Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Culture & Civilization ›

- Renaissance to Republic

Renaissance, Revolution, Republic: France's quest for change

Published 07 November 2023 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

France has an incredibly rich history, as I'm reminded each time I travel around my country, from prehistory to that amazing era of grand monarchs – and the public's reaction to them.

France's history, like most others, I imagine, is filled with quirks and curves that might easily have derailed the present, guiding it onto a different road. The period between the end of the Middle Ages and the modern era is particularly rife with these historical "might-have-beens".

For example, if France hadn't invaded Italy, we might have bypassed the Renaissance and the many châteaux dotting the shores of the Loire River, or if a certain king hadn't converted, France might today be Protestant.

While this period left an indelible cultural mark, we shouldn't forget it was also riddled with strife and class differences, all converging in that one indelible event of our history: the French Revolution.

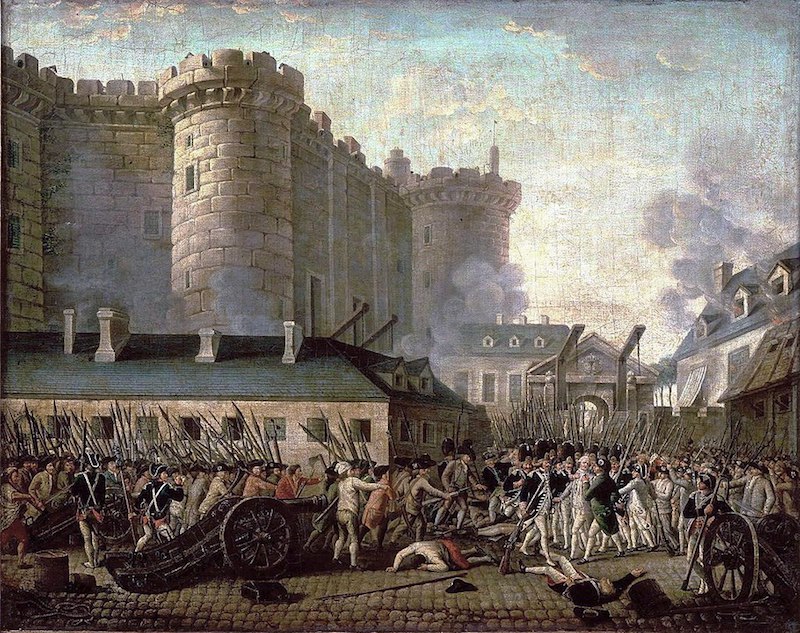

Storming of the Bastille

Storming of the BastilleEven if you're not a fan of history, you'll look at the Arc de Triomphe differently if you know why Napoleon wanted it built, or at the Place de la Concorde if you can imagine the crowds screaming for Louis XVI's head as he approached the guillotine.

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

Renaissance: Rebirth and Brilliance

Renaissance means rebirth, and that’s what France was like in the 15th century, reawakening to classical learning and artistic expression, a sort of cultural rejuvenation.

Italy was already in the throes of the Renaissance when King Charles VIII invaded Italy in 1494. The young King Francis I (François I) was a lover of art and he seized a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Leonardo da Vinci, one of the geniuses of his time, wasn't happy in Florence so when France invited him to France, he jumped at the chance.

Next thing he knew, he was crossing the Alps, with the Mona Lisa tucked under his arm, heading to a new home in the Loire Valley.

This move was a pivotal moment that brought the Renaissance's brightest star into France's cultural orbit. It set the stage for a period of artistic and intellectual fireworks that would light up the French skies for years to come.

Many of the Loire Valley castles we love so much are the product of this time, delicate, beautiful, and ambitious: Amboise and the nearby Clos Lucé, where Leonardo would spend his final years; Chenonceau, possibly our most beloved; Blois and its crazy façades; the enormous Chambord, a marvel of architectural innovation, with its double helix staircase (often attributed to Leonardo despite the lack of evidence); Azay-le-Rideau, which looks as though it is floating on the water; or Villandry, with the most magnificent gardens.

The interior of Chenonceau - with Louis XIV's portrait on the wall on the left

The interior of Chenonceau - with Louis XIV's portrait on the wall on the leftWars of Religion and the Edict of Nantes

Despite the artistic ferment, this was also a time of turmoil, the era of Calvin and Luther, of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, pitting Catholics against Huguenots (as France’s Protestants were known).

The darkest moment of these times may well have been the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre in 1572, when thousands of Huguenots were slaughtered in cold blood under Charles IX in a massacre believed to have been orchestrated by his mother, Catherine de Medici.

Things would only calm down with the accession of King Henry IV to the French throne. He was an unlikely monarch, owing his job to his marriage with Marguerite de Valois, Catherine’s daughter.

But he had a near-fatal flaw: he been brought up Protestant in the Kingdom of Navarre, not a good look in such a Catholic country.

Henry was a pragmatist and converted to Catholicism – he would not have lasted long as king otherwise. He calmed the religious waters for a time by issuing the Edict of Nantes in 1598, granting religious tolerance to the Huguenots. Had he not converted (assuming he managed to hold onto his throne), France might have been… Protestant!

Absolutism and Enlightenment

Possibly France’s most famous royal, Louis XIV the Sun King exemplified the absolute power of the monarchy. Versailles, with its opulent halls and luscious gardens, is the perfect symbol of this unbridled power and the divine right of kings, in which Louis firmly (and conveniently) believed.

Yet all was not well in this fairy-tale land, and the common folk bore the weight of the Sun King's extravagance. The Palace of Versailles may be spectacular, but the people were beginning to grumble about high taxes and famine.

Artists and philosophers like Voltaire and Rousseau became spokesmen for the people, sparking the Enlightenment and challenging the status quo, advocating for liberty, equality, and fraternity. Their ideas percolated through salons and coffee houses, stirring the minds of the French towards revolution.

Yes, times might be bad for many, but there slowly crept in a feeling that things could be changed.

Before their arrest by revolutionaries, the royal family tried to flee to Belgium... here, they prepare for the trip. The escape failed

Before their arrest by revolutionaries, the royal family tried to flee to Belgium... here, they prepare for the trip. The escape failedRebellion and Revolution

On 14 July 1789, the people of Paris seized the Bastille.

The prison's fall was more than a battle; it was a symbol of tyranny's end and the people's uprising. The French Revolution would sweep away the old order, replacing it with a new age where the citizen was sovereign.

Or so it seemed at first.

Radical factions within the Revolution maintained the upper hand for a time, and anywhere between 17,000-40,000 nobles (including King Louis XVI and his wife, Marie-Antoinette) and commoners lost their heads to the guillotine – hence the phrase, "heads will roll". That's what happens to a head after meeting with the guillotine...

When you walk around Paris today, you can easily retrace the steps along which the revolutionaries marched, from City Hall (the Revolution’s headquarters) to the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, himself a product of the revolution.

Historical museums

France is filled with museums and monuments recalling the high points of our history. Here are a few I've visited:

- Chateau Bussy Rabutin And The Salacious Story Of The Count Who Lived There

- Voltaire In Love: The Improbable Power Couple Of The Chateau De Cirey

- The Quirkiest Dijon Museum: A Peek At 19th-Century Burgundian Life

And a peek at other intriguing museums here and there:

Before you go...

If you'd like to further explore France's history, have a browse through my books about France list, which includes many about our past.