Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Made in France ›

- The Glove-Makers of Grenoble

Is This The Last Glove-Maker Of Grenoble?

When Jean Strazzeri finished his glove-making apprenticeship in Grenoble in 1967, he was presented with a huge pair of shears.

More than half a century later, as head of the Ganterie Lesdiguières-Barnier, he still uses them to cut his kid gloves. He’s the last of his class to wield his shears because these days, making gloves by hand is a dying art.

Jean Strazzeri, glove maker extraordinaire, has used the same shears since he finished his apprenticeship in 1967 - and still uses the rest of his traditional tools

Jean Strazzeri, glove maker extraordinaire, has used the same shears since he finished his apprenticeship in 1967 - and still uses the rest of his traditional tools

We French love our fashion and there was a time when no sensible woman would be seen leaving home without her hat and gloves. I remember my mother gingerly folding back the sheet of crackling parchment paper over her pair, gently closing the lid and putting the box away on a neat little pile, in the dark recesses of her cupboard, not to be disturbed until the next occasion (or until I snuck in after she left to touch the soft leather).

It wasn't that long ago that gloves were required attire - at least for a certain social class

It wasn't that long ago that gloves were required attire - at least for a certain social classOnce upon a stylish time

These days, Grenoble is a high-tech and research hub, known for its universities and for its achingly beautiful setting in the foothills of the Alps.

The city of Grenoble: you can't ask for a more beautiful setting, can you?

The city of Grenoble: you can't ask for a more beautiful setting, can you?But 200 years ago, Grenoble was the luxury glove capital of the world, shipping to London, New York, and even further afield to Tokyo and Moscow.

The city can trace its glove-making past to 1328 and during the late 18th century, when the industry was at its height, 64 glove makers fashioned more than a million pairs each year for well-to-do customers. Glove making became the city’s lifeblood: by the 1800s, one family in two depended on it.

But the end was nearing...

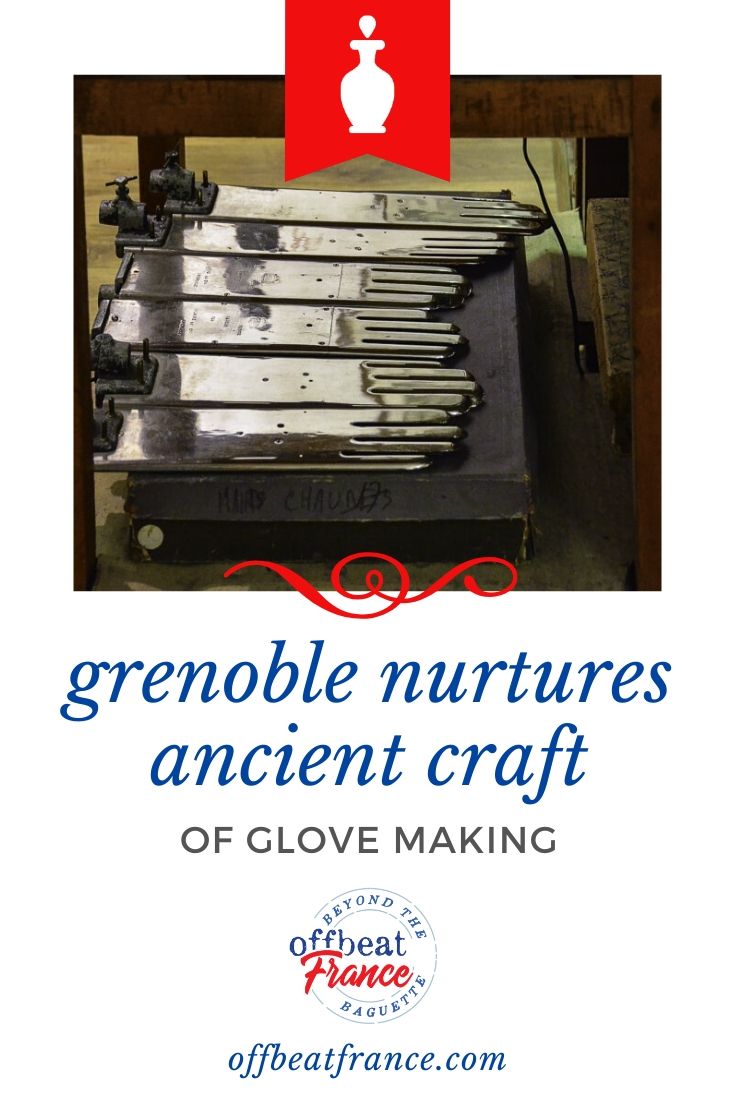

The famous 'iron hands' which allow cutting of up to ten pairs of gloves at a time - this local invention revolutionized Grenoble's glove-making industry

The famous 'iron hands' which allow cutting of up to ten pairs of gloves at a time - this local invention revolutionized Grenoble's glove-making industry The glove shop today. While quality gloves are still made inside, other products have to be sold to stay afloat, such as bags and umbrellas

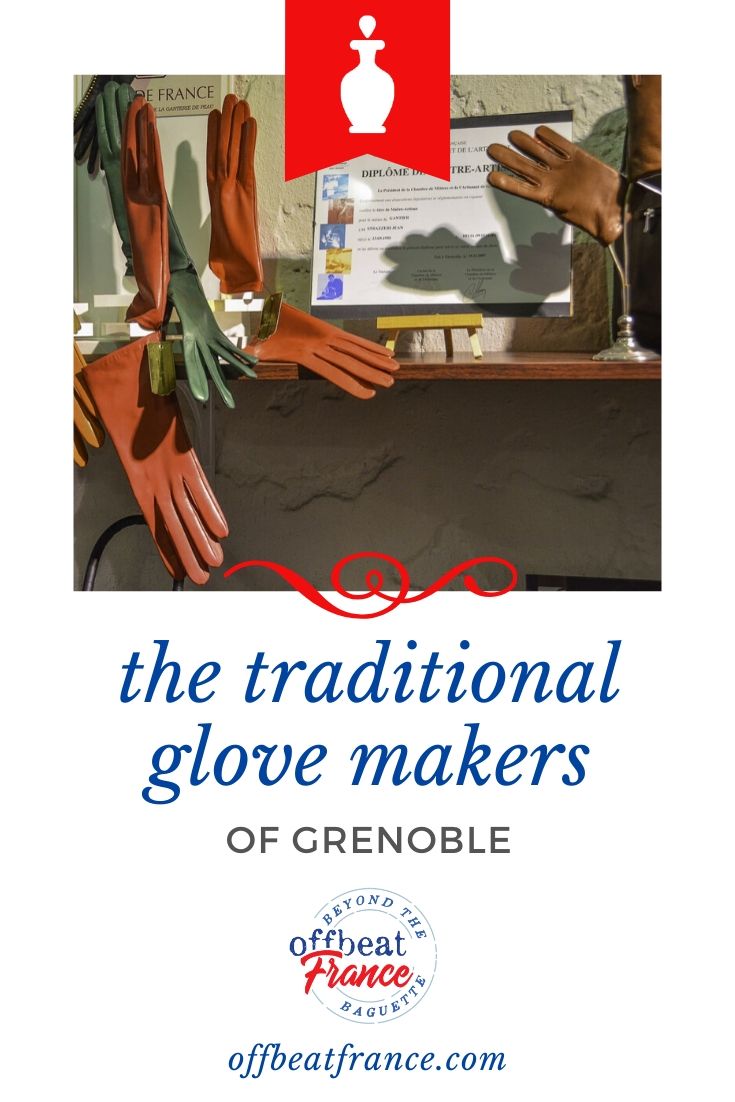

The glove shop today. While quality gloves are still made inside, other products have to be sold to stay afloat, such as bags and umbrellas“I’m the last one to continue this tradition,” Mr Strazzeri told me when I visited his shop. “There are other glove manufacturers in France but they don’t work kidskin, which is robust and keeps its strength.”

His dream is to perpetuate his craft by teaching the younger generation but apprenticeships have been cut from three years to one and that, he believes, simply isn’t long enough to train a glove maker.

“A new employee will only be able to cut six pairs of gloves in a day rather than 20, as they once did,” said Mr Strazzeri.

The glove in the display case was designed in red and black in honour of Grenoble-born writer Stendhal, who wrote "The Red and the Black", a novel of social history set in early 19th- century France. The gloves won Mr Strazzeri the coveted title of Meilleur Ouvrier de France, or Best Craftsman of France, the country’s top award for artisans. This distinction allows professionals to wear a red, white and blue ribbon around their necks or on their pocket and to use the initials MOF, a great mark of distinction.

The glove in the display case was designed in red and black in honour of Grenoble-born writer Stendhal, who wrote "The Red and the Black", a novel of social history set in early 19th- century France. The gloves won Mr Strazzeri the coveted title of Meilleur Ouvrier de France, or Best Craftsman of France, the country’s top award for artisans. This distinction allows professionals to wear a red, white and blue ribbon around their necks or on their pocket and to use the initials MOF, a great mark of distinction.Some glove backstory

Have you ever noticed how so many idioms are related to gloves? Clearly, they've left an imprint:

- hand in glove

- fit like a glove

- the gloves are off

- an iron fist in a velvet glove

- an iron hand - as in using an iron hand to shape a handmade glove!

- and appropriately in our case, handle with kid gloves.

This shouldn't surprise us because there have been gloves since there were humans. Long ago, gloves were made from leather or fur or whatever was around, and used for protection, perhaps from cold or from poisonous plants or maybe even small but angry animals.

Gloves are mentioned in Antiquity, and during the Dark Ages we know they were part of Papal vestments. Gloves continued to be part of our "equipment" during the Middle Ages, especially those made of metal, used for protection as part of an armour. When muskets and rifles replaced lances and arrows, full armours were abandoned and gloves became more of a decorative item. With time, they were refined and definitely went upmarket. Made with silks and adorned with pearls, these exquisite items were for centuries only worn by the elite.

In the Victorian era, gloves were a sign of wealth, the finer and more ornate the better. After all, wearing gloves surely meant you hadn't done a day's labour in your life (and if you happened to work with your hands, wearing gloves would camouflage that embarrassing fact and raise you in society's eyes). Gloves also helped protect you from dirt and disease.

With the arrival of the 20th century, gloves lost their shine. Feminism freed women from constricting clothes (corsets and yes, also gloves) and the wars came, during which gloves were eyed as a luxury in an era of restrictions. They made a huge comeback in the 1940s and 50s... remember those glamorous movies, heavily made-up women with gloves past their elbows? And then the 1960s struck, with their androgynous clothing and much burning of bras. Few women would be seen dead going out in hat and gloves, and gloves became practical items — for winter, or for washing dishes and gardening. Their role as an arbiter of social class was over.

But like much in history, fashion is a cycle and the embattled glove returned, showcased by none other than Madonna (as a dance prop) and Michael Jackson, he of the single glove.

A long and winding road

We don't give gloves a second thought, not even when we pull them on. I had no idea how much actually goes into making a pair of gloves, especially a quality, kidskin pair. So Mr Strazzeri obliged by explaining.

He first buys his skins from a local abattoir, leftovers from animals that have already been slaughtered for food. He then drives 570km to a tannery, where he delivers at least 600 skins each time (they won’t handle any fewer). To my surprise, all skins are returned from the tannery in — shades of white!

The kidskins are sorted into four stacks according to the colour they will be dyed: black, dark colours, pastels and those destined to become suede because their shiny side can’t be used. The stacks, along with colour samples, travel back to the tanner, this time for dyeing.

Years ago, the materials could all be purchased locally but with the demise of the industry, raw materials became scarce, hence the travel acrobatics involved in gathering all the necessary bits and pieces.

Coloured kidskin, ready to become gloves

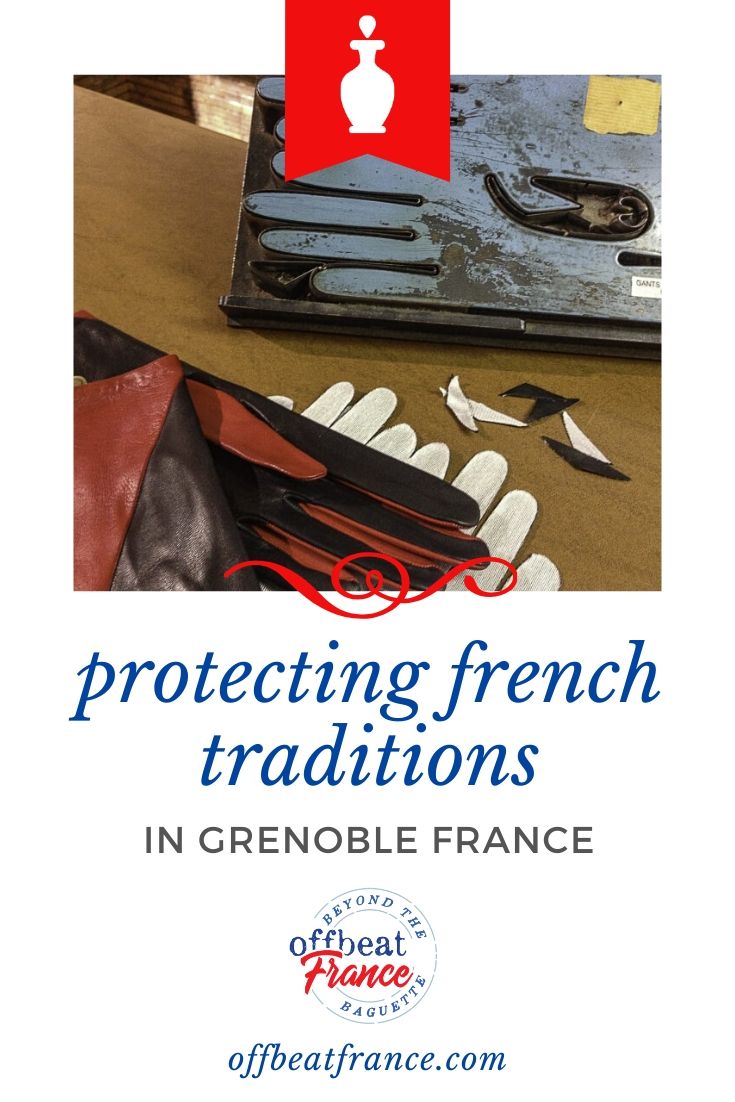

Coloured kidskin, ready to become glovesFinally, coloured skins in hand, production can begin, an artistic sequence in which skins are divided by colour and matched and sorted: two gloves, four gloves, six gloves.

The skins are moistened, stretched, and finally, cut on the ‘Iron Hand’, a local invention that can cut the fingers out of ten gloves at a time.

After cutting, each glove is lined with silk or cashmere, and the sewing begins, a veritable puzzle of 22 pieces assembled for each pair. Every piece is numbered so it isn’t lost, and sewing is done by hand or on a machine that is at least 100 years old.

The finished glove is then slipped gently onto a ‘heating hand’, the equivalent of a glove-shaped iron which smooths and straightens the tender leather.

The Ganterie, by the way, is a family affair— Mr Strazzeri admits he couldn't do it all alone.

The etiquette of wearing gloves

Like everything else in France, there's a right way and a wrong way of doing things. Gloves are no different and back when they were required attire, you had to follow rules. Like these:

- Women had to leave home with gloves on — none of this pulling your gloves on once out the door (same for your hat, by the way).

- Hot stifling summer weather? No matter. The gloves still had to be worn if you valued your reputation.

- No, you did not eat with your gloves on. You took them off discreetly, put them on your lap, laid your napkin over them and when finished eating, you could slip them back on again. (Forget what you saw in Downton Abbey!)

- Men had to wear light-coloured gloves when accompanying women so as not to dirty the pale women's gloves.

Made in France and making a comeback

Why the fuss? Isn’t a glove just a glove, after all?

Not exactly.

Kid gloves are at the summit of the glove pyramid. According to Webster's dictionary, "To handle or treat something with kid gloves is to do so with special consideration or in a tactful manner, often due to a perceived sensitivity. Kid gloves are simply gloves made from kid leather—in other words, the skin from a young goat."

Today, kid gloves are riding a gentel wave of resurgence. The Ganterie remains a small concern, producing a mere 200-300 pairs a month, but more young people are buying. Mr Strazzeri sees generations come in together, women with granddaughters, each choosing her own style. It's not quite a revival, but the luxury glove industry isn't dead yet.

Its future would have been far brighter without the inevitable flood of Far Eastern products, not handmade, not elegant, not soft and sweet like the baby kid Mr Strazzeri uses, but rough, squeaky, uneven, unattractive — and above all, cheap at €20 (US$30) a pair rather than the €60-€500 you’ll pay for a handmade pair in this shop.

There is also renewed interest in French-made products and in preserving traditional crafts in France, all of which is helps his shop survive.

Jean Strazzeri remembers glove making’s heyday and takes pride in explaining every step of his trade

Jean Strazzeri remembers glove making’s heyday and takes pride in explaining every step of his trade“There is nothing like a handmade glove,” said Mr Strazzeri. “You can always tell them apart.”

One day, in the Bon Marché department store in Paris, a shopper spotted and requested a pair of Lesdiguières-Barnier gloves from the showcase. The saleslady brought her something inferior from the back, telling her they were the same.

“No they’re not,” insisted the customer, lying them side by side. “Surely you can tell the difference. Just look at the seams. And the skin.”

Mr Strazzeri happened to be standing nearby. He beamed, and quietly walked away.

FACT BOX

- The shop welcomes groups who want a personal explanation of how authentic kid gloves are made (explanations are in French)

- You can visit the shop at 10 rue Voltaire (see map) in the Quartier des Antiquaires and while you're there, explore the area's many antique shops

- The shop is right downtown so you won't need any public transport

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!