local Apremont or Chignin, or with a young ‘vin jaune’ wine from the Jura region.

Beaufort is wonderful on its own but great for cooking too – try it in a quiche (see the recipe), in a cheese fondue (mixed with Gruyère or Emmental, in a grilled cheese sandwich, or... with smoked salmon on the side!

Many Alpine cheeses were first made in monasteries. Medieval mountain monks were the first to make Beaufort but in the 1960s Beaufort almost disappeared. Young people left the mountains for a more hip or wealthier life in the city, but cheese production needs a lot of work and there weren’t enough workers left. Farmers reacted by setting up cooperatives to share costs of production and marketing.

Beaufort is a huge cheese – it is 60 cm (two feet) across, weighs as much as a young adult at between 40-60 kilograms (90-130 lb) and stands 16 cm (6 inches) thick.

And it is a hungry cheese, requiring 500 liters (130 gallons) of milk for every 45 kg (100 lb) of cheese. This is not a cheese you can take lightly.

Here's where you can find Beaufort cheese..

A Beaufort quiche – known as Tarte au Beaufort – is not to be messed with.

Line a round pan with pastry (and don’t forget to prick the bottom of the pastry with a fork).

In a bowl, beat 2 tablespoons of fresh cream, 2 eggs, half a liter of milk and a sachet of yeast. Grate in 150g (5 oz) of Beaufort and a bit of nutmeg, and beat until light and frothy. Pour it into the pastry and cook in a 220°C/420°F oven for 30 minutes.

Of popes and kings: Abondance cheese

The first time I tasted Abondance, it was by accident. I was on a writing assignment in the far northern Alps and stopped for a snack at the Saturday morning market in the town of the same name.

What a happy accident!

Creamy Abondance cheese by Coyau / CC BY-SA 3.0

Creamy Abondance cheese by Coyau / CC BY-SA 3.0This must be the most irresistible cheese in the entire Alps and the most impossible to stop eating, a gourmet cheese with a history stretching back nearly seven centuries.

Abondance was first made by the monks of the same name in the Monastère d’Abondance on the nearby Swiss border. They cleared the forests to create meadowland and then rented it to farmers, who paid in cattle – the Abbey provided the farmers with cauldrons for cheese making.

Abondance has an illustrious and long history. In 1381, during the Avignon conclave to elect a pope, 15 quintals (nearly 750 kg/1.6 tons) of Abondance cheese were ordered and delivered. Similarly, Louis XIV, the Sun King, had a predilection for this unctuous cheese.

Abondance, like Beaufort, is made from whole raw milk and a taste so distinctive it is best eaten on its own, perhaps melted down as Raclette.

It is also pretty good in Berthoud (see recipe below). Abondance is smaller than Beaufort, and usually weighs about 7-12 kg (15-25 lb), with a brownish yellow rind under which lies a layer of gray. Its edge is concave – it curves inwards at the edges so you can easily tell it apart from the others.

Abondance has a strong smell (though its taste is lighter) and should be accompanied by a Marin, Crépy, Ripaille or Crémant de Savoie, or a Côte de Nuits Villages. Some experts also recommend Syrah grape wines. Abondance is a tasty snack while you’re walking around the market, too!

Here's a map of Abondance producers.

Abondance is perfect for the Berthoud, a simple mountain recipe for cold winter nights.

Cut thin slices of Abondance. Rub some garlic (although some prefer this without) into small dishes (often called Berthouds) and a pinch of nutmeg or pepper. Then add the cheese.

Wet with a glass of Madeira or white wine, and bake for 10 minutes in the oven at 160°C/320°F. Serve like fondue, dipping squares of thick bread into the cheese, and have some new boiled potatoes on the side.

A second milking: Reblochon cheese

A few mountain ranges to the North, near the picturesque lakeside town of Annecy, the village of Thônes (pronounced Tone) is home to the Coopérative du Reblochon.

This uncooked Alpine semi-soft cheese is larger than Camembert but smaller than a wheel of Brie, and about the thickness of a roll of masking tape (but a lot better tasting!) It is the quintessential Alpine cheese.

Reblochon, just two weeks old by ngev via CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Reblochon, just two weeks old by ngev via CC BY-NC-SA 2.0Reblochon was the first alpine cheese to receive its AOC, back in 1958, but it actually dates back to the Middle Ages when the tax collector based his tax assessment on the number of pots of milk a farmer produced. The mountain herdsmen would produce a first milking, pay the tax, and when the collectors had gone away, finish the milking – hence the word ‘re-blocher’ (this means ‘to pinch a cow’s udder again’).

In other words, the cow is milked twice. Reblochon is made from this still-warm second milking. A real Reblochon comes from milk from a single farm – no mixing with neighbors!

Try my easy recipe for tartiflette – in winter this delicious potato and cheese gratin is one of my favorites.

Don’t be fooled, though: tartiflette may be typical of the Savoie region, but it is recent. It was only invented in the 1980s by Reblochon producers to increase cheese sales!

These days, tartiflette is one of the most popular dishes around, especially after a hard day’s skiing or snowboarding, and has done much to raise the popularity of Reblochon.

Roussette or Mondeuse are the wines of preference for this cheese.

Easy Tartiflette: The Perfect French Alpine Cheese Dish

The season's first tartiflette usually signals the arrival of winter. It's a great convivial dish, and like fondue and raclette, fun to share with friends.

Prep Time: 30 minutes

Cook time: 20 minutes

Yield: 4 portions

Ingredients

- 1 kg/2.2 lb potatoes

- 1 Reblochon cheese or similar

- 200g/half a pound of bacon (cut into small squares)

- 1 glass white wine

- a few shallots or an onion or two

- 20 cl/7 oz fresh cream

- salt and pepper

Instructions

- Boil the potatoes still in their skins. When they begin to get tender, run them under cold water to stop the cooking.

- Preheat the oven to 350°F/180°C.

- Peel potatoes while still hot and slice into thick coins.

- Melt your bacon in a frying pan, and add the shallots or onion.

- Remove the fat and add the white wine. Cook until the wine nearly evaporates.

- Mix with the potatoes.

- Cut the Reblochon into two half-moons, and cut again across the flesh, lengthwise, so you now have four pieces. Place the pieces, rind up, on top of the potatoes and bake until the cheese is melted. Conversely, cut into thick strips.

- Cook until the cheese is golden brown.

If you can't find Reblochon where you live, substitutes suitable for tartiflette include Fontina, Port Salut, Taleggio or Raclette cheese.

Accompany with any of the white fruity wines of the Savoie or drier whites such as Alsace or Sancerre. Light reds such as Beaujolais (Morgon, Juliénas) will also go well with tartiflette. If you don't drink, have a tea. Water will bloat you and you'll feel like you've eaten a cannonball.

You might also like...

Emmental cheese: Oh so famous!

Perhaps one of the best-known Alpine cheeses is Emmental, often confused with Gruyère, which it resembles. Like other Savoyard cheeses, its production is artisanal, limited to a small area with high-quality products.

It’s easy to tell apart from the others – it is far thicker in the middle than on the edges, and has holes the size of walnuts like the proverbial cheese traditionally associated with cartoon characters like Tom and Jerry.

French Emmental cheese by diluvienne / CC BY-NC 2.0

French Emmental cheese by diluvienne / CC BY-NC 2.0Emmental came into its own in the 19th century and because of its good reputation was more expensive than similar cheeses. By 1908 there were more than 400 Emmental producers in Savoie, many of whom are still around today.

This cheese travels well, which helps with marketing – early on, it was exported from the mountains and soon made its way along the far-away plains and beyond.

Emmental is France’s largest cheese, at 80 cm (more than two feet) across and weighing more than 60 kilos (130 lb). It is also France’s most popular: 94% of all French eat it regularly, and more Emmental is produced in France than even Camembert (which is to the French what Cheddar is to the English-speaking world).

For wine pairings, try a Crépy, Roussette or Crémant de Savoie.

Traditional Cheese Fondue

A wonderful cheese fondue recipe comes to us from professional Emmental producers.

Pour a glass of dry white wine and a crushed clove of garlic into a fondue pot. Heat gently until it foams but don’t let it boil. Add 800 grams (30 oz) of roughly grated Emmental. Stir with a wooden spoon in a figure 8 until cheese melts completely. Add a spoonful of Dijon or other French type mustard and a dash of pepper, cinnamon and nutmeg (go very easy on these last two, a pinch only!)

Bring the pot to the table (put something under it) and add a small measure of kirsch or similar alcohol.

To eat, dip squares of French bread, crust included, into the mixture with a special long fork that comes with the fondue set. And don’t forget to keep the flame alive – otherwise you’ll end up with a congealed lump. Time to dust off that cheese fondue set and try this recipe!

A classic cheese fondue

A classic cheese fondueCheese fondue comes from the identical French word that means melted. Most food historians agree that it originated in the Swiss Alps, slowly making its way to France and other neighbors (and over the mountains).

The term ‘fondue’ seems to have been coined by Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, a native of Belley, a small town just down the road from where I live in eastern France. He also coined the phrase “Tell me what you eat and I will tell you what you are,” and one of his most noted books, The Physiology of Taste, remains a culinary bible in France. Of course he also gives his name to a (non-Alpine) cheese so creamy and rich it is almost sinful to eat, the Brillat-Savarin.

Cheese fondue became highly popular beyond the Alps in the 1970s and is a mainstay of ski resorts and mountain chalets and cafés. And yes, it's time to pull out that set!

Here are your Emmental producers.

Tome vs Tomme

There are actually two cheeses with a near-identical spelling, the Tome des Bauges, which has only one ‘m’ and comes from the Bauges Mountains just behind Chambéry, and the Tomme de Savoie, a much older more traditional cheese.

Both are excellent and have their own qualities, of course.

The Tomme de Savoie has been around longer than other Alpine cheeses and has been much imitated. To make imitation harder, producers now stamp the word ‘Savoie’ in large capital letters around the edge of the cheese. And good news for those watching their weight – ‘skim’ Tomme with 20% fat is also available (but frankly, I find it rather tasteless).

Here's where you can find the Tomme de Savoie and Tome des Beauges.

All Alpine cheeses are easy to find in my local supermarkets

All Alpine cheeses are easy to find in my local supermarkets A delicious Tomme de Savoie by Coyau / CC BY-SA 3.0

A delicious Tomme de Savoie by Coyau / CC BY-SA 3.0Tomme and Ham Stir Fry

Peel and slice 800 g/1 lb 12 oz of potatoes into slices and then wash and dry them. Chop an onion. Remove the crust from 350 grams/12 oz of Tomme and slice the cheese. Heat some oil and butter in a large frying pan. Brown the potatoes in oil or butter and then and reduce the heat. Add the onion, and cook slowly for 20 minutes, stirring often. Add salt, pepper and a pinch of nutmeg. When the potatoes are golden, add the cheese. Cover and allow the cheese to melt at low temperature. Add 150 grams/5 oz of smoked ham. Cover and cook for a few minutes. Serve piping hot, accompanied by a green salad (with a garlicky dressing). A light white Savoie wine is perfect with this dish.

The fact that the Tome des Bauges is spelled with a single 'M' is a practical decision to differentiate it from the Tomme. They may have the same word root, but they are different cheeses and produced in different parts of the Alps. The Tome, of course, is made in the Bauges Mountains.

Both cheeses are somewhat similar.

Both are made from unpasteurised milk and are uncooked, pressed cheeses. They are also the same circumference, although the Tomme is a little thicker. Both have grey rinds, and the Tomme takes more time to mature (1-3 months) than the Tome (from 5-8 weeks). The Tome also has a higher fat content.

With a Tome des Bauges, try drinking a Jacquère, Roussette or Mondeuse and with a Tomme de Savoie, try a Gamay rosé, or again, a Roussette or Mondeuse.

There is such a thing as Raclette cheese

Most of us think of raclette as a dish, sumptuous squares of thick cheese set on a little tray and melted under a grill, to eat with potatoes and pickles.

It is that. But it is also one of the eight recognized Alpine cheeses with which you prepare a raclette.

The wheel is about 40cm in diameter and 10cm high, and weighs about 6kg. When heated, it melts beautifully, hence its use for raclette. And it is very fatty!

As soon as autumn rolls around, the shops are bursting with this cheese, a favourite meal because it is so easy to make: cut, melt, eat.

And it's been the same since the Middle Ages. When herders went to the mountains with their cattle, they would take half a wheel of cheese and melt it by the fire. They would then scrape, or 'racler', the melted cheese with a piece of bread or potatoes, hence the name Raclette.

To go with your Raclette, try a Roussette or white Chautagne.

Here are your producers of Raclette cheese.

With a crunchy salad: Chevrotin goat cheese

For those who prefer goat’s cheese, the Chevrotin, or ‘little goat’, is Reblochon’s little brother. This cheese has a particularly distinctive fresh taste because of the high rocky soil on which the goats graze.

Rather than a uniform recipe, each farmer makes Chevrotin by hand with his own recipe from raw goat's milk, and has done so since the 17th century.

A Chevrotin is best kept wrapped in the vegetable section of your fridge, in a sealed plastic container (but don’t forget to remove it from the fridge a couple of hours before eating). If you want it to mature, leave it out for a few days under a cheese bell or between two plates.

Eat it in a salad, at the end of a meal with dried fruit, or with dark or nut bread (pain aux noix), now available in most French boulangeries, accompanied by a smooth Savoie wine – the semi-sparkling Seyssel (from my own village) will do nicely, as will a Mondeuse or any Roussette from the Alps.

This is where you'll find ChevrotinThe perfect alpine cheese platter

There are certain rules (they're pretty flexible so don't panic) around setting up a cheese board, and an Alpine cheese platter is no different.

What goes on the cheese board

The basic cheese board usually has a minimum of three cheeses – a combination of a hard cheese, a soft cheese, an aged cheese, a blue cheese. For an alpine board, that could be a comté, a chevrotin and a bleu, or Alpine blue cheese. That could be a Bleu de Bonneval or a Persillé Aravis or Tignes, for example. These may not be one of the eight, but they are perfect nonetheless.

Or, it could be an Emmental, some Reblochon, and a blue or fresh goat's cheese.

Or... you can go by season!

Your best French cheese board ideas by season

- In springtime, the grass is green and full of flowers, the perfect season to include Reblochon and Chevrotin on your platter.

- In summer, take advantage of cheeses that have been maturing since last year or that mature quickly – a good time for Beaufort, Chevrotin and Reblochon.

- In autumn and winter, it's time for Tomme , Tome and all the hard cheeses – Emmental, Raclette, Abondance...

Mixing up your platter

The beauty of a cheese board is to mix it up, not just cheeses but also colours and shapes. This is a good time to let your inner artist run wild!

Here are some of the foods you can add to your cheese board, in varying quantities and proportions:something sweet, like fig jam, honey or dried fruit

- something crunchy, like walnuts or candied nuts

- something meaty and salty, charcuterie like air-dried beef or dried ham

- several kinds of bread or biscuits

- something tart, like pickles

- something fresh, like grapes or apple slices

- garnish, like sprigs of rosemary or thyme

How to eat your way through it

This may be obvious but we forget: start with the mildest-tasting cheese and work your way up in intensity. It's the same with any food. If you start with a hot curry and then eat steamed fish, you won't taste the fish...

With Savoie cheeses, you might start with the lighter Emmental, Beaufort and Tommes. Work your way through the Reblochon and the stronger Abondance. And cap it off with the goat's milk Chevrotin.

Here are some items to help you assemble your perfect alpine platter

- Serve up your cheese portions on these elegant slate charcuterie boards

- For a larger cheese board, have a look at this lovely acacia board

- Surprise your guests with these stylish stainless steel cheese knives

- In this book, a French master fromager unveils the secrets of fromage

The Alpine Cheese Route: Take it for a day!

Much like a Wine Route or Silk Route, cheese in the Alpine region of France has its own route (one of many cheese routes across France). It's called the Route des Fromages de Savoie, or the Savoy Cheese Route.

It's not a formal route as such but a collection of stops throughout the region, a network of 74 cheese makers who have agreed to abide by certain standards common to them all.

This is a list of the region's cheese producers (the site is in French) divided geographically. Just grab a map of the region and hit the road!

How to Pack a Real French Picnic

There is rarely a road in France at lunchtime without its picnickers. Out come the folding tables and chairs, the tablecloth, plastic dishes and the bottle of wine. A proper Alpine picnic would include the following: cheese, of course; bread and something to drink; pickles or something sweet to add to the cheese; grapes and nuts. And don't forget your dishes and cutlery, a blanket and a tablecloth. Or take along one of those lovely traditional picnic baskets.

A note of caution: French police do not joke about drinking and driving so make sure one of your drivers doesn't touch that wine. You'll need your wits about you – it's hard enough to navigate French roads and drivers while sober. (These driving tips should help you on those French roads.)

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!

Pin this story and save for later!