Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Destinations ›

- Southern France ›

- The Plague Wall

Mur de la peste: when the epidemic struck, they built a wall

When Eugène headed for the next village over to buy some olive oil, he was asked for his permit, his attestation, proof that he was coming from an uncontaminated village.

He didn't have it with him, so he was turned away by the armed guards tasked with checking.

The government had banned all travel between regions in an effort to keep the epidemic from spreading. Markets were closed, and you needed a pressing reason to leave your house.

Large get-togethers were forbidden, and those with the means abandoned the city to hide away in their country homes. The less wealthy also sought escape, to the fields or mountains or into caves.

Eventually, the vise would grow tighter. Leaving the city would be forbidden, and guards would prevent people from leaving their home if someone had died of infection there.

The year is 1721, the month is May, and the epidemic is the Great Plague, not COVID-19. Eugène may be the fruit of my imagination, but hundreds like him undoubtedly existed, everyday citizens stopped from going about their business by an invisible force they couldn't begin to understand.

The busy port of 18th-century Marseille. With permission from the Médiathèque Simone Veil de Valenciennes

The busy port of 18th-century Marseille. With permission from the Médiathèque Simone Veil de ValenciennesHow the plague came to France... and kept coming

Plague is nothing new in France. It first appeared in Gaul in the sixth century CE, and then resurfaced every century or so, disappearing until the next wave. Some episodes killed a few hundred people, others killed millions. The 1346 plague, for example, was responsible for 25 million deaths across Europe.

Plagues during the 16th and 17th centuries affected Provence disproportionately, but the Big One was the plague of 1720, known as the Great Plague.

Caused by the Yersinia pestis bacterium, it arrived in Marseille on board a ship from the Levant, the Grand Saint Antoine, on which several sailors were already known to be infected. Quarantine was common for infested ships and this was no exception.

But Marseille's warehouses were overflowing with valuable imports, ready for sale or shipment to the New World. Businessmen had no intention of letting their goods gather dust just because a few sailors were ill... proving the adage "history repeats itself".

They were also in a hurry to get their goods to a nearby fair, a major commercial event bound to make them richer. To make things worse, one of Marseille's leading magistrates owned part of the ship and its lucrative contents, weighing in heavily on the decision to prematurely lift the quarantine.

Far too soon, workers began unloading the silk and cotton cargo. In a pattern far too familiar, greed would cost many lives.

Within days, Marseille was was on its knees. Officials used propaganda to spread misinformation, claiming it was a type of flu... By the time the bubonic plague was finally acknowledged, the medical system had broken down, and mass graves overflowed, unable to hold the dead. This scene painted by Michel Serre depicts Marseille in the throes of the plague.

It took two months for proper action to be taken but by then, corpses lay scattered throughout the city, abandoned right where they had died.

Between August and October of 1720, too many bodies covered the ground to be picked up. During the two years it lasted, Western Europe's last major outbreak of bubonic plague would end up costing Provence 126,000 lives.

Building a wall to keep out the plague

At the time of the Great Plague, the Vaucluse département we know today did not exist. In its place was the Comtat Venaissin, a papal enclave which would only become part of France in 1791, during the French Revolution.

The Comtat and the neighbouring city of Avignon, also papal land, watched anxiously as the plague moved inexorably towards them from Marseille.

By September 1720, the plague had reached Apt and the difficult decision was made to cut off all traffic between Provence, the kingdom of France, the Comtat Venaissin and the Dauphiné, further north. This would be tantamount to economic suicide, given the strength of the textile manufacturing sector in the Comtat, but it had to be done.

To try to keep out the plague, a wall would stretch 27km across the Luberon, along the border between the Comtat Venaissin and the County of Provence, preventing the epidemic from spreading to Avignon and beyond. It would be two meters high (more than six feet) and half a meter thick.

Some 500 men worked for five months, gathering stones and piling them on top of one another.

Building was slow; pay was low and with harvest season coming up, workers were hard to find. Eventually, the wall was handed over to local authorities: each community would be responsible for building its own section. It was duly completed by July 1721 and was guarded by 1000 soldiers, with orders to shoot anyone who ventured across (slightly more dissuasive than the fines for moving around during Covid-19).

Eventually the plague would reach Avignon and in a twist of fate, the wall built to protect Avignon from Provence would henceforth be used to protect Provence from the plague now spreading through Avignon.

This would all end by 1723, when the epidemic died out and the wall was abandoned.

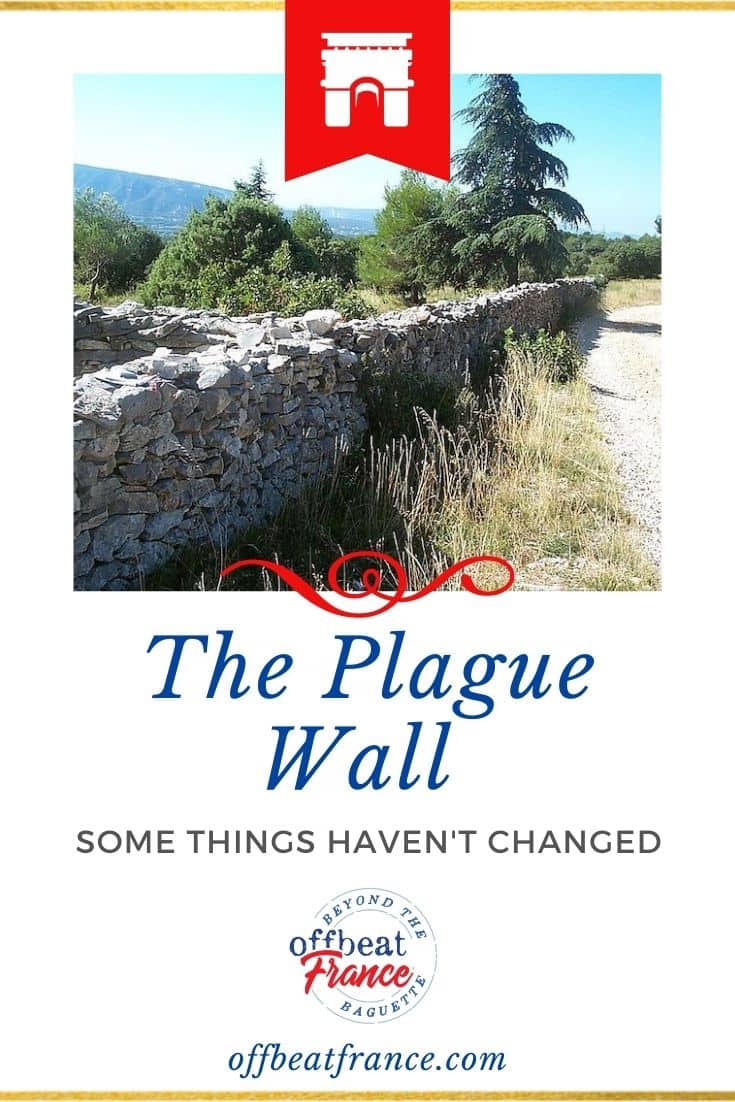

Part of the Plague Wall and the remnants of a guard station (Photo Psycho Chicken, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Part of the Plague Wall and the remnants of a guard station (Photo Psycho Chicken, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)Et ce serpent ruiné sans rien qui tienne ensemble ses écailles

Le long cheminement qui est ce qui reste d’une muraille…

On a depuis belle lurette oublié ce qu’il délimite

Et que ce fut le grand terrain domanial de l’épidémie…

And this ruined serpent, with nothing to hold together its scales, the long path, all that is left of a wall, we have long forgotten what it divides, and that it was the land of the epidemic...

The stone wall would start to crumble and locals would use the stones to build their houses. Vegetation would creep over the wall and it would almost disappear.

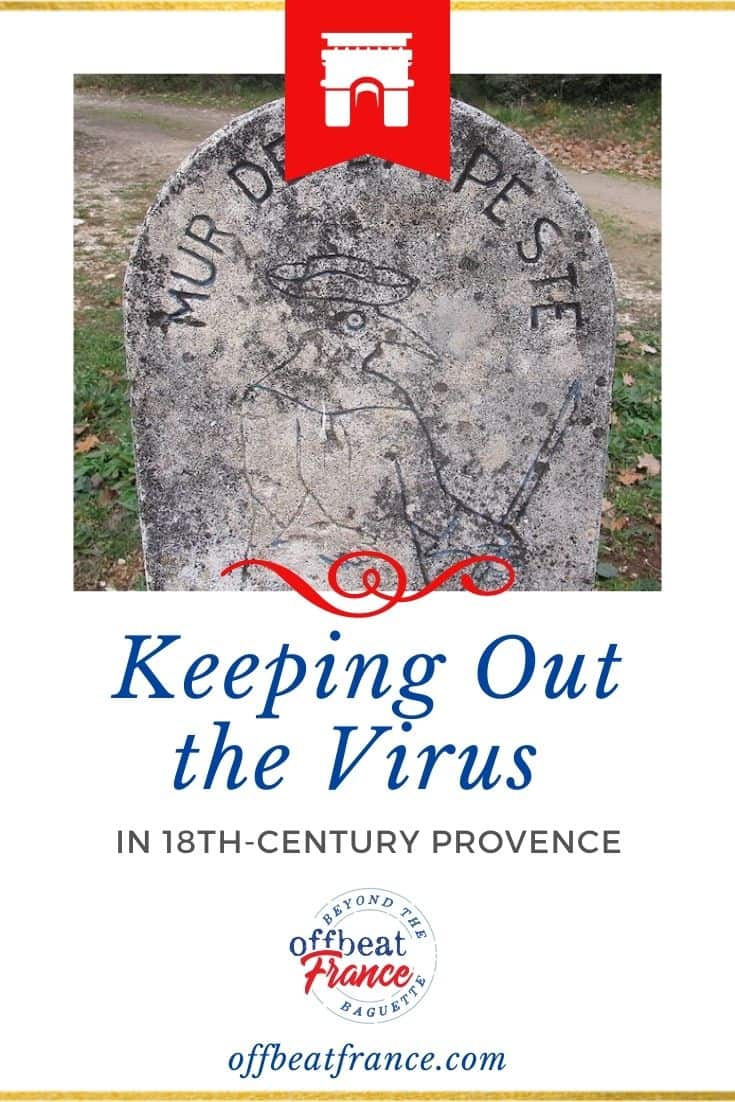

It reemerged in literature and in the 1980s, an association called "Pierre Sèche en Vaucluse" (the site is in French) decided to get involved.

The association's name, by the way, stands for "dry stone in the Vaucluse", the département in which you'll find the wall. The group began to survey the entire length of the Mur de la Peste and to help restore part of the wall so it could be visited and to preserve its historical value.

You might also like these stories!

What's left of the wall, and where to find it

Finding what's left of the wall is easier said than done: everyone talks about it, tourist offices mention it in their brochures, but when it comes to pinpointing its location, things get a bit more complicated.

It turns out there are several pieces of wall, and each piece has several access points.

I managed to find one...

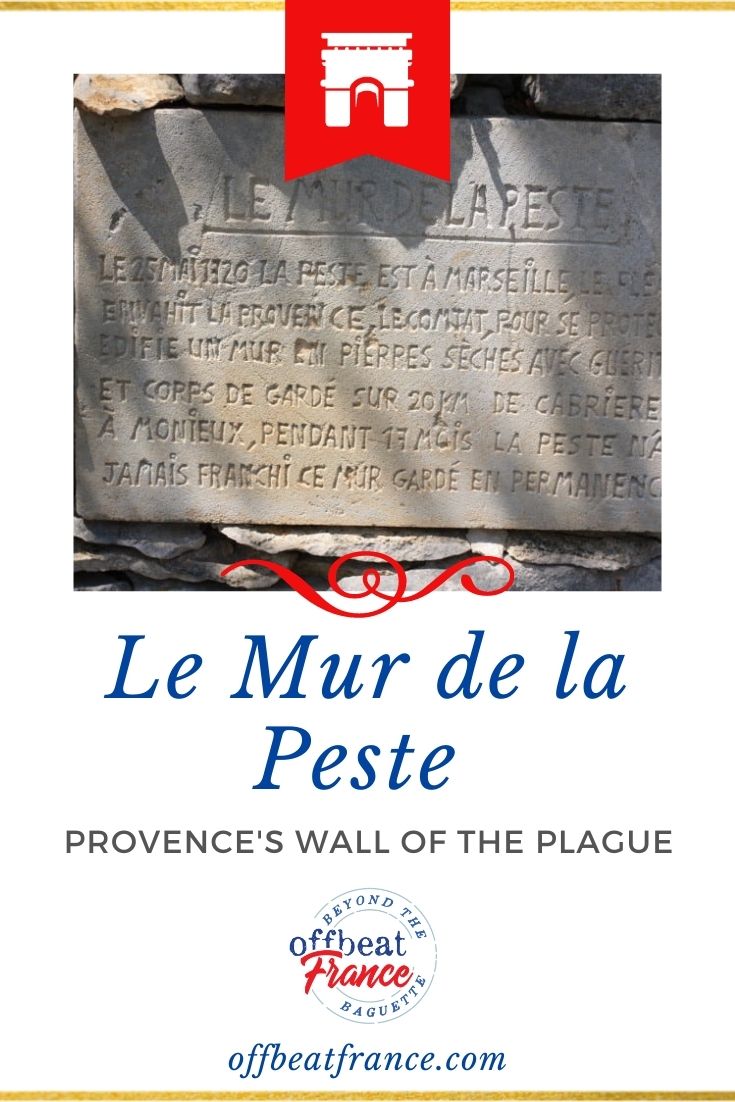

Commemorative plaque of the Mur de la Peste. Photo HOCQUEL A - VPA, courtesy Vaucluse Provence Tourisme.

Commemorative plaque of the Mur de la Peste. Photo HOCQUEL A - VPA, courtesy Vaucluse Provence Tourisme.Hiking the Mur de la Peste

Clearly, my own sense of direction leaves something to be desired, since everyone else seems to find the wall easily, whereas I struggled! I suspect I should have started at Cabrières d'Avignon rather than Lagnes, as did this hiker.

No matter. I still found it.

Leave the village of Lagnes and head for Cabrières d'Avignon along the D100 (this is in that part of Provence which is home to ali those lovely hilltop villages of the Luberon). Look for a small clearing with parked cars, called the Stèle du Maquis du Chat. It is a small monument in honour of Jean Garcin, a resistance fighter who ran a chapter of the French maquis during World War II – they used to meet at this spot, at the top of a hill. From here, just follow the signs for the Mur de la Peste, either on foot or on your mountain bike.

It's a ten-minute walk through a woodland, an easy rolling stroll. Eventually you'll see the wall, unmissable with its stones wedged against one another. I followed it for 20 minutes but I could see it went on far beyond. While the stones were crumbling and the wall was in disrepair, it is still very much identifiable as the Mur de la Peste.

Not quite the restored bit of the Plague Wall...

Not quite the restored bit of the Plague Wall...Additional sections of the Plague Wall

Another access further down the road, still heading towards Cabrières d'Avignon, is also on your left, marked with a tiny sign that says Bourbourin. In the distance, you may see a few cars parked together in a makeshift lot. I'm told this is an excellent approach but I have yet to explore it.

Alternatively, head for the village of Murs, and right after the Col de Murs (the pass) there is apparently an access to a different section, but I cannot tell you more because I haven't seen this one either.

There's yet another approach, this time from St Hubert, which takes you for a 3.5km walk along the wall. The local tourist office has a pamphlet of the route you can download (it is in French).

The wall is important historically, of course, but also because it is a good example of the dry wall type of construction seen in these parts, so anchored in tradition that it is now protected as part of France's intangible heritage under UNESCO.

Lessons from the plague

Surprisingly enough, many parallels can be drawn between our own Covid-19 epidemic and the epidemic in Marseille 300 years earlier.

Initially, authorities sought to downplay the epidemic's importance and pass it off as some kind of benign flu or other illness, anything but a contagious epidemic that might scare people and disrupt the economy. By the time the deaths could no longer be hidden, it was too late to stop it in its tracks and it would spread wildly.

The economy would be a driving force behind life and death decisions, then as now. Lives would be put at risk to safeguard fortunes, and business would only grudgingly give way to health. But many deaths would have to occur before that happened.

Radical measures would be taken during both epidemics: permits, fines (or in the 1720s, "shoot to kill"), the shutting down of markets, and barriers to movement, whether between regions or simply within the city. In an early lesson, building the wall seems to have worked, at least somewhat. While the epidemic went around the wall to reach Avignon, there is anecdotal evidence that along the wall, villages suffered significantly less and reported far fewer deaths.

The idea that "disease does not discriminate" was proven false then, as it is now. During the 1720 plague, wealthy city residents would leave town (at times disobeying the rules) and head for regions untouched by illness. As the coronavirus spread through France in 2020, Parisians (and to a certain extent residents of other large cities) headed out of the capital to their secondary residences or to relatively untouched regions. Those unable to afford a move would be cloistered in the city, facing the brunt of the epidemic. As was shown during Covid-19, the weakest and most vulnerable populations suffered the most.

Today we have social media that helps amplify fake news and creates scientific doubt in the population. Well, 1720s Marseille was no different: they had public speakers, pamphlets, leaflets and newspapers, and the conspiracy theorists were out in full force then, as they are now.

Along the mur de la peste. (Photo Marianne Casamance, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Along the mur de la peste. (Photo Marianne Casamance, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)It may have been 300 years ago, but the past can still inform the present. Walking along the wall is a solitary journey and chances are you won't run into too many people. You'll have ample time to reflect on history repeating itself, except this time, you won't have an armed soldier pointing a gun at you and threatening to shoot unless you turn back...

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!

Pin these and save for later!