Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Destinations ›

- Normandy ›

- Joan of Arc in Rouen

In The Footsteps Of Joan Of Arc In Rouen

Published 28 March 2024 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

Joan of Arc was only 19 when she was tried and burned at the stake in Rouen in 1431. Although nearly six centuries have passed, the city continues to pay its respects to the “Maid of Orleans”. Here are six major city sites that honor Joan.

Heroine, saint, martyr?

When a young lady from Lorraine convinced a local nobleman to introduce her to the future king of France, Charles VII, she had no way of knowing she would take up arms against the enemy, face resounding triumph, be betrayed and tried for heresy, face an agonizing death by being burned at the stake, and eventually become the patron saint of France.

What a strange fate for the illiterate (she could only sign her name) daughter of a tenant farmer from a rural corner of Lorraine…

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

Trying to understand Joan of Arc’s capture and death requires a bit of context – a short historical diversion if you will (but if you already know her story and have no need to read it again, head straight to this section to follow in her footsteps, one of the indispensable things to do in Rouen).

The inevitable historical background

Joan of Arc, as we know, was a young woman from Lorraine in northeastern France who heard sacred voices compelling her to “save France” and get Charles VII crowned as king. Through a barrel of defeats and victories, she found herself at the head of a French army, slowly pushing back the English.

But why? How did this happen?

Remember, we were in the latter part of the Hundred Years’ War, which pitted French against English in a fight for the French throne. The English, with superior tactics and weapons, had advanced into France and hoped to claim it for themselves.

And there was a third party involved: Burgundy, an independent duchy. The Burgundians, initially pro-French, switched sides when their duke, Jean Sans Peur (Fearless John) was assassinated. They blamed the future king of France, and changed their alliance to England by signing the Treaty of Troyes with the English. The treaty disowned Charles and confirmed the English as heirs to the French throne.

Led by divine guidance (the voices) and after a multitude of adventures, Joan was able to convince the French pretender she should fight at the head of the French forces. She succeeded in unifying them against England and Burgundy, and eventually managed to get Charles crowned king of France.

The English were livid, so when she was thrown from her horse in Compiègne north of Paris and captured by the Burgundians, they sold her to England. If you’d like to know the whole story, Joan of Arc: A History is a great book with excellent background on 15th-century France.

Once captured, she was sold at auction, as was the custom with prisoners. Charles VII, by now negotiating a peace with Burgundy, didn’t lift a finger to save her. The English, on the other hand, were delighted to pay a huge sum (12,000 livres tournoi at the time) for her.

They wanted her tried by a religious court, which required an investigation and would thus provide the trial with legitimacy. They were lucky – they found a willing judge in Pierre Cauchon, Bishop of Beauvais, who was pro-Burgundian and living in Rouen. Seven months after her capture, Joan would be brought to Rouen, on 23 December 1430.

Her trial opened on 21 February 1431, and despite holding her own, she was found guilty of heresy, witchcraft, and dressing like man. She was given a short reprieve when she was pushed into confessing, but soon was sentenced to be burned alive. Joan of Arc was executed on 30 May 1431, a sentence that would be overturned in a re-trial 25 years later (and 25 years too late).

Joan of Arc at the stake, as illustrated on a medieval manuscript by Martial d'Auvergne, The Vigils of Charles VII, courtesy BnF/Gallica

Joan of Arc at the stake, as illustrated on a medieval manuscript by Martial d'Auvergne, The Vigils of Charles VII, courtesy BnF/GallicaGranted, this is a very potted history of the life and death of Joan of Arc, and leaves out the many twists and turns of a story that is at times harder to believe than a novel. For an excellent book about the trial itself – historically accurate and using Joan’s own vivid words – read Joan of Arc: By Herself and Her Own Witnesses, written by Régine Pernoud.

Each momentous stage of Joan’s short life is marked in Rouen, and each step you take in this medieval city will remind you of the maid who brought both glory and death to it.

Following Joan of Arc in Rouen

Joan of Arc spent most of her life in other parts of France, but Rouen recalls one of the best-known events of her life: her death.

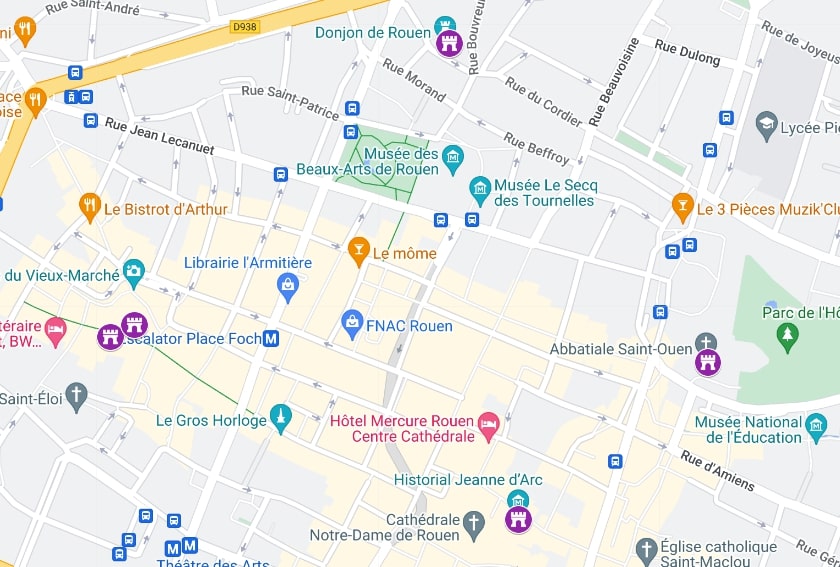

Follow this Joan of Arc Rouen map along the most important moments of her journey here, starting where the Rouen train station stands today.

1. The dungeon

Her arrival in Rouen begins at the dungeon, in the tower of a castle that no longer exists. The dungeon is now mostly closed to the public and hosts escape games, although you can occasionally get into its ground floor.

2. The Abbatiale Saint-Ouen

As Joan was accused and stood her ground, it was finally decided to scare her into confessing. She was brought to the cemetery of the Abbatiale Saint-Ouen, where a makeshift pyre had been set up. She was shown instruments of torture and promised leniency if she confessed.

Exhausted, she finally signed a document and agreed to change back into women’s clothes. Her death sentence was commuted to life, although we know that wouldn’t last long. A few days later, she reverted to men’s clothes (her women’s garments had apparently been stolen) and was promptly accused of relapse. Her death sentence was reinstated.

The Abbatiale would undoubtedly mark Joan, with its threats and menaces, so much in contrast with the abbey's Radiant Gothic (or Rayonnant) style.

Sadly much of it was under restoration when I visited, including its world-famous Cavaillé-Coll organ and plenty of statuary – but many of the 80 stained glass windows were perfectly visible.

3. The Jeanne d’Arc “Historial”

This unusual destination is located inside the Archbishop’s palace, where Joan of Arc’s fate was sealed – this is where her death sentence was handed down, but also where her retrial will take place.

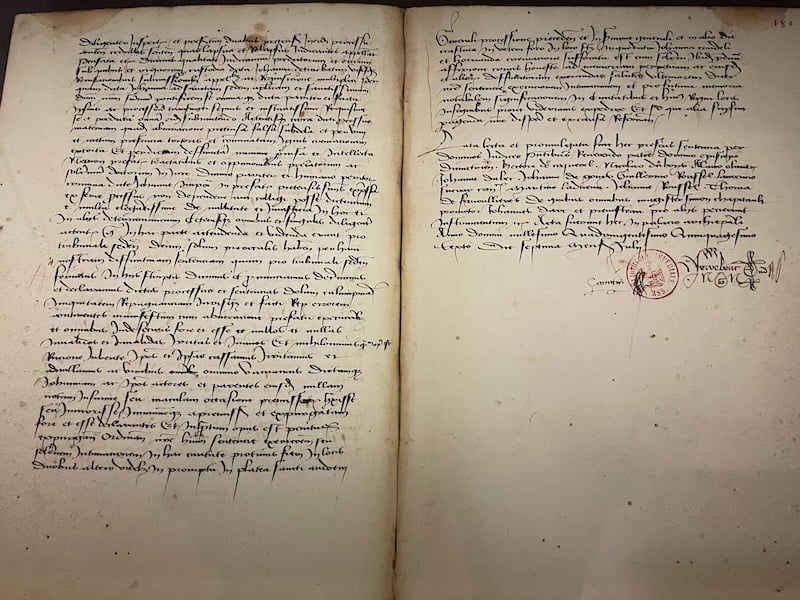

Today, it has been transformed into an interactive biography where a multitude of rooms succeed one another with multimedia exhibits that, in some cases, bring Joan’s story to life in a terrifying way. This is especially true of the various readings of her trial and retrial, whose original written documents you’ll also be able to see.

The “Historial”, as it’s called, traces her life story from young woman to heretic to saint over the centuries, culminating in several rooms that deal with the differing visions of Joan over the centuries and culminating in her use as a political symbol across the spectrum of French politics.

As you reach the end of the visit, don’t miss the Chapelle d’Aubigné, an uplifting spot with which to finish your visit.

4. The pyre

On 30 May 1431, the Maid of Orleans is burned to death on the Place du Vieux Marché, a major square that remains very much a marketplace, and a central social magnet filled with food stalls and restaurants, in stark contrast with its history.

For centuries, it was thought that her life had ended right behind this square, on the Place de la Pucelle, but no, it appears the market square is the correct destination. It’s hard to tell truth from fable but there are tales of La Couronne, which just might be France’s oldest inn, being filled with spectators watching the flames leap up. It faces the square and if true, they would have had a front-row seat.

The pyre was too tall, which prevented the executioner from strangling her before the flames reached her, ensuring she would have a horrible, excruciating death.

Today, the pyre’s location is marked by a cross, which is a national monument to Joan. A statue commemorates the dreadful date.

Once her execution was over, to prevent martyrdom, Joan’s ashes would be thrown into the Seine from the Pont Mathilde, built in 1160 and donated to the city by Empress Mathilde, William the Conqueror’s granddaughter. The bridge has disappeared, but it did last until the early 17th century.

5. The memorials

Some years ago, excavations on the square yielded the foundations of an old church, Saint-Sauveur. It is said that while on the pyre, Joan requested a cross and was brought one from this church. It is also where Pierre Corneille, the 17th-century French playwright, was baptized. (His house is around the corner and still stands.)

The pyre and old churches have been replaced by a soaring creation designed by prolific architect Louis Arretche. The Eglise Sainte-Jeanne-d’Arc shocks at first sight, a modern flight of fancy set within a ring of half-timbered medieval buildings.

A bit like the Louvre pyramid or the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the contrast was initially controversial is now much-loved by many (not all!) Rouennais. It was deemed important enough to be inaugurated in 1979 by the then president of France, Valéry Giscard-d’Estaing.

The concrete exterior is topped by a slate roof, an abstract creation that looks like a sail, or a fin, or the bottom of a boat. The interior, in contrast, is luminous and minimalist, ringed by a series of 13 Renaissance stained glass windows salvaged from the 1944 bombing of Saint-Vincent church next door.

The combination of church, cross and statue stand as memorials to Joan of Arc and her fate in Rouen.

IF YOU'D LIKE TO LEARN MORE ABOUT JOAN OF ARC

Have a look at these two excellent books:

- Joan of Arc: By Herself and Her Witnesses by Régine Pernoud

- Joan of Arc: A History by Helen Castor

Joan of Arc’s legacy: beyond Rouen

Today, Joan is an icon and icons are often used for other purposes.

In her case, her name or image have been linked to art, the Catholic church, consumer goods and yes, politics.

She is resoundingly popular across France, and I’ve rarely seen a town or village that doesn’t have a statue, square or at least a street named after her.

In Rouen, you’ll find Joan of Arc on nearly every corner – the major landmarks, of course, but plenty of other reminders of her story, including a bakery, a liquor store, a clothes shop, a special pastry named after her, an organic food shop, even a fridge magnet powered by artificial intelligence that answers all your questions about her!

You’ll find books about her, comic strips, and such everyday objects as envelope openers and dishes. There’s hardly an item that hasn’t, at one time or another, been named after her.

Joan of Arc’s role in popular culture

For a period after her death, little was heard of Joan of Arc. She disappeared from history, returning towards the end of the 18th century, during the Enlightenment. Much research was taking place, and manuscripts about her life and trials were unearthed, reigniting interest.

Her life and death embodied courage and resilience, and an example of what can be accomplished through faith. For Rouen, she is a source of local pride, and her links with the city helped highlight her place in history and the city’s role in it. Each year, reenactments remind citizens and visitors of her legacy and keep her memory alive.

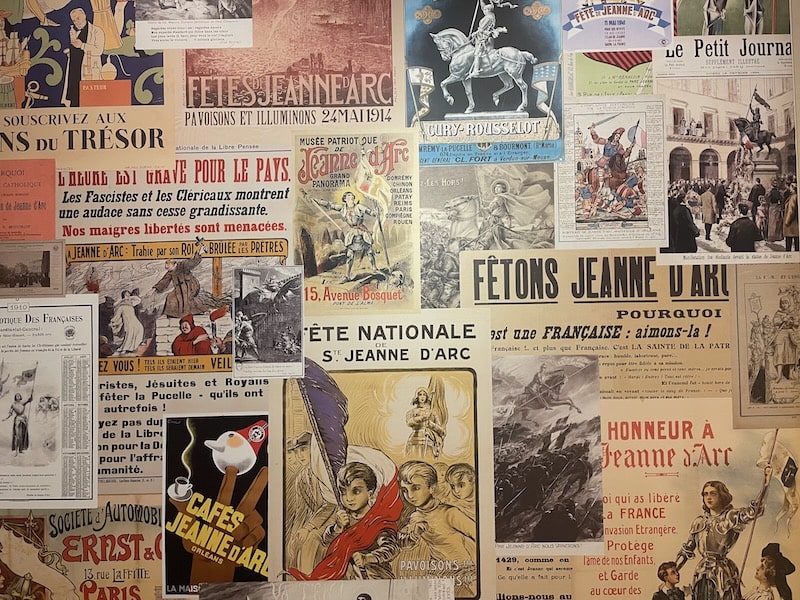

Joan of Arc as a political tool

As the 19th century rolled around, her role became more political. After all, didn’t she save France and its monarchy? Surely that can be of use…

A resounding outcome of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 was the loss to Prussia (now Germany) of the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, Joan’s birthplace. Joan was used as a symbol for the nationalism which followed, so much so that towards the end of the century, discussions began about her possible sainthood.

France had lived through anti-clerical revolutions, but the Catholic faith was in full resurgence, clearing a path towards sainthood.

A modern propaganda tool

That sainthood would take place in 1920, when she was canonized by the pope. What more formidable instrument of propaganda could you find in a Catholic country reeling from military defeat?

During World War II, she was championed by the collaborationist Vichy government, and later, by the communists. Both left- and right-wing politicians will conveniently call her theirs.

Her name and fame have been used to promote European and French unity (she unified France), the fight against racism and discrimination (her deep religiousness embraced all), repulsion of the invader (she fought the English), and the standard story of a girl of the people protecting a nation against its enemies.

But the most decried appropriation came from the far right, when Jean-Marie Le Pen of the Front National used her to promote anti-immigrant policies and a populist version of nationalism

Joan, naturally, had her detractors.

One journalist (article in French) wondered why a medieval heroine would be used to promote modern nationalism, relegating her to the level of “nice myth to teach children about patriotism”. The anti-clericals decried her elevation to religious icon status, and republicans pointed out she was a monarchist through and through.

Still, her image remains, one of strength and courage and faith, of fighting for one’s personal truths, and today as ever in history, the need for universal messages continues to exist. She belongs to no one and everyone, and her eclectic presence in Rouen is a clear example of her universal appeal.

Before you go...

If you’re keen on French history, here are other moments in French history that have made their mark:

- A Day In The Life Of Louis XIV, Sun King

- Napoleon Bonaparte: The Man The French Love To Hate

- Was The Belle Epoque In France Really THAT ‘Belle’?

- De Gaulle In Colombey Les Deux Eglises: Life & Times Of A French Hero

To relive the era of Joan of Arc, the city of Rouen celebrates her each year, on the last weekend of May, as close as possible to the 30th, day of her execution. Throughout the city, parades and medieval markets vie with troubadours and jugglers in a reenactment of mid-15th century life and commemorating the formidable, inspirational and brave soldier who led her troops from the front.

When you're in Rouen, for something completely different, make sure you don't miss two other magnificent sights – Rouen Cathedral (and its Joan of Arc Chapel), and some of Rouen's Impressionist treasures (it is, after all, known as the "capital of Impressionism").