Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Destinations ›

- Southern France ›

- Lacoste

Lacoste Village: Scandal, Style, And A Steamy History

Published 1 July 2024 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

Lacoste, France, is a tiny village in the Luberon region of Provence, but it packs a lot of history behind its beautifully restored streets and old houses. If you love villages with a story, Lacoste should be firmly on your Luberon list.

The tiny village of Lacoste in the Vaucluse department has a rambunctious history that involves everything from racy novels to golf courses to high fashion.

And plenty of cobblestoned streets.

Cobblestoned streets of Lacoste ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFrance

Cobblestoned streets of Lacoste ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFranceNOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

The medieval village of Lacoste is perched on a hill, like many villages of the Luberon region of Provence. Peering across the valley you’ll see Bonnieux, and on a clear day, far beyond, you might spot the often snowy tip of Mont Ventoux.

As you approach Lacoste, the crumbling tower of its château will be visible from a distance, its ragged silhouette a familiar sight against the sky.

The landlords

Whereas many castles in France are handed around multiple owners who may or may not leave their mark, this one has had two celebrity “chatelains”, the Marquis de Sade and Pierre Cardin.

He was known as the “Divine Marquis”

In case the name of the Marquis de Sade has somehow escaped you, he was famous, but not necessarily for the right reasons.

Born to a good family in Provence in 1740, he could have been destined to a brilliant future.

But he went wrong, early on, causing his parents plenty of grief. He married after a stint in the army, but soon was accused of blasphemy and torture by a prostitute. He was arrested and sent to jail in the Château de Vincennes, the start of a prison career that would span some 27 years during which he would learn to hate the judicial system.

Soon, his name would echo across society.

He flittered from mistress to mistress and career to career, his “criminal” side never far below the surface.

Not only did he mix with prostitutes, but he was accused of poisoning them, of practising sodomy (punishable by death in those days), of multiple sexual scandals, one involving five boys and girls.

Then came the French Revolution, in which he played an active role for a while, but even here, he was considered too subversive, questioning authority and the need for laws.

Entrance to the Château de Lacoste with its silhouette of the Marquis de Sade, by artist Daniel You ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFrance

Entrance to the Château de Lacoste with its silhouette of the Marquis de Sade, by artist Daniel You ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFranceHe narrowly escaped the guillotine and pulled out of politics to dedicate himself to writing pornographic works. Again, he was arrested for these, and would spend his final 13 years in jail.

His books would be high-profile, as much for their condemned content as for the genius of their prose, often written during one of his many prison stints. Perhaps his most famous is “The 120 Days of Sodom” which, by the way, I have not read and do not encourage you to read, as it includes violent scenes of torture and rape. You can guess where the word "sadism" came from...

As one critic, Georges Bataille, put it in the mid-20th century, “You cannot but feel ill after reading this book, even more ill than the one who wrote it.” I translate liberally, but you get the gist. Bataille called it nauseous.

For years de Sade’s works would be published clandestinely and only in the 20th century would an editor finally take the plunge and put his writing on the market openly.

For those of you interested in taking a deeper dive into de Sade's life, this article in the Smithsonian Magazine should do the trick.

Enter Pierre Cardin

More than 200 years later, another controversy would engulf the château of this tiny town when fashion designer Pierre Cardin bought it in 2001 and undertook to renovate parts of it.

Cardin’s dream was to turn the hilltop village into a cultural center, and he created a music and theater festival to draw visitors to the village, which continues to this day.

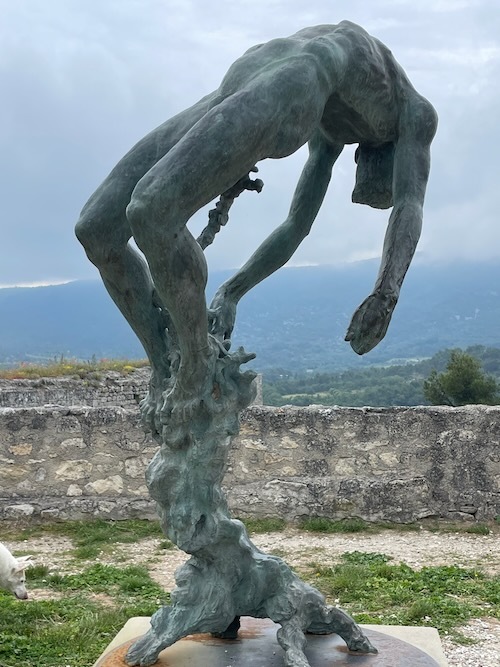

Sculptures at the castle ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFrance

Sculptures at the castle ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFrance

Initially, Cardin’s purchase was met with approval from the villagers of Lacoste. The castle was falling apart and no one else had offered to purchase and restore it. But when he started buying up buildings to house his visitors, things took a downward turn.

Rebellion brewed. Walls were tagged. Locals complained that life had been sucked out of their village.

But still people sold, for prices far above their properties’ true value, revving up tempers even more. Most of the houses remained empty throughout the year, and the few existing shops, like the boulangerie, disappeared.

While villagers protested, tourists swarmed. The village, especially those parts that had been fixed up, was drop-dead picturesque, and Cardin’s creations could be seen through well-lit shop windows.

Cardin prided himself on using local workers for his renovations, so money circulated through Lacoste, a fact even his harshest opponents had to admit. In his view, he had given the village a second life.

Eventually, the village and the designer would forge an uneasy peace, with Lacoste and its castle becoming an unavoidable stop along the Luberon tourist circuit.

The era of SCAD

For those of you who haven’t come across this acronym, it stands for Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD), which has been using the village of Lacoste as its European campus.

When Cardin died, he left behind a number of renovated buildings that soon became part of the art school, now the village’s main landlord and long-time friend of Cardin.

Medieval streets of Lacoste ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFrance

Medieval streets of Lacoste ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFranceThe school renovated buildings and streets, often leaving them better than before. During the school year, design students are fortunate – they can study in an environment where the light is beautiful, the setting pastoral, and they are surrounded by history.

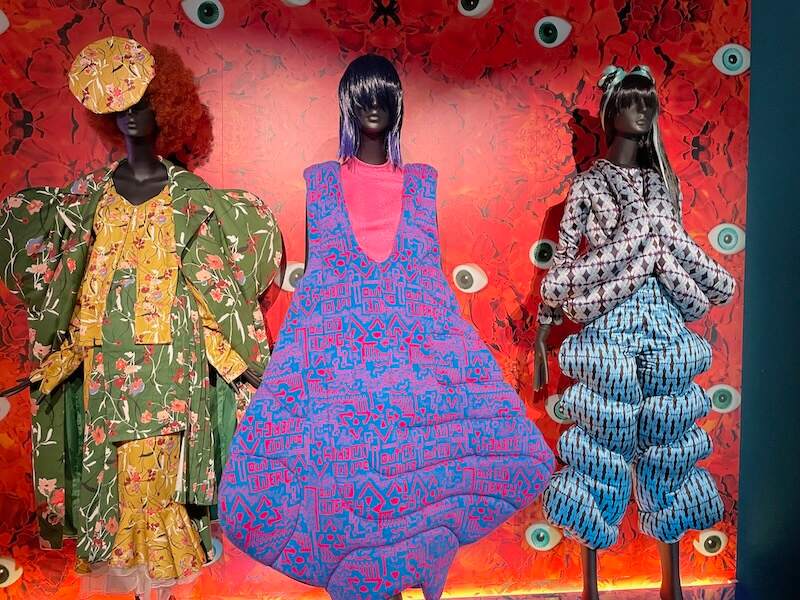

A museum of fashion and film in the village (SCAD Fash) showcases creators from both the worlds of fashion and cinema, along with major fashion innovations.

One of the several galleries in Lacoste that showcase students’ fashion creations ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFrance

One of the several galleries in Lacoste that showcase students’ fashion creations ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFranceBOOKS ABOUT THE LUBERON (to read before going!)

➽ An American in Provence by Jamie Beck

➽ A Year in Provence by Peter Mayle

➽ An Insider's Guide to Provence by Keith Van Sickle

➽ And a map!

The village

The village of Lacoste is more than just its castle, however. It is a lovely collection of cobbled streets and stone buildings. It stands proudly on the northern flanks of the Petit Luberon hill (or mountain, depending where you’re from).

I stayed in the nearby village of Bonnieux during my last visit and could see Lacoste across the valley every morning from my breakfast table: peaceful, serene, Provençal.

Even on a dim, cloudy day, the views from Lacoste are stunning. Here, you can see Bonnieux across the valley ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFrance

Even on a dim, cloudy day, the views from Lacoste are stunning. Here, you can see Bonnieux across the valley ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFranceBehind this serenity lies a history of rebellion, of violence that seems incongruous as you make your way uphill to the castle.

The early days

People have lived here for some 35,000 years.

When the Marquis de Sade was restoring his castle, workers unearthed greek amphorae and some gallo-roman ruins.

The name of Lacoste itself – at the time Costa – didn’t emerge until the Middle Ages, in the early 11th century, when the “barbarians” left town. St. Trophime church dates back to these times.

The religious wars

Lacoste had become home to settlers from the Piedmont, in what is now northern Italy. They were Vaudois, followers of Pierre Valdo, an evangelist who took a vow of poverty and launched a religious movement in 1170. He is often considered as a precursor of Protestantism, and many of his followers eventually converted to the Protestant faith.

Massacre of the Vaudois in Mérindol, a village on the south side of the Luberon mountains. Print by Gustave Doré (1832-1886) - Le Point No. 1978, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Massacre of the Vaudois in Mérindol, a village on the south side of the Luberon mountains. Print by Gustave Doré (1832-1886) - Le Point No. 1978, Public Domain, via Wikimedia CommonsThese so-called heretics would be severely persecuted. They would be raped and tortured and worse, all in the name of religion.

THE WALDENSIANS

In the early 16th century, the village of Lacoste in the Luberon region became a significant refuge for the Waldensians, a Christian movement originating in the Alps.

They were welcomed in Lacoste, much in need of manpower lost to plagues and war. But their embrace of Reformation ideas increased tensions with the Catholic Church and local authorities, particularly since Lacoste bordered the Papal States of Comtat Venaissin.

In 1545, a brutal campaign was launched against the Waldensians in the Luberon. Troops pillaged several villages, including Lacoste, confiscating lands and brutally murdering the population, forcing survivors to flee.

Over a month, the campaign destroyed 24 villages, burned 900 houses, and murdered some 3,000 Waldensians.

The violence would continue until finally, in 1598, King Henri IV (himself raised a Protestant who converted to become king) signed the Edict of Nantes, making Catholicism the religion of the realm but giving Protestants the right to practice.

But peace wouldn't last.

THE EDICT OF NANTES

France in the 16th century was a land divided by religion. Catholics, the majority, clashed with Huguenots, a Protestant group. In 1598, King Henry IV, a former Huguenot, signed the Edict of Nantes, which granted Huguenots some freedoms in a time of religious tension.

However, the peace wouldn't last and the Edict's protections weakened, with restrictions tightening. The infamous "dragonnades" of the 1680s saw soldiers harassing Huguenots to convert to Catholicism.

The final blow came in 1685. King Louis XIV, a devout Catholic, revoked the Edict of Nantes with the Edict of Fontainebleau, outlawing Protestant worship, closing churches, and limiting education. Many Huguenots, skilled artisans and thinkers, fled France for more tolerant lands, weakening France economically and tarnishing its image.

The road to regaining lost rights was long. The Edict of Toleration in 1787 offered Huguenots some relief, allowing them basic civil rights like marriage and property ownership. But true religious freedom arrived with the French Revolution in 1789, when the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen enshrined freedom of conscience for all citizens. The deal would be sealed in 1801, when Napoleon's Concordat established religious equality between Catholics and Protestants once and for all.

Visiting Lacoste

Lacoste’s contemporary history, first as Cardin’s “theater” of sorts and then as a campus town, has affected the village its life.

eroded the traditional life of the village. Gone are the shops that catered to locals, and while the streets remain stunningly picturesque, the traditional life of the Luberon is no longer coursing through its veins.

There’s still plenty to see in this impossibly gorgeous village.

At the top of the village, Cardin transformed an ancient Roman quarry into a giant outdoor theater and concert venue. Also outside the village is Saint-Trophime church (1123), an architectural jewel which has somehow retained a few pieces of its Romanesque past.

And at the bottom of the village are the Marquis' former stables, the restored Maison Basse, now used for cultural events.

In the village itself, look for the stone bell tower (dated 1793), topped by a wrought iron campanile, so striking against the Provençal sky.

The wrought iron campanile in the heart of Lacoste ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFrance

The wrought iron campanile in the heart of Lacoste ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFranceLacoste also has a former Protestant temple, remains of a previous incarnation. Today it is the communal hall, used by the village for its cultural events.

With its harried past and non-conformist present, Lacoste is a breed apart, a village whose traditions may have disappeared but which, in some unexpected ways, has been reborn.

Keep that in mind as you slowly make your way uphill to the castle, and remember to wear shoes that grip, especially if there's rain.

It’s as though this cat knew it was headed for fame and fortune by striking a pose! ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFrance

It’s as though this cat knew it was headed for fame and fortune by striking a pose! ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFranceTake a break from exploring at one of the village's two cafés, but know that there are few places to stay in Lacoste proper.

Since you can’t really reach it by public transport (there's a bus from a nearby village but...), I’ll assume you have a car, in which case I suggest you do what I did and stay in Bonnieux, a ten-minute drive. I can recommend these two accommodations in Bonnieux:

- Clos du Buis hotel

- Bonheur en Bonnieux apartment, perfect if you're staying for a week or more and if there are several of you – it sleeps five