Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Culture & Civilization ›

- Renaissance to Republic ›

- General de Gaulle

De Gaulle in Colombey les Deux Eglises: Life & Times of a French Hero

Published 15 October 2022 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

I grew up hearing about de Gaulle, as did many of my generation. He was President of France throughout my childhood and I'd always wanted to know more about him. My recent trip to his former home in northeastern France filled in those blanks.

General Charles de Gaulle has one of the best-known names in France: it ranks up there with Louis XIV and Napoleon.

In contrast to their grandiosity and opulence, De Gaulle lived in comparative modesty. His was a compact country house on the edge of a tiny village of the Haute Marne département, called Colombey-les-Deux-Eglises.

La Boisserie, his home, was so modest it had no running water when De Gaulle first bought it in 1934. He would live here intermittently throughout his life, more like a private citizen than the head of state he would become, taking part in village life, writing his memoirs, and spending his time exploring the nearby hills and forests.

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

A short biography of De Gaulle

Rest assured, I’m not about to drag you through decades of 20th-century history or politics, but I do have to refresh your memory about De Gaulle’s life, without which a visit to Colombey would make very little sense.

Born in northern France, De Gaulle grew up feeling his destiny would be historic, and everything he did was designed to make that destiny come true. At school, if there was a play with a regal role, he would always be the King of France.

First educated by the Jesuits, he would become a career military man and fight in World War I. Unable to stomach the Vichy regime's appeasement of Nazi Germany in World War II, he fled to Britain. From London, he led the Free French forces and became their voice on BBC Radio. He will forever be remembered for his radio call for resistance on 18 June 1940, an address deemed so unimportant at the time the BBC didn't bother to record it.

Charles de Gaulle broadcasting on the BBC out of London

Charles de Gaulle broadcasting on the BBC out of London August 1944, a triumphant De Gaulle enters a liberated Paris

August 1944, a triumphant De Gaulle enters a liberated ParisWhen the Allies finally marched into France after the D-Day victory, he was the country’s undisputed leader. Over the years, he would be in and out of politics, serving as President of France for a decade, often a controversial figure, seen as arrogant and stubborn, but rarely leaving anyone indifferent.

WANT TO KNOW MORE ABOUT DE GAULLE?

A Certain Idea of France, by Julian Jackson, is a thorough biography of De Gaulle. It looks at events in which he played a pivotal role – the Algerian War, the creation of the Fifth Republic, and the revival of France as a global power. An absolute must-read if this period in history speaks to you. Buy from Amazon

La Boisserie, home of Charles de Gaulle

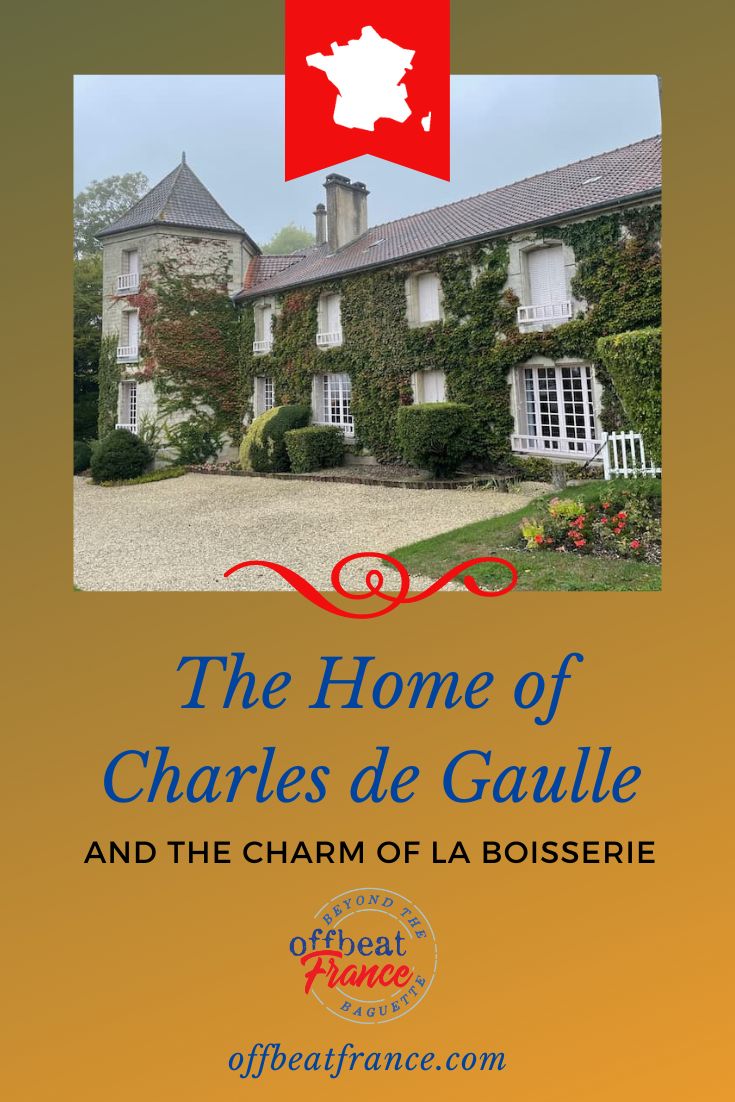

In late summer, La Boisserie looks like a typical gentilhommière, the name given to manor houses belonging to gentlemen of noble birth, with vines creeping towards the windows and embraced by a well-manicured garden.

The 14-room house was initially built in the early 19th century and was used for years as the local pub, which in French is called a brasserie, probably accounting for its present name, La Boisserie.

De Gaulle was still a colonel with a modest salary when he bought the house in 1934, so he and his wife Yvonne used a typically French system called viager, whereby the buyer pays rent throughout the seller's lifetime.

It's a roll of the dice.

If the owner lives to ripe old age, the buyer may pay well over the market price for a home. In De Gaulle's case, the owner died after just two years, handing him the financial bonanza of a lifetime.

La Boisserie as it is today - De Gaulle's office is located in the small tower ©OffbeatFrance

La Boisserie as it is today - De Gaulle's office is located in the small tower ©OffbeatFranceThe house was perfect.

First, it was located between Paris and what was France’s Eastern front during wars with Germany. With De Gaulle in the military, he could expected to be stationed somewhere along this axis.

Second, it would give the family a home base, an important anchor given the perpertual movement of a military man.

Finally, and possibly most important, it would provide a refuge for his daughter Anne, who had Down’s syndrome and needed a place of peace in the countryside. His two other children would long remember the pleasant weekends and summers spent here, interrupted only by the start of World War II.

At war’s end, the De Gaulles found their house pillaged and burned, although not to the ground. They began renovations, and built the little tower that would house his office (and, finally, install central heating).

The war over, they would live here full-time.

'Whatever happens, the flame of the French Resistance must not be extinguished, and will not be extinguished." (Quoi qu'il arrive, la Flamme de la résistance française ne doit pas s'éteindre et ne s'éteindra pas.)

— General Charles de Gaulle, from London, 18 June 1940

The lack of conveniences at home was almost unheard of for a man of his stature.

For example, he rarely used the telephone, which he despised, and when he finally gave in and had it installed, he hid it in a cupboard under the stairs. An aide-de-camp would answer if it rang or would handle outgoing calls, with De Gaulle appearing only at the last minute.

La Boisserie was De Gaulle’s refuge, the one place he could let his guard down and show the emotions he hid in his professional life (some less kind souls would claim he had no emotions to hide).

This is where he wrote his books, elaborated his theories, and renewed his energies. This is the home of a writer and thinker, not of a soldier – there is a distinct absence of anything military.

Looking around the house, you may begin to believe you have an insight into this giant man's personality (he was 1m 96, or 6'4" tall, often nicknamed The Great Asparagus). Be forewarned: no photos are allowed inside, so the few below have come from the official sources.

The house is a snapshot in time: once Yvonne left the house in 1978 (she died a year later), nothing was ever touched again, or hardly.

The entrance

You can't miss the set of giant elephant tusks against a wall. The general disliked hunting intensely, but these tusks were a gift from Cameroon, who joined his resistance effort early, in 1940. He displayed them as a memento to the sacrifice and engagements of France's colonial troops.

And under the stairway (which leads to the family's private quarters) is the famous door which protected the telephone cupboard.

The dining room

The main item in this room is a wonderful Aubusson tapestry on the wall, along with a collection of eclectic personal gifts, like a large stainless steel rooster from the Lille international fair – he never lost that personal connection with his origins. His childhood house in Lille is now a museum (website in French), celebrated as the birthplace of Charles de Gaulle.

The dining room also displays the original street name plaque of the Rue Princesse, the street where De Gaulle was born.

A large chimney with blue tiles from Delft dominates the room and came with the house when they bought it.

As an aside, the many gifts displayed here and in the other rooms were personal gifts made to De Gaulle, not official gifts made to France. The austerity he demonstrated in his private life extended to a rigor involving state property. Given the many scandals France would later undergo concerning money – remember Giscard's diamonds? – this differentiated him even further from the traditional political class.

The formal living room

This formal room was not where the general and his wife spent their evenings: it is exactly the type of room that looks perfect from a distance but in which you would avoid sitting for fear of breaking a chair.

The formal living room - you can see the glass cabinet with the Pietà in the far corner. Photo ©Ph.Lemoine.Coll.MDT52

The formal living room - you can see the glass cabinet with the Pietà in the far corner. Photo ©Ph.Lemoine.Coll.MDT52Let your eyes be drawn to the far corner glass display – it is full of interesting objects, the most treasured of which was a 15th-century Pietá statue of Mary holding Jesus, the perfect gift for a deeply Catholic woman. It was hand-carried to Colombey by Germany's first chancellor after the war, Konrad Adenauer, the only international leader ever to be invited to the general’s home.

Adenauer's gift to Yvonne de Gaulle was not an official one, but a cadeau for the wife of a friend who was his hostess.

Adenauer's visit was highly controversial on both sides of the border. The war had barely ended (he came in 1958) and many thought any visit by a German, however anti-Hitler, was out of place.

For De Gaulle, the future of France and of Europe inevitably involved reconciliation with Germany, and he hoped that by inviting the German chancellor to his home, he would be leading by example. It held all the more meaning since several of De Gaulle's family members had been deported and imprisoned in concentration camps.

When La Boisserie was restored after the wartime fire, a library was added and would become the room where the couple gathered, leaving the living room for more formal occasions.

The library

Walking down the hall, the next room you encounter is the library: this is the room in which he died, playing solitaire at his card table.

This, to me, was the second most interesting room in the house (the first was his office, which I describe below).

The library is filled to the brim with memories and souvenirs, gifts and books, many of the contents pointing to De Gaulle the man at least as much as to De Gaulle the leader.

One of the curiosities is a cigar box containing cigars with De Gaulle's name, a 1968 gift from Fidel Castro; the two men had never met.

Lining the top of the bookcases are a series of photographs in black and white of many of the world leaders De Gaulle had either known or liked... including the royal ruling couples of Denmark, Jordan, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, the Shah of Iran and his wife, the Bey of Tunis, Churchill, Eisenhower...

La Boisserie library - not the row of photographs above the bookshelves. Photo Gzen92, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

La Boisserie library - not the row of photographs above the bookshelves. Photo Gzen92, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia CommonsA small collection of mining lamps held a special meaning, since they were given to him by miners in his beloved North. He was much respected there not only for his origins, but because he was the only political leader ever to have actually descended into the mines.

The De Gaulles belonged to the last generation before mass consumption – they had lived through the privations of war and had an innate drive to conserve energy.

In the library, Yvonne sat behind her husband, while he had his back to her. Between then was a tall lamp with a single bulb, designed to light them both.

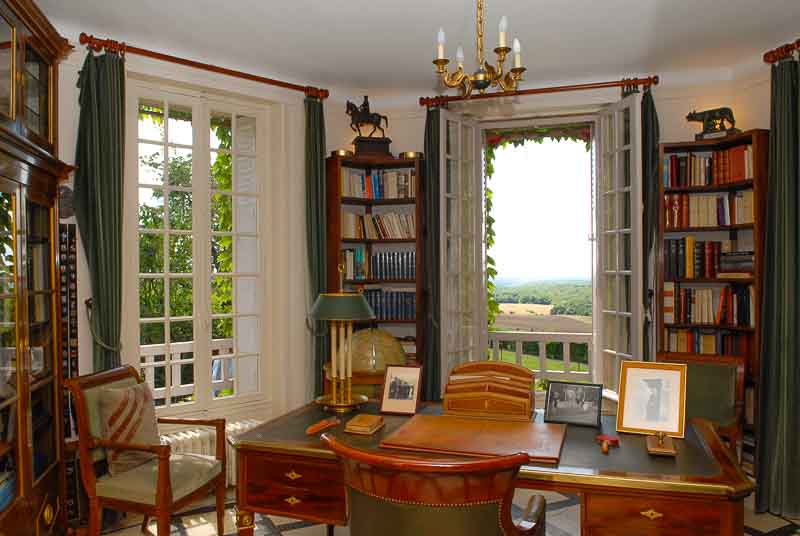

The General’s office

This is La Boisserie's pièce de résistance.

It wasn't part of the original house and was built into the new tower addition.

Elegant and simple, its bay windows open up onto the rolling hills of the region and the Clairvaux forest. As De Gaulle sat at his desk, his back to the door, who knows what was rushing through his constantly active mind.

It was the general's private haven.

Today, a glass door separates it from the library, allowing visitors to see in but not to enter. In De Gaulle's time, the glass door was made of solid oak. His children, and later his grandchildren, all knew better than to enter or even knock at the door. That privilege was reserved for Yvonne.

De Gaulles office at La Boisserie ©Ph.Lemoine.Coll.MDT52

De Gaulles office at La Boisserie ©Ph.Lemoine.Coll.MDT52The park

While the garden adjacent to the house is well tended, the more than 2ha of park around it are less so.

There is a miniature golf course, now a little overgrown, and a tennis court, but no signs of a swimming pool – a plastic pool, donated by US President Kennedy, was dragged out during the summer.

The park looks less precise than the garden because the De Gaulles believed in recycling and conservation. Rather than mow all the grass, they allowed local farmers to cut it and cart it away, so the cutting has been done either by hand or with farm machinery, not with a precise lawnmower.

The park served another purpose: when De Gaulle received important guests, he would take them for a walk rather than sit in the living room to talk. That must have been a challenge for anyone shorter than he was!

Today, La Boisserie remains a family home. As of this writing (November 2022), it belonged to Admiral Philippe de Gaulle, the general's son, aged 101. Family members still visit and use the bedrooms and kitchen, which is why access to the upper floor is not allowed.

More than half a century after De Gaulle's death, a steady stream of visitors continues to make La Boisserie part of their French itineraries.

Beyond La Boisserie, they also visit the village of Colombey-les-Deux-Eglises, the Lorraine Cross, and the De Gaulle Memorial.

Colombey les Deux Eglises, his village

If Colombey-les-Deux-Eglises is on the map today, it is because Charles de Gaulle elected to live here.

It is a peaceful, typical French village, with ancient streets and wooden shutters, centered around a tiny main square, itself bordered by the village church and cemetery.

The center of Colombey-les-Deux-Eglises. Photo Marc Ryckaert, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The center of Colombey-les-Deux-Eglises. Photo Marc Ryckaert, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia CommonsBy the way, although "deux églises" means "two churches", don't bother looking for the second one – it no longer exists.

The church is much like any other village church, with ageing, uncomfortable wooden pews, one of which belonged to the De Gaulle family. Staunch Catholics, they would attend Mass on Sundays here whenever they were in residence, sitting on a pew they inherited when they bought their house.

Given De Gaulle's height, the row containing his pew had to be widened so that his long legs could fit into it.

The church pew belonging to the De Gaulle family in the local church at Colombey ©OffbeatFrance

The church pew belonging to the De Gaulle family in the local church at Colombey ©OffbeatFranceThe grave of General de Gaulle is not what you’d expect for a head of state, but very much what you’d expect from the general himself: simple, sober, modest. He lies next to his wife, right across from his daughter Anne de Gaulle, who died at 20.

In his will, he made it clear he didn't want a state funeral, or rifles, or any of the ceremonies that would normally befit someone of his rank.

The graves of Yvonne and Charles de Gaulle ©OffbeatFrance

The graves of Yvonne and Charles de Gaulle ©OffbeatFranceIf you're facing his headstone, you can see a small guardhouse on the left where a policeman often stands guard over De Gaulle's grave.

It takes only a few seconds to notice you’re not in an everyday church graveyard: throughout the cemetery, hundreds of plaques from regiments, associations and institutions line the walls, crowding the alleys to overflowing.

The General may not have wanted pomp and circumstance, but he couldn't prevent his many admirers from posthumously paying their respects.

The Colombey church and graveyard, with the many plaques honoring Charles de Gaulle ©OffbeatFrance

The Colombey church and graveyard, with the many plaques honoring Charles de Gaulle ©OffbeatFranceThe Lorraine Cross

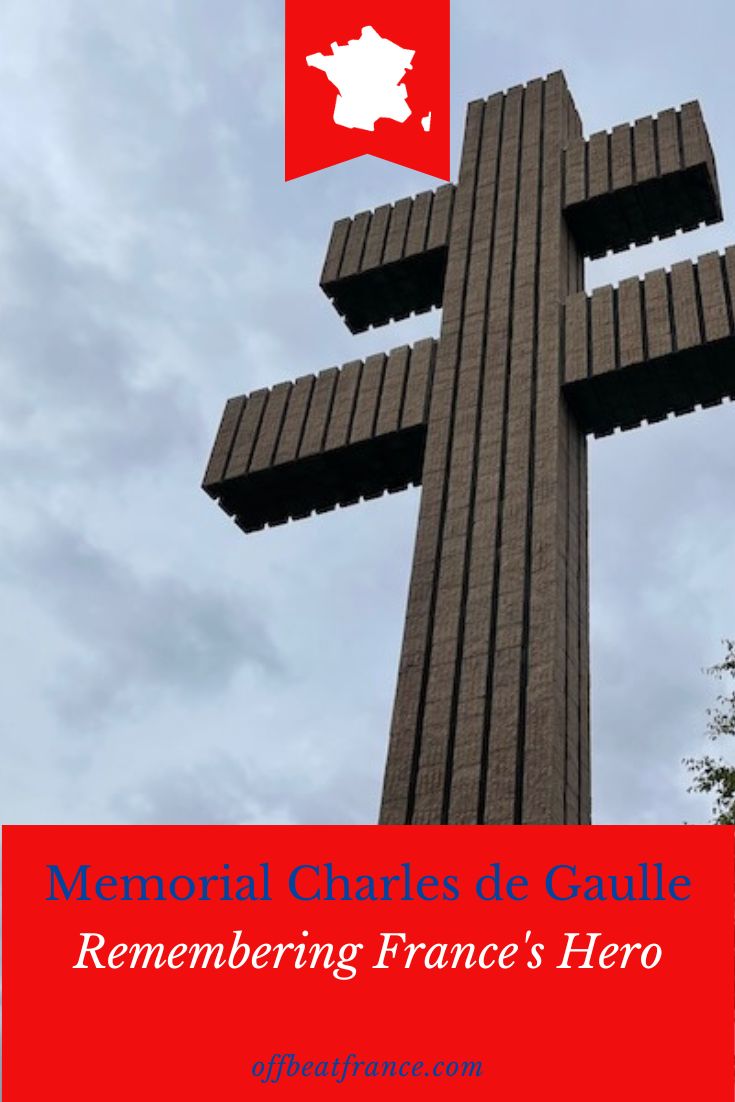

A few minutes from Colombey, the Croix de Lorraine towers over the horizon, a massive monument that dwarfs even the tallest who stand next to it.

The cross, by the way, is an ancient symbol brought back from the Crusades. The Free French Forces adopted it as their own.

General de Gaulle had voiced the idea of building a monumental cross back in 1954, although he also predicted no one would visit. He was wrong on the second count: nearly half a million people visited the cross the year it opened, in 1972.

Many contributed funds to help build the cross, including diehard Gaullists but also millions of individual French donors around the world. They raised a whopping 5.5 million francs (the currency before the euro), which not only paid for the cross but for 35 hectares of adjoining land.

A FEW FACTS ABOUT THE LORRAINE CROSS

- Height: 44.3m (145ft)

- Weight: 950 tons

- Material: pink granite from Brittany and reinforced concrete, covered in bronze plaques

- Workers: 350 took part in the construction

- Inaugurated: 18 June 1972, 32 years to a day after De Gaulle's first epic radio broadcast

The Memorial Charles de Gaulle Museum

Behind the cross, a massive memorial museum retraces De Gaulle’s life, along with the many places, events and objects that marked it.

Remember, he was born in 1890 during the Belle Epoque, was active through two world wars, the liberation of France, and the birth of the Fifth Republic in 1958, when a new constitution came into effect. That's a lot of ground to cover.

People would have listened to De Gaulle's June 1940 speech on a radio not too unlike this one ©OffbeatFrance

People would have listened to De Gaulle's June 1940 speech on a radio not too unlike this one ©OffbeatFranceThe Memorial De Gaulle is immersive and through the sense tries to place you at the sites De Gaulle would have experienced – you can walk through a World War I trench, sense the Sahara Desert, scramble over cobblestones in Paris during the 1968 student revolts... or stand next to his official black Citroën.

General de Gaulle's official Citroen ©OffbeatFrance

General de Gaulle's official Citroen ©OffbeatFranceI spent two hours in the museum and it was not enough time for this amazing venue, filled with history and memorabilia. You'll find plenty of English-language explanations so you won't have to struggle to understand what you're looking at.

Restaurants in Colombey les Deux Eglises

Once you're in Colombey, I suggest you spend a night, or at least a full day. To eat, here are my personal recommendations, tried and tested, for surprisingly good cuisine in such a tiny place.

L'Inter'Val

This little restaurant surprised me. It sits on the main square in Colombey and from the outside looks like a regional shop – which in fact it is, filled with local products and wines (and two local champagne brands).

They have several set menus (you'll find them on their Facebook page) but at the door, there's a daily blackboard with specials. For these, you'll have to show up early!

I had a memorable dessert – a deconstructed Tarte Tatin, which is a hot apple pie. All the elements were there, but ordered differently.

The deconstructed Tarte Tatin at l'Interv'al in Colombey ©OffbeatFrance

The deconstructed Tarte Tatin at l'Interv'al in Colombey ©OffbeatFranceChez Natali

If part of your joy during travel is to try fabulous restaurants (with Michelin stars if possible!) then this is where you should head. Not only is the food superb, but Chez Natali had the reputation in 2021 of being the cheapest Michelin-starred restaurant in the world.

That doesn't mean it's rock bottom, and it had to raise its prices so it may not be the cheapest, but you will pay a lot less than in some sister establishments, and get plenty for your money.

The chef, Jean-Baptiste Natali, received his Michelin star at the age of 27 (that was in 2002), the youngest chef to win the coveted award. Not only that, but he's kept it over the years (and we know how fickle those star-makers can be).

As for the food, it's what you would expect in a starred establishment. I can't remember every ingredient, but I ordered the creamiest of pumpkin soups, a veal filet mignon, and a sensory stand-out – another deconstruction, this time of a pear dessert, designed as a trompe l'oeil to fool the eye: the pear-shaped structure was a thin meringue, with the pear flavor coming from other elements on the plate. Sublime!

Hotels in Colombey les Deux Eglises

I have two stellar recommendations for hotels in Colombey-les-Deux-Eglises.

Once you've had dinner at Chez Natali, walk downstairs to spend the night in the upmarket Hostellerie La Montagne, Colombey. It is a traditional building with plenty of stone and wood, but with touches of whimsy and an offbeat flair. It only has nine rooms, but each is different and stylish, as you'd expect from a hotel twinned with a Michelin-starred restaurant.

More modest but equally worth your stay is La Grange du Relais. This old postal inn at the entrance to town, with its cheerful blue shutters and tiled roof, is still only a few minutes' walk to La Boisserie. My room on the main floor had a little garden outside, so I could sit at my little table and have a snack or work away (the wifi did reach the garden!)

How to get to Colombey les Deux Eglises

You CAN get here by public transport, but the journey, four hours at least, is too long to make this a day trip. If you don't have a car and are coming from Paris, take the regional train from the Paris Gare de l'Est to Chaumont, and then take bus #4 to Colombey (you can reserve your bus here).

Driving to Colombey is by far the best option, if you can – under three hours along the A5 from Paris towards Troyes, or under an hour from Langres, a town which should be part of your visit if you're in the Haute-Marne département.

If you need to rent a car, check prices and availability at Discovercars, the agency I use.

When I first decided to visit Colombey, I expected a few dry exhibits extolling the life of General de Gaulle. What I didn't expect was to be swept along in a history that – while I only witnessed its very end – tells us plenty about today's France and reminds us that history is about all of us.

Essential France travel resources

BOOK YOUR ACCOMMODATIONS

I use booking.com: for their huge inventory and for their easy cancellation policies

FLIGHT DELAYED OR CANCELED?

AirHelp can get you compensation (it works, I've used it)

DO YOU NEED A SIM CARD FOR FRANCE?

Here's the one I use when I travel abroad

PROTECT YOUR BELONGINGS

Keep pickpockets away with an anti-theft purse or an infinity scarf - and your identity with a VPN (I'm using Nord VPN)

TRAVEL INSURANCE

I recommend Visitors' Coverage or SafetyWing. for health away from home

GETTING FROM A TO B

I use Discovercars to rent cars and either Omio or RailEurope for train tickets

TO READ ABOUT FRANCE

Here's my long list of books about France

AND DON'T FORGET YOUR GUIDEBOOKS!

➽ Lonely Planet's Best Road Trips France

➽ DK Witness Road Trips France

➽ Any of the Green Guides series

➽ And, while you're at it, why not a map of France?

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!

BOOKS to help you travel