Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Destinations ›

- Southern France ›

- Legends of the Luberon

The Mysterious French Legends of the Luberon, Provence

Published 12 March 2021 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

Everywhere I go in France, I stumble upon stories and tales and legends. As I visited the Luberon, I researched its wonderful hilltop villages and of course, found plenty of intriguing tales...

There's something about the Luberon... This land of sunshine and smiles spreads its essence through all the senses: the beauty of its hilltop villages (several of which are listed among the most beautiful villages of France), the scent of lavender and taste of fruits and olives, the sounds of rustling leaves and chirping cicadas.

It has attracted artists for many years, its landscape, charm and history a fountain of inspiration for writers and painters.

With such a background, it's no wonder this land has given birth to imaginative French legends and stories that explain its almost painful beauty.

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

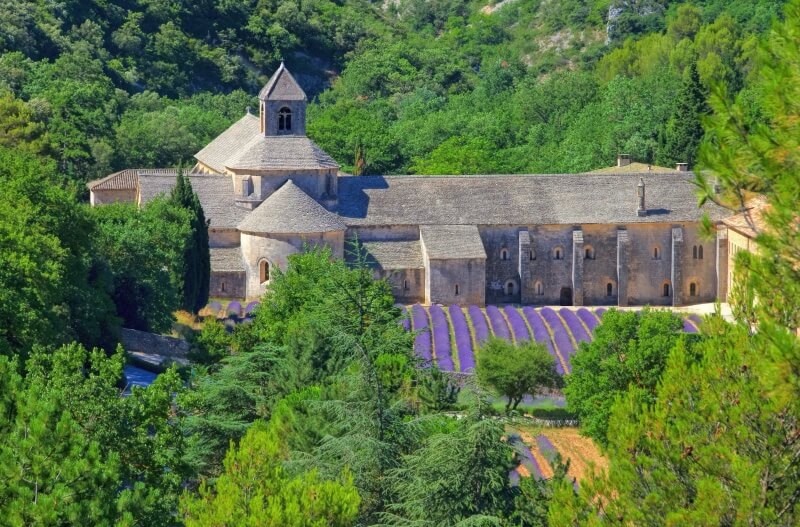

Lush lavender in summer in the Luberon

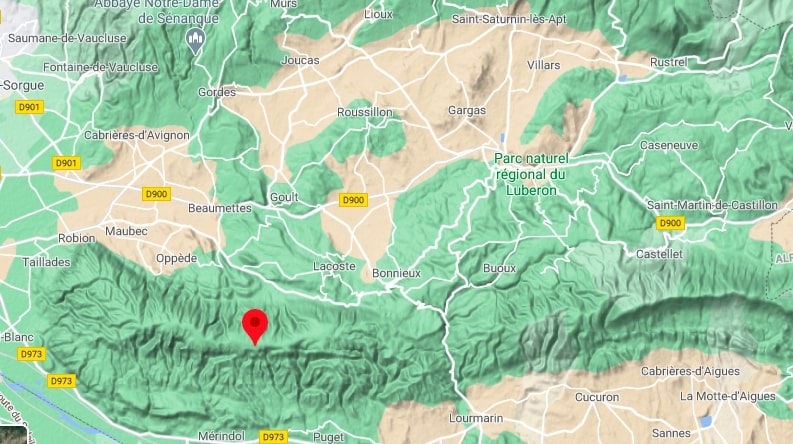

Lush lavender in summer in the Luberon Map of the Luberon, Provence - click here to enlarge

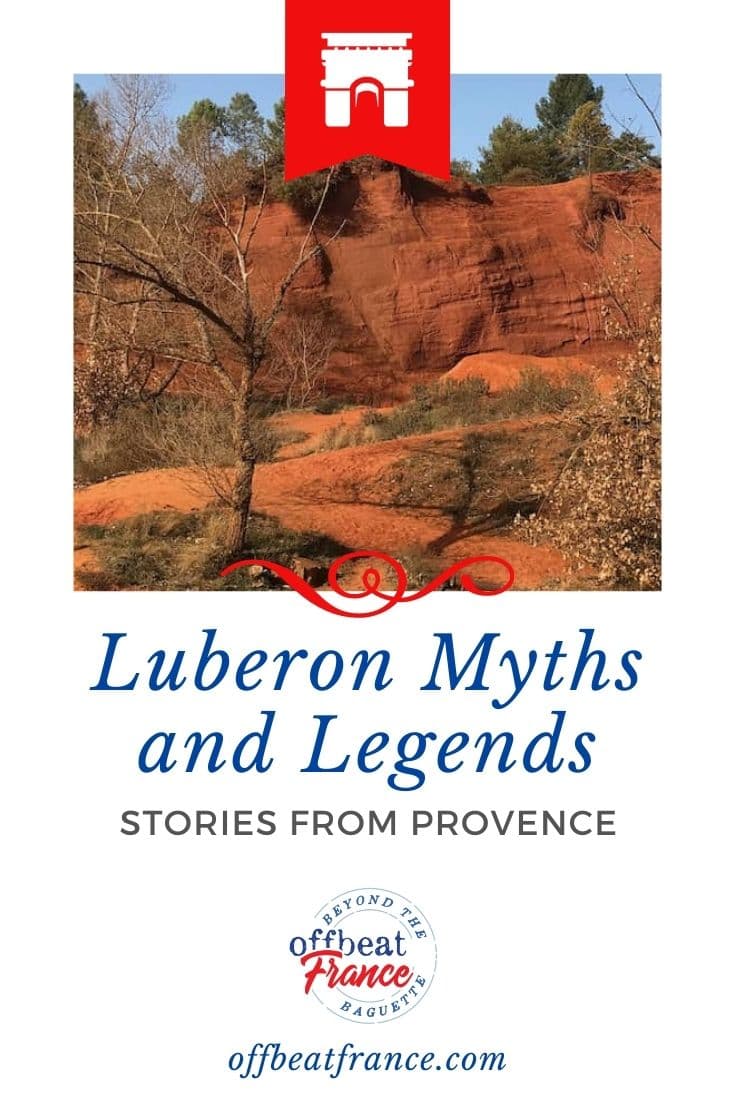

Map of the Luberon, Provence - click here to enlargeThe red earth of Roussillon

One of the most popular villages of the Luberon is Roussillon, with its ochre hills and burnt red houses. You can't miss the hills: they are in the center of the village, their cliff edges facing you like explosions of sunshine.

One of the most popular French legends of the Luberon

One of the most popular French legends of the LuberonBut how did the hills become deep rust? Was it really the ochre, or is there another story behind it?

Well, both. Yes, the natural cause of the colour is indeed the ochre, the world's oldest known natural pigment.

But we can dig just a little deeper and come up with another tale of origin.

Among the more dramatic medieval stories and legends of France is that of Lady Sermonde and her terrifying husband Raymond d'Avignon. The fair lady was often left alone for days by her absent husband, gone hunting, so it would come as no surprise that she befriended Guillaume, a young (and available) troubadour. Eventually, the two fell in love and things happened.

Of course someone told the husband and, furious, he invited Guillaume to go hunting with him. He promptly stabbed him in the back and decapitated the unsuspecting troubadour.

Upon returning to the castle, he asked his cook to prepare a meal for his wife (you know what's coming, right?) and once she had finished her delicious dinner, he revealed her stew had been prepared with her lover's heart.

The Lady Sermonde, horrified and heartbroken, ran outside and threw herself off the cliff, her blood splashing red all over the hills, never to be erased.

The tale of Lady Sermonde is the most popular legend of Roussillon, but there are others, though none as popular.

Like the tale of the Titans, who wanted to invade Provence but were prevented from doing so by the local inhabitants. So they hid in a cave and built a giant cannon, which spewed forth its anger and its flames, all over Roussillon hill. And the hill stayed red...

The siege of Ménerbes

Not far from Roussillon is another much-loved hilltop village, Ménerbes. This tiny perched fortress was always a favourite of artists but it achieved particular international renown when Peter Mayle wrote A Year in Provence, which foreshadowed the arrival of thousands of mostly British tourists.

Ménerbes is an ancient village, its land inhabited since the Palaeolithic and its name reminiscent of Minerva, Roman goddess of the arts and eventually, of war. The village lies on the Via Domitia, which linked Rome to southern Spain and you can still see the Via Domitia signs up and down the main road of the Luberon.

As for Minerva and her protection of the arts, Ménerbes can boast of that same tradition today, as a haven for artists from all over – Peter Mayle, perhaps, but also Picasso (and Dora Maar, an artist and photographer who became his lover).

Ménerbes is known for a 15-month siege during the Wars of Religion: the Huguenots captured the town and resisted the Catholic onslaught, despite being outnumbered by 10 to 1. Eventually, they capitulated with honour and the village returned to Catholic rule as part of the Papal lands, only to be annexed (as were all Papal lands) during the French Revolution.

Despite the village's placid appearance, a dark French legend haunts its environs, if an interview with the village historian of Ménerbes (in French) is to be believed.

It's a story about a cave and dates back to the 100 Years' War. A violent highwayman, Pierre de la Vache, and his criminal acolytes, escaping justice, took refuge in a cave. Pierre's brother, a more honest sort, turned him into the authorities but when lawmakers arrived to arrest him, Pierre realized his brother's treachery. Grabbing him by the arm, Pierre threw him over the cliff, and jumped off after him. Both died side by side, the rest of the gang was arrested, and tranquility returned to Ménerbes.

Except that... come nighttime, the two men's ghosts are often spotted in the village. Worse, they're believed to hover near the cave – and push unsuspecting hikers to their deaths.

Today, the village's watchtowers no longer guard against enemies but against hordes of tourists which invade every season. The citadel was eventually bought by Picasso and became the village's emblem.

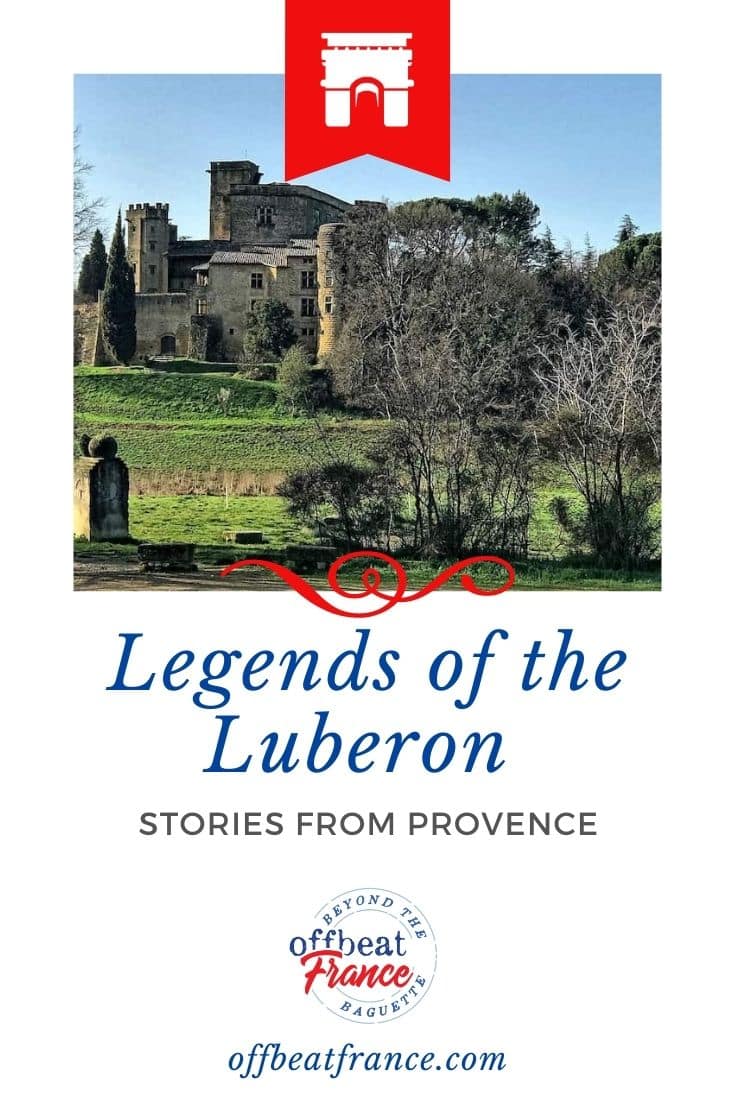

The haunted castle of Lourmarin

At the southern end of the Luberon is another much-loved village, Lourmarin, which appears nearly magically as you round the last bend of the mountain road linking this to the Grand Luberon in the north.

The first thing you see is a Renaissance castle, built on the foundations of a 12th century fortress.

But all was not always peaceful here. In 1545, in the lead-up to the Wars of Religion, the town was torched because of its predominantly Protestant population.

The castle fell into disrepair, with successive owners caring more about squeezing a profit from the land than rebuilding the chateau.

Romani travelers eventually squatted the property, using it as a way station on their way south to the annual May Romani gatherings in the Camargue.

Strange scratchings appeared on the walls, possibly in the Armenian language, along with drawings of a sailboat with people on board, all surrounded by a cross, a swastika, five-point stars and the word "Armeny". It seems as though a family of that name did indeed exist... in Marseille, having settled there for centuries. Perhaps they traveled through Lourmarin one day, stopped there, and left a bit of graffiti?

Next to the drawing, over a door, you can find the following: "Drink and then go, 1513". This might have been a directive to the Romani – have a drink at the castle fountain but don't hang around!

Then in 1920, a wealthy industrialist from Lyon bought the building and expelled the travelers. Angry at having to leave, they placed a curse on him − and on anyone linked to the chateau.

Many people involved in restoring the castle would henceforth meet an untimely end, whether by suicide or road accidents.

The most notorious is the fate that befell the writer Albert Camus. He had just ceded some of his royalties to the foundation in charge of the chateau when, the very next day, he was killed in a road accident. In all, 13 people in some way related to the chateau would die between 1925 and 1960.

It is difficult to imagine such a lovely venue meting out such tragic outcomes...

Fontaine de Vaucluse and the secret of the source

Fontaine de Vaucluse is a small town at the end of a road to nowhere, jutting into a gorge along which rushes a river whose origins are unknown. It simply bursts out of the mountain, almost magically, ready born.

The roiling waters of the Sorgue

The roiling waters of the SorgueThe emerald Sorgue River gushes from the mountain with a strength nearly unequalled in Europe. Scientists, who have so far been unable to pinpoint the river's source, believe it is the culmination of a massive network of underground rivers whose pressure pushes them out of the ground.

Of course, this mystery lends itself to several stories, including one of the more popular legends in France...

One of these is about a village fiddler called Basile, who, on a hot day, fell asleep in the shade on the road to Fontaine de Vaucluse. A beautiful nymph appeared, fair as the sky, who took his hand and led him to the water.

The river parted and they walked down, a crystal wall of water cascading down either side. After a long underground journey they emerged into a field covered in heavenly flowers. The nymph and the fiddler stopped in front of seven huge diamonds.

She lifted one, and out spurted a fountain of water.

"This is my secret," she said, "the source of which I am the guardian. To make it rise, I remove a diamond at a time. When I get to the seventh, the water reaches the fig tree, once a year." And she disappeared, jolting Basile awake.

No one knows what happened to the nymph but the Sorgue remains, a fantastical and magical river bursting out of the ground, no one knows from where.

In another, more gruesome story, lost in the folds of time, a terrifying creature, a coulobre − a type of winged half-salamander half-serpent − once lived in the river's source, looking for a mate. One day it found a dragon and they coupled, giving birth to a black salamander with gold spots. But the dragon ran away, abandoning the coulobre to her fate (a custom still common today).

The coulobre, desperate to find another mate to help raise her offspring, hid in the spring, her hatred distorting her already unattractive features. She only emerged at night, terrifying the villagers.

One day, a hermit (or a bishop, depending on the story) named Véran came to the rescue. He waited for days and eventually, when the creature appeared, he fought it with his sword and made the sign of the cross. This gesture wounded the coulobre, who flew into the sky and crashed onto a mountain, near a village which to this day bears his name, Saint-Véran.

However dead the creature might be, at nightfall, it is said that young men occasionally disappear into the Sorgue's waters...

Forgotten for years, the legend resurfaced around the 15th century. In it, the Italian humanist poet, Petrarch, would have lived in this village and fallen in love with an aristocratic married woman, Laure. One night, while strolling along the river with Laure, Petrarch was attacked by the creature and they fought. He killed the coulobre who, in a final gesture of spite, breathed its foul breath upon Laure, who soon died of the plague.

Long ago, water wheels were built along the Sorgue and here, in Fontaine de Vaucluse, to help direct waters for agriculture

Long ago, water wheels were built along the Sorgue and here, in Fontaine de Vaucluse, to help direct waters for agricultureToday, Fontaine de Vaucluse honours the poet with a museum and plenty of art-themed exhibitions, not for his victory over the coulobre, but for his poetic accomplishments.

More French legends and myths: The story of lavender

What would Provence be like without lavender? It doesn't bear thinking...

Everywhere you go in the Luberon, you'll come across a field of lavender − and, not surprisingly, there may be a fairy involved.

Her name was Lavandula and she lived somewhere in Provence, flitting from place to place. Eventually, she decided it was time to settle down. She leafed through her sketchbook looking for the perfect place but, saddened by the arid scenes pictured on her pages, she began to cry big, violet tears, smearing her drawings. She tried to repair the damage by wiping the tears with her hands but that only made things worse − the tears spread even further across Provence's landscape.

To take our minds off the violet smudges, she drew a big blue sky and since then, lavender grows profusely across Provence, intertwined with the blue sky, like lovers in a sweet embrace.

The birth of the cicada, another French myth

Like lavender and olive trees, cicadas are part of the fabric of Provence... But how did they come to be?

It all started at the height of summer, when the angels came to spend their holiday in Provence (some things never change). When they arrived, they found no one; the fields, too, were empty and dry and the mountainous terrain arid... Upset with this situation, the angels wandered over to the church, where they found the priest asleep, enjoying his afternoon siesta.

The arid landscape of the Luberon

The arid landscape of the LuberonThey shook him awake and asked him why the land was abandoned.

"Because of the heat," explained the priest, "the people of Provence go to rest in the shade of olive and fig trees."

"So when does everyone work?" asked the angels.

"In the morning freshness, and late in the evening."

The angels, displeased with these answers, they went to heaven and told God, who sent down some new insects that would prevent them from having siestas in the middle of the day. Since then, cicadas have been loudly serenading the people of Provence at the height of summer days, dooming their siestas and keeping them awake with their powerful sound.

In the end, though, everyone got used to the cicadas' sound, the siestas resumed, and Provence even adopted the cicada as a symbol.

And so, Provence, the land of beauty and breeze and bountiful aromas, continues to pull us in and weave its magic.

But behind this smiling appearance lurks a darker edge, an element of the unknown, one that might make you shiver just a little. To experience it, you may just have to come here in person.

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!

You might also like...

Pin these and save for later!