Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Culture & Civilization ›

- Prehistoric Caves

Mysterious Prehistoric Caves: France's Leading Painted Cave Art Sites

Updated 23 March 2024 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

France has hundreds of caves: some are filled with parietal, or prehistoric art – a few are originals, others are replicas. Some caves are man-made, and others are used for storage, or even dwellings. Here are some of the most famous.

It was 1940 and summer was almost over in the Dordogne. The occupying Germans were overrunning France. A mechanic's apprentice, 18-year-old Marcel Ravidat, was walking his dog (or not, depending on the version of this story) when the dog, spotting a rabbit, chased it into a small hole.

Intrigued, Marcel began digging, hoping he had discovered a hidden entrance to an abandoned manor. He threw a stone into the opening and it fell, and fell, and fell.

From left to right: Léon Laval (teacher), Marcel Ravidat and Jacques Marsal (two of the four teenagers who uncovered the grotto), Father Henri Breuil (pre-historian who authenticated the discovery). Photo D.R./archeologie.culture.fr

From left to right: Léon Laval (teacher), Marcel Ravidat and Jacques Marsal (two of the four teenagers who uncovered the grotto), Father Henri Breuil (pre-historian who authenticated the discovery). Photo D.R./archeologie.culture.frA few days later he returned with friends. Armed with a long blade and two home-made lamps, they lowered themselves eight meters into the cave and were met with a stunning sight: walls covered in paintings of galloping horses, aurochs, bisons... a cavernous room that would come to be known as the Cave des Taureaux (Great Hall of the Bulls).

At first, the boys swore to keep their secret but boys being boys, they soon told someone who told someone... and eventually an archaeologist visited the site, so struck by it that he called it the "Sistine Chapel of Prehistory".

And so were the Lascaux Caves, the most famous caves in France, brought from their early days as a refuge for homo sapiens into the modern world.

Map of the best prehistoric caves of France

The include some caves that are World Heritage Sites, as well as some of the oldest, most visited, or best-loved caves in France.

The best caves in France that date from prehistory

Everyone loves a mysterious cave, and we French are no different.

Our prehistoric heritage proves it: we've loved caves for... well, forever, since humans first started seeking shelter in what would someday become La France. And let's be honest: France has some of the best caves in the world.

Caves are dark and secretive; they protect us against the elements, or would have, long ago. They once hid us from human predators whose sense of smell wasn't developed enough to sniff us out. And in summer, they kept us cool well before fans and air conditioning were invented.

Prehistoric caves take us into the dusty corners of our history. They are often places where our secrets have gone to die, only to be resurrected when someone stumbles into one or a curious explorer comes to visit.

The Lascaux cave paintings may be the most famous prehistoric cave paintings in France, or even in the world (at least that's what we are told as children in school, as we begin our arduous climb through centuries of history).

And what secrets might be hidden in Lascaux?

The best caves in the Dordogne

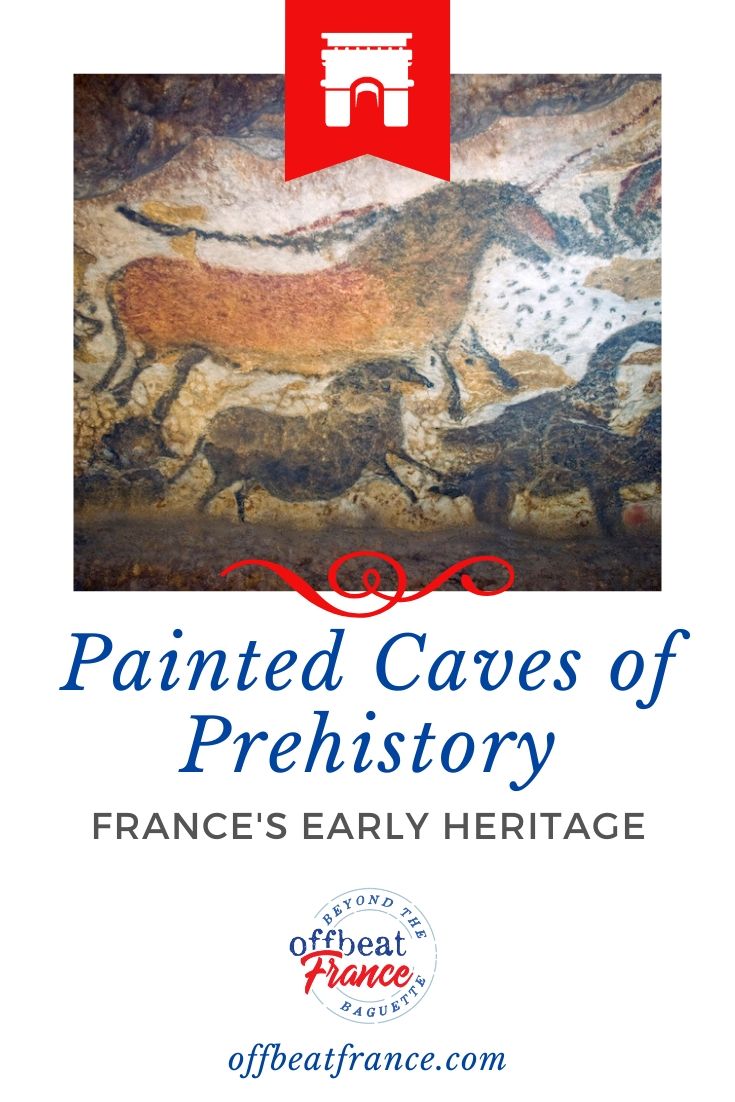

Some of the best caves of France are in the Dordogne in southwestern France, and Lascaux in the Vézère Valley is probably at the top of the list when it comes to painted caves in France: its decorated cave walls were were probably the work of Magdalenians of the Upper Paleolithic somewhere between 17,000 and 20,000 years, but let's not quibble over a few millennia.

Decorated Caves of Lascaux, France

Imagine you are a prehistoric cave dweller during the Ice Age, leaving your shelter to hunt for food when the weather becomes clement.

As you look out on the hilly, even jagged landscape, you see horses galloping in the distance, some perhaps slipping on remnants of ice, or galloping away firmly if this happens to be one of the warmer periods of melt.

Bison and aurochs are plentiful, although you will mostly be hunting sheep and fish, much easier to catch.

Yet when you return to your cave, you won't be painting those mundane sheep and fish, as might be expected — you'll be etching a series of aspirational creatures, those bison and aurochs you see in the distance but don't approach.

an There isn't a fish or sheep in sight on the walls of Lascaux... Don't you find that strange?

And what about the so-called Unicorn? It's the first thing you see when you enter Lascaux, an unidentifiable creature with two thin straight horns pointing forward. Look closely and you'll see it is a mixture of styles... a round stomach, a square head...

Is it a man covered in animal skins? A composite of different animals? An artist's mistake? What IS this unicorn?

Who knows... and the secret remains.

France cave paintings - replicas in Lascaux II. Photo by Jack Versloot / CC BY

France cave paintings - replicas in Lascaux II. Photo by Jack Versloot / CC BYThe paintings cover the walls and ceilings deep into the cave, so smooth you almost feel like running your hands over them. And like all things famous, they beg comparison: some historians call it the Sistine Chapel of cave art, and others, well, the first ever gallery of street art... perhaps, in a way.

Visiting Lascaux caves

Lascaux was only opened to visitors from 1948 to 1963. The caves then closed, their paintings damaged by sunlight and carbon dioxide (breathed out by the 1200 daily visitors), crystals and fungus — human visitors damaged them more in a few years than in the millennia they had remained hidden.

Lascaux may be closed, but that doesn't mean we cannot see the cave paintings.

Let me explain.

These days, there are FOUR Lascaux caves.

Lascaux I is the original complex, and 200m away is Lascaux II, an exact copy – or at least the copy of the Great Hall of the Bulls and the Painted Gallery. It also happens to be the most visited painted cave in the world, and the first cave replica of its kind. There's plenty to see, because it reproduces 90% of the best paintings and engravings of the main Lascaux caves.

Lascaux III, built in 2012, is a set of five portable replicas which can be exhibited anywhere in the world.

Lascaux IV is the Big One, the full replica of the principal Lascaux cave, built inside a real cave to retain the dark and dank atmosphere of the original, as well as its echoes.

This is more of a total experience, where 8000m² of cave paintings (some 50 artists spent nearly four years re-creating 1000 images and symbols) meet technology. It is a museum, part of the International Centre for Parietal Art.

If Lascaux is so special, it is because of age, of course, but also because of the rock paintings themselves.

Rather than static and flat, they actually appear to embody movement. The animals seem to be posing rather than standing still: they are hunted, afraid, pursued by men with spears. And you can tell.

They are also huge, often covering an entire wall or ceiling, quite humbling, and evidence that many thousands of years ago, our ancestors were skilled artists with much to communicate. To fully understand what you're seeing and travel back 15,000 into prehistory, take a full-day tour to immerse yourself and truly understand what you're seeing.

Gouffre de Proumeyssac

A 40-minute drive from Lascaux is one of the best caves in Dordogne, which deserves the name it was once known for: the Devil's Hole. In winter, smoke is expelled from the cave and locals once thought hell was burning below. It was also a convenient place to dump the bodies of travellers killed by local highwaymen along a frequented road nearby.

It's also known as the Cathedral of Crystals for the extensive crystallization of its walls and ceiling. It is all revealed gloriously if you choose to be lowered into the cave in a motorized platform which turns on itself, revealing all the wonder, bit by bit.

I've only highlighted these two but the list of French caves can seem rather extensive, even if we just stick to the Dordogne: you can visit the reindeer paintings at the Grotte de Font-de-Gaume, the Abri de Cap Blanc and its woman standing with a horse (she may have been the artist), the gigantic Gouffre de Padirac or the Grotte de Rouffignac and its many woolly mammoth paintings.

Ancient caves in southern France

Don't think the caves are all in the Dordogne though; you'd be wrong, because you'll find plenty of prehistoric caves in southern France — though not in the southern France of Provence and olives and bouillabaisse, but the one with the mountains and grottoes and enormous cavities that threaten to swallow you up into the ground. Many of the more spectacular prehistoric sites are concentrated in the Ardèche in southeastern France and the Ariège in the Pyrenees.

Chauvet Cave and Caverne du Pont d'Arc

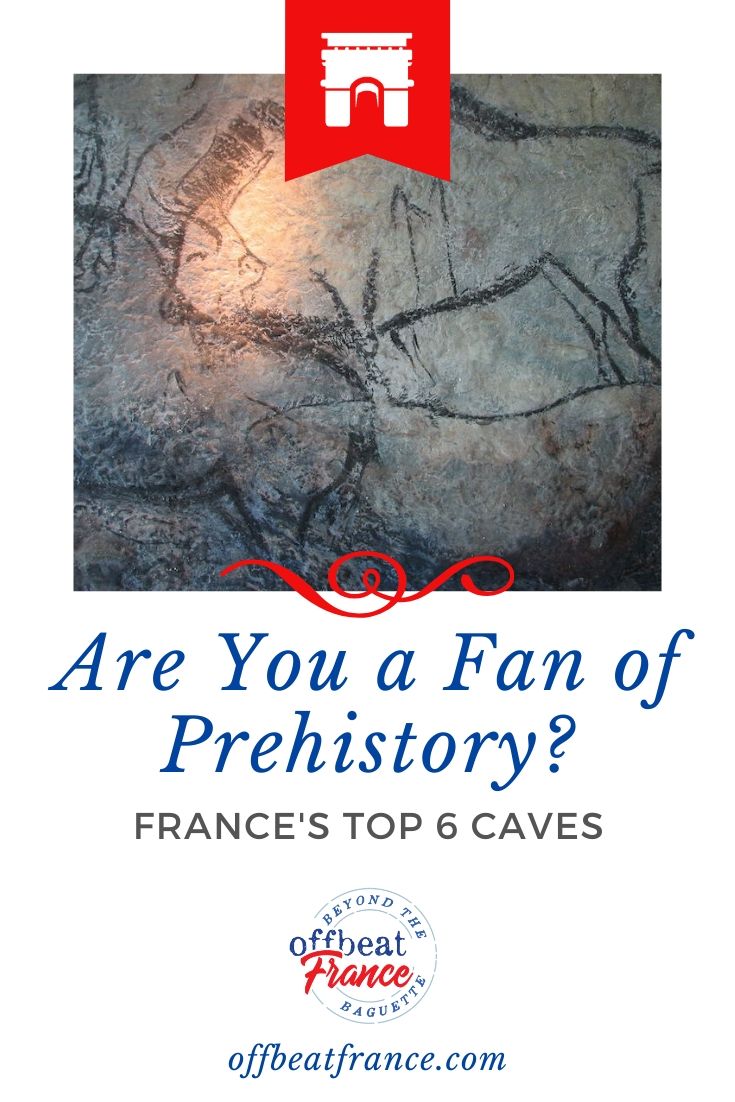

One of the most fascinating ancient caves in France is Chauvet, named after Jean-Marie Chauvet, one of the speleologists who discovered it. For 20,000 years it sat, undisturbed, because a rockfall blocked its access. Now, it is protected as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Yet it is spectacular, or at least its replica is (the world's largest, by the way, ten times the size of Lascaux IV). More than 1000 cave drawings represent 14 different animals including the inescapable woolly mammoth, cave lions and even panthers, all of which are now extinct. Some unusual animals are pictured, like the rhinoceros... I had no idea they roamed Europe way back when.

The artists used charcoal and natural pigments to draw and the prehistoric art is incredibly emotive, with strong expressions. When a group of lions are chasing a herd of bisons, you can instantly see the murderous intention in their eyes and almost feel the movement of their limbs. These are not individual drawings, but frescoes of entire populations interacting with one another.

The replica is housed in a round building where the cave paintings have been reproduced on a scale of 1:1, bringing the entire complex to life. The artwork has been faithfully rendered, as have other details like stalagmites and rock falls. The exception is where there was nothing to reproduce — bare walls, in other words.

You don't feel you're looking at an imitation but at the real thing.

They've also done their best to replicate the atmosphere: you can smell the must, hear the distant reverberations of silence or the echo, and you might even shiver a little (it's not cold, just cool), just as the original inhabitants might have. You will be forgiven if you close your eyes for a moment and imagine you are holding a piece of stone dipped in a natural pigment, ready to paint a bison on the wall more than 30,000 years ago, during the Stone Age.

One more thing: the names of these caves are confusing and often interchangeable.

The original grotto is called Chauvet. The replica, often called Chauvet 2 but officially named the Caverne du Pont d'Arc, is a few kilometers away in the village of Vallon-Pont-d'Arc. The confusion comes from a copyright dispute. Now you know.

Chauvet (the original grotto) may not be one of those prehistoric caves in France open to the public, but by visiting the Caverne Pont d'Arc (the replica) we can at least admire what once was without destroying it.

Find out more about Lascaux here.

The prehistoric rhinos of Chauvet, among the best painted caves of France. (Photo See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The prehistoric rhinos of Chauvet, among the best painted caves of France. (Photo See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)Aven d'Orgnac

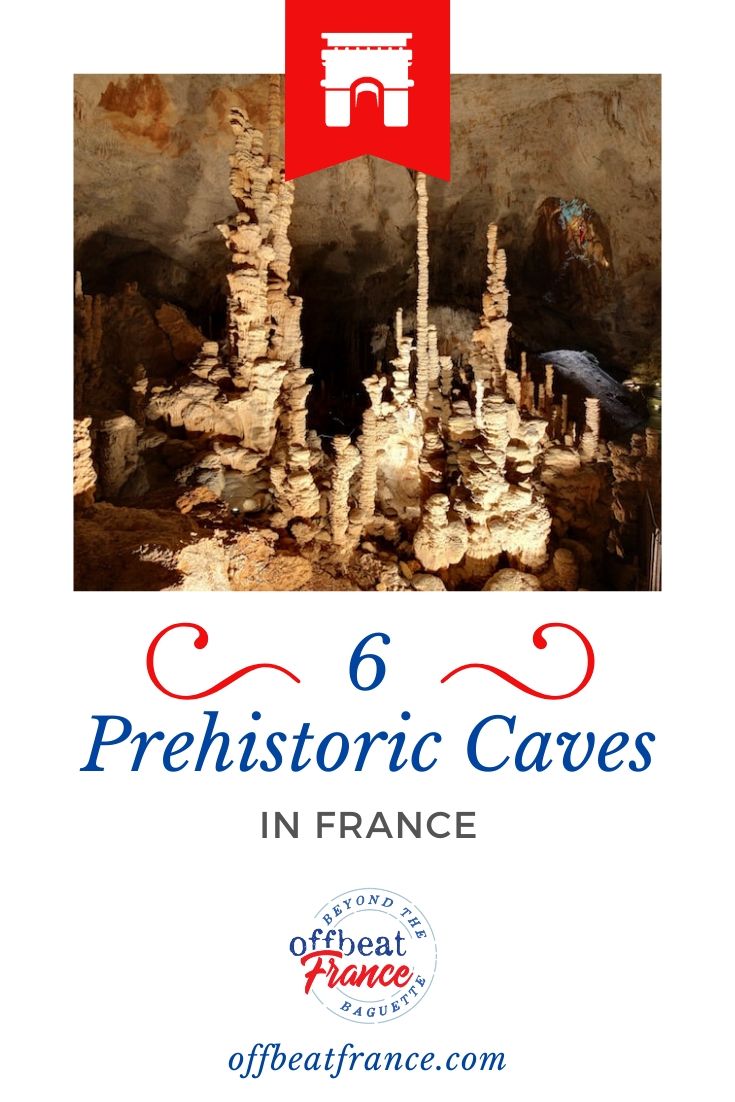

Half an hour from Chauvet is the Aven d'Orgnac, which differs dramatically from its cousin nearby. I remember darting in here on an impossibly hot summer day, jostling against dozens of other visitors who seemingly had the same idea.

But once inside, you'll forget everyone else and feel you've walked into a science fiction movie, surrounded by strange growths that reach high beyond your sight. This is a real live grotto that makes your hair frizz and sends droplets of water your way. This is a grotto you can visit, going deep underground and by the time you've reached the bottom, you'll have descended 700 steps (don't worry, there's a lift to come back up).

The cave was carved by water some six million years ago and contains every shape of formation here: icicles, totems, pine cones, and a lovely room called Chaos. It'll satisfy both your historical cravings and your more mysterious leanings.

Upper chamber of the Aven d'Orgnac, by Benh LIEU SONG - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Upper chamber of the Aven d'Orgnac, by Benh LIEU SONG - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia CommonsIf stalagmites are your thing, the Aven Armand in the Cevennes National Park happens to have the largest one in the world: it's 30m high (as well as another 400 that are pretty spectacular too).

You'll reach it on a funicular that goes down into the earth to a platform that lets you gasp at what you're seeing: you'll feel like you're in a land of fantasy, with unearthly shapes shooting up from every available space, like a forest of stone. The rainbow lights are stunning but provide more of an entertainment vibe than the silence I personally prefer in the face of something so grandiose.

Unexplored for millennia, this was one of those abysses surrounded by terrifying stories and legends about devils' mouths swallowing up herds of animals and stray passers-by.

An "aven", by the way, means a natural opening in the ancient Occitan tongue.

Find out more about Aven d'Orgnac here.

Grotte de Niaux

But back to the cave paintings. What if you want to see real cave paintings rather than replicas?

Then head for the Grotte de Niaux in the Ariège, over in the Pyrenees. This is not just a cave but a complex that stretches 14km underground, with artwork more recent than that of Lascaux: it is only 11,000 to 17,000 years old and belongs to the Magdalenian age, which is the tail end of Europe's Upper Paleolithic.

The Niaux Caves have been accessible since 1869 and the art represents a wide variety of animals — bisons, horses, deer, ibex and yes, even fish (and a weasel)! The painted horses aren't dissimilar to the pottok you can find today in the Basque country...

No one lived here, because no domestic detritus has been found. So why did people venture into the cave? For occasional protection, perhaps, or just to paint, or perhaps, as is believed, for spiritual or ancestral shamanistic rituals. We may never know.

Find out more about the Grotte de Niaux here.

Bisons in Niaux Caves

Bisons in Niaux CavesGrotte du Mas-d’Azil

The Ariège, just as riddled with grottoes as the Dordogne, is also home to the unusual Mas-d'Azil cave, which is just over an hour's drive south from the city of Toulouse.

Why unusual? Because no other French cave is quite like it: a road goes right through it. Not only that, but the opening is gigantic, 51m high and nearly as large across. If you drive by, you can't miss it. A normal road leads to it, and you know you're near when you pass the sign that tells you to turn your headlights on.

Without the road we would have no cave, because it was while excavating for the road that the first prehistoric remnants were found.

This is a cave where people lived, although not at first. Initially the cave was populated by animals — we know this because of the mounds of bones found here that belonged to woolly mammoths and rhinos and cave bears. Afterwards, humans moved in because artefacts have been unearthed, such as spear heads, flat harpoons and painted stones, and even a few pottery shards.

Its cave art dates from more or less the same period as the Niaux Cave and is at least as diverse. For something a bit different, you can explore some of the dozen or so Bronze Age dolmens scattered around the grotto.

But this is a cave that has been adapted for use beyond prehistory. There is evidence of its use as a refuge by a variety of religious groups: persecuted Christians in the 3rd century, then Cathars, and finally Protestants hiding during the religious repressions of the 17th century.

During the war the Nazis wanted to set up aircraft repair shops in the cave but were thwarted by the French claim that traffic would have been too dense. Be grateful for small mercies.

The road into the Mas d'Azil cave by Zunkir — Own Work, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The road into the Mas d'Azil cave by Zunkir — Own Work, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia CommonsThe Ariège is also home to the Cave de la Vache, with plenty of artefacts and decorated objects; the Grotte de Bédeilhac and its clay models, and Lombrives Cave, a behemoth and Europe's largest cave whose seven super-imposed layers, or so says the legend, house the tomb of Hercules' lover... All these caves have seen history unfurl, whether as shelters during the Magdalenian era, sacred sites for the Cathars or hiding places for persecuted Protestants.

Find out more about the Mas d'Azil here.

🚘 Most caves in France are (for obvious reasons) out in the countryside. A very few are reachable by public transport, but the rest require a ride. You can take a tour, like this one to Lascaux from Sarlat, or you can rent a car and roam. Use this link to uncover the lowest car rental prices in France.

Cosquer Mediterranée

This museum isn't your typical collection of artifacts, but a life-sized replica of a Paleolithic cave adorned with our ancestors' artistic creations.

It all started in 1985, when a master diver named Henri Cosquer stumbled upon the entrance to an underwater tunnel while exploring the Calanques national park around Cassis, near Marseille. This passage ultimately led him to a breathtaking cave unlike anything he'd ever seen. Armed only with a light and a cord as a lifeline, Cosquer ventured deeper, becoming the first person in over 20,000 years to witness the drawings adorning the cave walls.

The cave was filled with hundreds of detailed drawings of animals, including horses and even penguins, alongside mysterious handprints.

Sadly, the cave was filling up rapidly, the rising water levels threatening to destroy its priceless history. To preserve them, a meticulous replica was built right off the port in Marseille.

After waiting for an elevator to transport you underground, you'll ride through the cave and slowly make your way past stunning animal drawings and handprints, some of which may be as old 33,000 years. Without this replica, these images would be forever lost.

Find out more about Cosquer Mediterranée here.

The best (man-made) caves of France

Not all our underground spaces are natural.

Many caves in France are man-made, often hewn from stone for some particular purpose (like hiding during war or, often, food related).

Troglodyte Caves in France

I've always loved troglodytes, or any cave dwellers, really. Turkey has done an intriguing job of turning their trogloditic caves into attractions and dwellings and although on a much smaller scale, France too wants to capitalize on its more accessible caves.

Many of these troglodytic caves are scattered around the French countryside and some complexes are truly spectacular.

If you're ever visiting one of the region's fabulous chateaux, or visiting the cities of Tours or Blois, France's best-preserved and most unusual troglodytic complex is in the Loire Valley, in Trôo, about an hour's drive from either city. It is set into a steep hill (lots of walking up and down) like a layered cake, with the oldest medieval structures at the bottom, the troglodytic caves in the middle and the "upper town" above, all of them connected by pathways.

Trôo already existed at the time of the Gauls and many of the openings were dug out as shelters and places to live or to keep farm animals or cattle. Later, they served as homes for poor people who couldn't afford a house and these days, the village is full of artists and environmentalists who see living with (or inside) nature as a life choice. Many may look like normal houses from the outside, although they're actually built into the mountain. Some have been turned into holiday homes so if you've ever wanted to experience living in a (relatively modern) cave, now's your chance!

The caves of France aren't always underground: here, the Village of Trôo. Photo Val de Loire 41

The caves of France aren't always underground: here, the Village of Trôo. Photo Val de Loire 41Another troglodytic complex, this time in the Auvergne, are the limestone Jonas Caves in St. Pierre Colamin, originally dug out by the Celts and then settled by monks in the Middle Ages. They may also have been inhabited by Templars at some point.

At their height, they housed up to 700 people and contained 70 rooms including a castle, a bakery and a chapel, a jail, stables, latrines (and more) over five floors, a rather sophisticated structure that is hard to imagine given that, unlike Trôo, these caves are somewhat bare. The rooms still stand, and some host cave paintings of a different kind: not bison or bears, like their prehistoric counterparts, but medieval religious or daily scenes of life.

Medieval paintings on the walls of the Jonas Caves, France (photo David Lofink via CC 2.0)

Medieval paintings on the walls of the Jonas Caves, France (photo David Lofink via CC 2.0)Ice Grotto at the Mer de Glace, Chamonix

This man-made cave is smack in the middle of the Alps, up the hill from Chamonix. It is carved out of a glacier and even more unusual, it has to be recarved each year because the glacier itself shifts. It has ice sculptures as well as a Gallery of Crystals — and ice furniture that threatens to melt as you're watching.

You can get there via the little cog railway that goes up to Montenvers station and should you choose to, you can walk back down for the perfect day hike.

The ice cave at Chamonix's Mer de Glace (photo by Denise Mayumi via CC 2

The ice cave at Chamonix's Mer de Glace (photo by Denise Mayumi via CC 2Caves related to gastronomy

Most people are interested in ancient cave paintings in France, but not all French caves are dedicated to walking us through prehistory. While they may be old, many of these caves serve a thoroughly modern purpose: to quench our hunger and our thirst. With food and wine at the heart of so many things French, it should come as no surprise that certain caves are dedicated to food and drink.

Mushroom Caves

The Cave des Roches in the Loire Valley is built on a former stone quarry — a famous one that once produced tufa, the white calcium carbonate stone used to build some of the regions most beautiful chateaux. This stone whitens and hardens once in contact with the air and if you've visited Chenonceau or Blois or Chambord and touched their walls, you'll know tufa.

Below the farm lies yet another troglodytic village, Bourré, a truly offbeat creation.

When production of the common Paris mushroom fell during the 1990s, the owners of the Cave des Roches were faced with the prospect of downsizing — or doing something completely different. They chose the more exciting option and, since the mushroom farm was built on a tufa quarry, they commissioned sculptors to develop a replica of a 19th-century village under ground, all carved in tufa.

Everything is designed to look like a real village: building facades, windows and streets, vines crawling up walls, and even a horse poking its head out of a stall. Not only is this smart business, but it also helps keep alive the ancient art of stone carving and shows off the qualities of the local stone. The mushroom farm now specializes in blue foot mushrooms, or pied bleu, and produces 40% of the world's supply. (The two Instagram posts below will give you an idea of what the village looks like.)

Champagne Caves

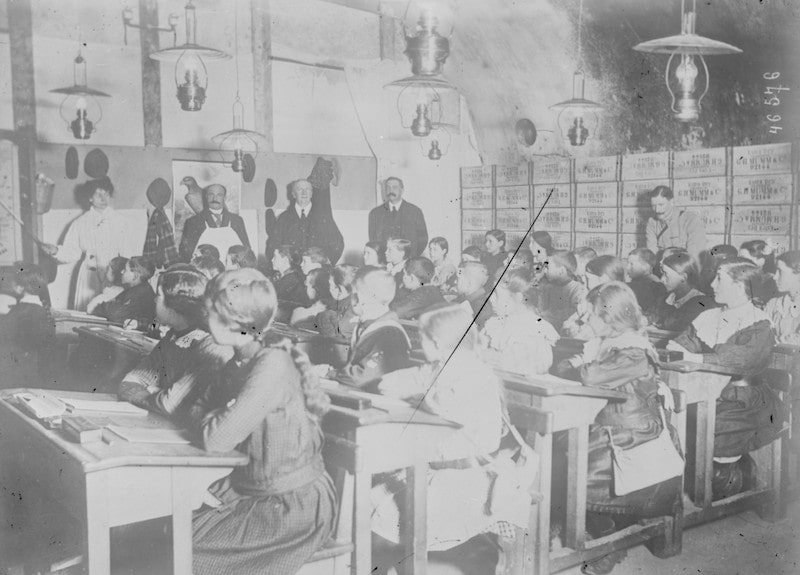

The hill of Saint-Nicaise in Reims is like Swiss cheese, pierced throughout by caves known as crayères, or chalk caves. Miles and miles of tunnels hacked out of the chalk criss-cross the hill's insides, hidden from daylight, with a temperature perfect for storing bottles of champagne...

Many of these tunnels were quarries dating back to Roman times. They provided stones for the building of Reims, including its fabulous cathedral. Eventually, people realized they were perfect for storing wine. Before the era of refrigeration, their constant temperature, humidity and darkness made them... perfect.

During World War I, as German bombs fell over Reims, these champagne caves were the perfect refuges from the war. They served a multitude of tasks; shelter, of course, but also health (hospitals) and education (schools).

Today, with their high ceilings that can reach 30 meters, they are home to millions of bottles of champagne, ageing gracefully. The Caves Ruinart in Reims are a good example of these caves but there are others.

This old newspaper photograph shows how the crayeres were used during World War I - as hospitals, homes and in this case, schools (Source gallica.bnf.fr / BnF)

This old newspaper photograph shows how the crayeres were used during World War I - as hospitals, homes and in this case, schools (Source gallica.bnf.fr / BnF)Roquefort Caves

Cheese caves, you say? Hmmm. Pungent.

But then, Roquefort is one of France's favourite cheeses, a sheep's milk cheese decorated with rich veins of mould (for many, including me, an acquired taste).

Cheese has been made in caves for more than a thousand years and like everything in France that goes back in time, there's a legend attached to Roquefort. One has to do with a young boy who discovered mouldy cheese in a cave and presto, blue-veined cheese was born. According to another, a sleeping boy woke up to see a beautiful woman run by. He had his lunch with him but he left it behind to chase the woman. When he returned a few months later, the cheese had become mouldy. The boy courageously took a bite and again, history was made.

The are plenty of cheese caves, the Roquefort Société being the largest. It is located in the Aveyron, in southern France, yet another area thick with caves.

This is what the Roquefort caves of Aveyron look like (photo Tourisme Aveyron)

This is what the Roquefort caves of Aveyron look like (photo Tourisme Aveyron)More about France's prehistoric caves

If you're fascinated by early rock art, the Bradshaw Foundation is a fountain of information not only about French prehistoric caves but caves from around the world.

Here is a more complete list of cave art you can visit in France by Archaeology Travel.

To book your tickets online for the most popular caves:

- Lascaux

- Chauvet

- Aven d'Orgnac

- Grotte de Niaux

- Grotte du Mas d'Azil

- Ruinart Champagne Caves

- Caves Société Roquefort

Did you enjoy this article? I'd love if you shared it!