Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Ze French ›

- Holidays & Traditions ›

- New Year's Traditions

6 French New Year Traditions That Are Centuries Old

Published 28 December 2024 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

France has a wealth of New Year traditions, from pagan to Christian and everything in-between. Here are a few of the more unusual ones, with stories and legends that show how we welcome in the New Year – or used to − and how some of these remain today.

New Year celebrations can be simple things − friends and family, a bit of champagne, next year’s resolutions… but we don’t realize that many of these seemingly anodyne habits may have their roots far in the past.

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

1. What’s in a date? How 1 January became the first day of the year

We owe the first day of the year to Julius Caesar.

In 46 BCE, he introduced the Julian calendar, which standardized the length of months and established January 1 as the start of the New Year.

January is named after Janus, the Roman god of beginnings and transitions. Traditionally, he is shown with two faces looking in opposite directions − he can look both forward into the future and backward into the past, not a bad viewpoint for the start of a New Year.

To celebrate the arrival of the New Year, the Romans would hold sacrifices and make temple offerings, but 1 January wouldn’t really be considered the first day of the year permanently. Not yet.

THE IMPORTANCE OF DATES

The Julian calendar, introduced by Julius Caesar in 46 BCE, would be widely used for over 1600 years. But it wasn't perfect: it miscalculated the solar year’s length by about 11 minutes, causing dates to drift over centuries.

To correct this, Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian calendar in 1582, realigning the calendar with the solar year. This reform would gradually be adopted by various countries and eventually become the norm.

The beginning of the year kept hopping around.

Under the Merovingians, who ruled France from the 6th-8th century, 1 March would be the year’s start, while their successors, the Carolingians, would celebrate it on 25 December, the presumed day of Christ’s birth − and the day Charlemagne was crowned. Sometimes, the New Year might also be celebrated around Easter.

For 1 January to become the “permanent” start of the year, we would have to wait until 1564. That’s when King Charles IX issued the Edict of Roussillon, which established 1 January permanently (with a brief interruption, as we'll see in a moment) as the start of the year in France.

Now, about that interruption... things all got messy with the French Revolution.

In 1793, the French Republican Calendar overhauled the system entirely, shifting the New Year to the first day of something called Vendémiaire (around September 22-24). France was trying to de-Christianize and rationalize French society, and changing the calendar to reflect revolutionary priorities was part of that effort.

It would be confusing and thankfully short-lived. In 1806, Napoleon re-established the Gregorian year, still in use today.

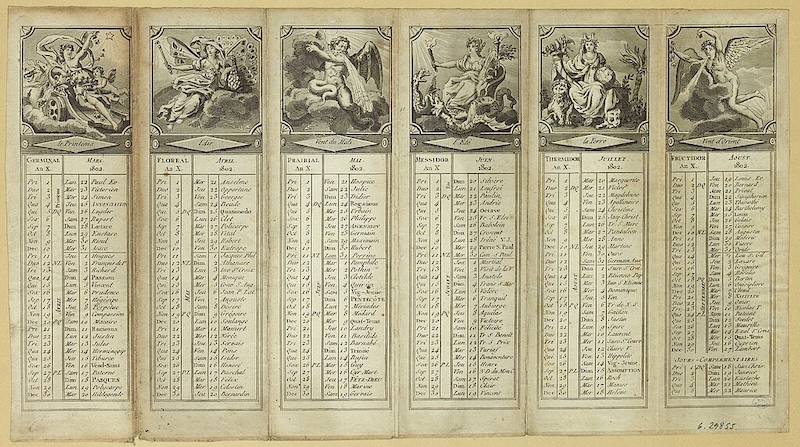

The new Republican Calendar introduced by the French Revolution, alongside the Gregorian Calendar to help find equivalent dates

The new Republican Calendar introduced by the French Revolution, alongside the Gregorian Calendar to help find equivalent dates2. One had to please the king

During the Ancien Régime, when royals ruled France, one had to keep the King happy.

Often this was done by giving him étrennes des rois, or gifts to the king, basically to curry favor or demonstrate loyalty or to ask for favors. These could be simple gifts, just tokens, really, or they could be lavish jewels or intricate mechanical devices.

Usually, the higher the rank, the greater the gift.

Louis XVI receiving his gifts - his etrennes - on New Year’s in 1790, two years before the monarchy was abolished

Louis XVI receiving his gifts - his etrennes - on New Year’s in 1790, two years before the monarchy was abolishedThis gift-giving extended right down the social hierarchy, with nobles and commoners often falling over one another to impress and compete.

Come New Year, this was only part of the protocol. The king also held special audiences to receive dignitaries, ambassadors, and members of the court, who presented their respects. This set the tone for the New Year, but also provided an opportunity to show everyone just who was in charge.

Today, we have parties, not receptions, but we still give out the étrennes – not to the king anymore, but to the postie, the fire brigade and gendarmes (when they come by selling their calendars), the concierge, the guy who helps you at the déchetterie (the tip, or dump, depending on where you're from), and countless others who receive money or a bottle of wine for services rendered during the yeat.

3. Eat, drink and be merry

This being France, a number of traditions are bound to involve eating and drinking.

Like sabrage, the art of slicing off a champagne cork with a saber (which you may have seen enacted with dire consequences in season 2 of Emily in Paris). This can be traced back to Napoleon’s light cavalry, whose hussars celebrated victories by flamboyantly slicing open bottles of champagne with their weapons.

As an aside, while his links to sabrage are well documented, Napoleon is also widely quoted as saying, “In victory, you deserve Champagne; in defeat, you need it.”

Unfortunately, there’s no evidence of this and the closest we can get is a quote by Winston Churchill, which goes like this: “I could not live without Champagne. In victory I deserve it, in defeat I need it.”

Concentration is key to sabrage, the art of slicing a cork off a champagne bottle with a saber

Concentration is key to sabrage, the art of slicing a cork off a champagne bottle with a saberOver time, sabrage became associated with festive occasions, including New Year’s celebrations, where it added a theatrical tweak to the festivities.

Today, sabrage remains a ceremonial practice, adding a touch of historical grandeur and excitement to celebrations − you can hire someone to demonstrate this at your party, or you can actually learn to do it yourself.

But tradition is not only about champagne...

In Burgundy, a special bread (pain de l’an neuf) baked for New Year’s may be blessed for the occasion, a blend of religious and folk beliefs. The cross which is sometimes drawn on the bread symbolizes protection and blessings for the household.

In Provence, placing a coin under the plate during the New Year’s meal is a tradition intended to bring prosperity, reflecting a blend of religious and folk beliefs.

And there are so many others...

4. Les revenants

At midnight on New Year’s Eve, you’ll hear church bells ring.

In some parts of France, like Normandy, these were traditionally believed to ward off evil spirits, marking the transition from the old year to the new.

Bells have often been used to signal the change from the old to the new year. Photo ©Farz brujunet, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Bells have often been used to signal the change from the old to the new year. Photo ©Farz brujunet, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia CommonsThe bells are associated with folklore about phantom processions (les revenants) − basically a cavalcade of ghosts or devils led by a mysterious figure − a supernatural event in which the dead or otherworldly beings cross the night sky.

Communities would gather in anticipation, counting down the final seconds together as the bells rang, marking the transition from the old year to the new − a bit like the 12 grapes eaten in Spain as the bells toll the New Year.

The message is clear: acknowledge and respect the spirits of the departed, and remember that this is a time of renewal.

5. Divination with the Celts

In Brittany, a region with strong Celtic heritage, New Year’s Eve was traditionally seen as a time for divination.

Practices like interpreting candle wax drippings (ceromancy) or molten lead patterns (molybdomancy) were used to predict the future.

To interpret candle wax drippings, participants would light a candle and let the molten wax drip into a bowl of cold water. They would then study the shapes made by the solidifying wax and use these to glean insights into the future: a heart shape might predict love, while a circle could signify continuity or an upcoming journey.

Another popular divination method was molybdomancy: just as was done with the candles, small amounts of lead were melted and quickly poured into cold water. The resulting shapes were interpreted to forecast events in the coming year. This was not an easy practice and required careful handling because of the high temperatures involved.

Molybdomancy is the practice of melting lead and pouring it into cold water, using the shapes to predict the future

Molybdomancy is the practice of melting lead and pouring it into cold water, using the shapes to predict the futureTypically, these rituals took place during the liminal time of New Year’s Eve, a period considered to be “between the years,” when the veil between the physical and spiritual worlds was believed to be thinner.

These days, examples of these practices are mostly relegated to museums but they are often still part of the New Year traditions. That said, the renewed interest in many of the more occult practices means you’ll easily find books about these practices, and even DIY kits!

6. Kissing under the mistletoe

Kissing under the mistletoe is usually associated with Christmas, but it wasn’t always so. It was once a New Year’s custom until the Catholic Church moved to ban it because of its pagan connotations.

In France, it is still associated with the New Year. We kiss under the gui (pronounced GHEE) at midnight, to attract good luck in the coming year.

Historically, mistletoe was linked with pagan rituals and Druidic practices in regions like Brittany. The Druids revered mistletoe, especially when found on oak trees, believing it possessed mystical powers that could ward off evil spirits and bring prosperity. Only the druids were allowed to gather it.

Mistletoe was believed to be sacred and hold many powers

Mistletoe was believed to be sacred and hold many powersMistletoe was believed to hold many powers − as a cure for poison, and an aid to fertility. As far back as the Middle Ages, it was believed that lovers who kissed under the mistletoe could look forward to happiness, and to producing a long lineage.

These days, mistletoe is used as decoration during the holidays, hung above doors or at home, and is often considered a porte-bonheur, or good luck charm.

As I write this, the New Year is approaching and I must head off into the forest with my little serrated knife and step-up IKEA stool, hoping I can stretch to reach some of those lower branches…