Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Destinations ›

- Southern France ›

- Roussillon

Roussillon, Luberon, And The Magic Of Ochre

Published 15 November 2024 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

The village of Roussillon, in the Luberon region of Provence, is unlike most others in the area: its predominant color is ochre, from the buildings to the hills that surround it. Once a world-class ochre mining center, today tourists have replaced miners.

Entering the village of Roussillon is a bit like walking into a painting of gold: gold on the buildings, the dust, and even the hills that cut into the village.

In Roussillon, even the earth blushes. Walk its streets, and you’ll find yourself surrounded by hues you didn’t know existed: vibrant reds, burnt oranges and soft yellows, as though the village were setting itself on fire.

Earthy and fiery, these colors once made Roussillon the capital of ochre, where the valuable pigment was mined and produced and shipped to cities around the world.

Not much ochre production is left, but its remains are visible everywhere.

NOTE: Pages on this site may contain affiliate links, which support this site. See full Privacy Policy here.

Roussillon, in the Luberon region of Provence, is listed as one of France’s most beautiful villages.

Not only is this one of the region’s stunning hilltop hamlets, but it also happens to be visually unique, its ochre color ranging from deep terracotta to soft honey yellows, its very buildings wearing the colors of the earth.

Roussillon’s ochre magic

Legend has it that the rocks of Roussillon gained their vivid color after a tragic love story. A local tale says Lady Sermonde, a young woman betrayed by her lover, threw herself off the village cliffs, her blood staining the earth – and so Roussillon acquired its famous red hues.

But reality may be just a little more mundane.

Ochre was deposited here millions of years ago, turning Roussillon into a natural treasure chest of pigments.

In the late 18th century, Jean-Etienne Astier of nearby Roussillon pioneered its extraction: he developed a method to refine ochre sands into bright pigments, sparking demand across Europe for their use in art, construction and textiles. Ochre mining became central to the local economy, with networks of galleries and quarries supporting an entire community of miners, known as ocriers.

Roussillon would become known as one of the world’s great ochre deposits, its golden tones contrasting with the greenness of the pine forests and the deep blue of the Provençal sky.

It should therefore come as no surprise that the village would be a magnet to artists – like Jean Cocteau and Bernard Buffet – who would want to capture its dazzling brightness.

By the early 20th century, though, synthetic pigments began to replace natural ochre, and the industry waned and today, the fragile ochre hills are preserved as natural sites rather than mined for commerce.

Ochre hasn’t disappeared − you’ll still find it on the landscape, of course, but also in artisanal workshops and today, while the mines no longer operate on an industrial scale, Roussillon’s ochre legacy lives on in its landscape, its artisanal workshops, and on the walls of its homes.

Top things to do in Roussillon for ochre lovers

If you’re hot on the trail of ochre in Roussillon, you won’t have any trouble finding it.

You could just walk around the narrow village streets and admire the ochre-colored walls… learn about ochre production at the museum… or you could head for the hills.

Walk the Ochre Trail (Le Sentier des Ocres)

I admit this is one of the highlights of Roussillon, and I’ve walked it several times.

It is not long − there’s a 30-minute trail and another that lasts about 1.5 hours. It’s well marked, often covered in wood planks, and easy to walk, with steps and handrails to guide you. Cliffs of ochre are brittle, which is why people aren’t allowed to walk on directly on the ground.

Throughout the trail, you’ll witness cliffs of the deepest ochre, so bright you might be tempted to shield your eyes, mesmerizing mounds of gold and dramatic sweeps of reds, oranges, and yellows.

Just don’t wear white − it won’t stay that way for long.

Explore Mines de Bruoux

The mines are in Gargas, a ten-minute drive from Roussillon, and arriving is the beginning of an experience. Several huge openings 15-18m high (50-60 ft) adorn the cliff face, and we are handed hairnets and blue hard hats. It is a mine, after all, and there’s no telling what bits might fall from above. The one disappointment is a ban on photography indoors, so I can only show you the exterior.

Like entering a cathedral whose walls had been smoothed by years of chipping away, the mines give off a pharaonic feel, soaring ceilings on which you can still see the dents left by hand-held chisels. As miners dug their way through the tunnels with pickaxes, the ochre was placed in horse-drawn wagons, which pulled the mineral out of the mine.

The guide traces the history of ochre from the Paleolithic to its 18th-century heyday, and makes the tour interactive, although everything is in French with no translation.

You’ll learn all about how ochre mining has existed since the Paleolithic but only began being exploited in large quantities here in the late 18th century, first in Roussillon, and then here, in Gargas. And how it all went away. Eventually, the mine became a mushroom farm… and now, it’s a showcase.

We are warned to stick together. The tunnels cover 40km (25mi) and should you stray, you might not find your way back. Ever.

Ôkhra - Écomusée de l'ocre

Having seen the raw material, you might now be curious about how it’s processed.

Located on the site of the ochre manufacturing plant, the partly outdoor Okhra Museum explains all that (in French, although there are explanatory panels in English), and plenty more.

You’ll learn that ochre was used in rubber, which for the longest time was orange (ochre veers towards red with heat); the seals on jam jars are the original color, once natural, now cultural. It was also used in linoleum, tires, tiles, lipstick, makeup, the yellow paper used to wrap Gitanes cigarettes…

The industry was powerful, with up to 1000 staff in the region − pretty much every family had someone involved in making ochre. At its height, 44,000 tons of ochre were produced here and shipped from Marseille to ports worldwide, compared with the 800 tons produced today.

You can channel your inner Van Gogh or Matisse, both of whom dabbled in these pigments, and be horrified to find out that when painters licked the tips of their brushes, they were slowly poisoned − the pigments were toxic, and many workers died young from working it.

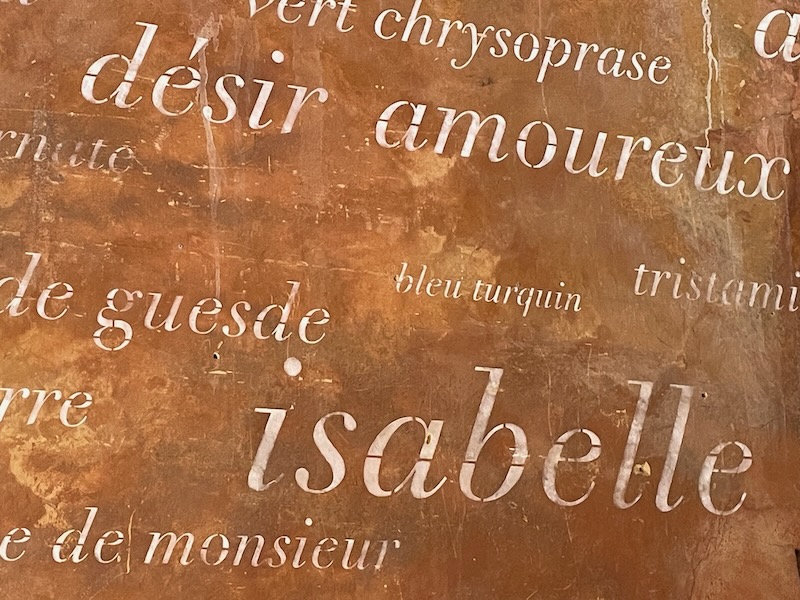

A particularly fascinating room carries the names of original colors on the walls, colors used in the 17th-18th centuries but no longer, labeled sable de rubie (ruby sand), baise moi ma mignonne (kiss me my pretty), cheveux de la reine (queen’s hair), gris merde d’oye (goose dropping gray), desir amoureux (love desire), selle a dos (back saddle), gris poussiere (dust gray), brun vigne (vine brown), and plenty of others too colorful for this story.

Ochre-rich rock is quarried and washed to separate the pigment from the clay. Ochre is prepared by cooking for 24-36 hours (workers slept on the premises to feed furnaces with wood at night) and once dry, it is ground into a fine powder, ready for use in everything from paint to plaster.

Ochre was Provençal gold, so valuable that it was often treated like the precious metal, with pigment recipes passed down the generations.

Walk the streets of the village

The one inevitable encounter with ochre in Roussillon will be by walking its streets. Local ochre has long been used in building materials to protect homes from the intensity of Provence’s sun, and building regulations in town ensure the color scheme is maintained. You’d never get permission to paint your house purple!

Roussillon is built on a hill, and part of its pleasure is to explore the many different levels of the village, from the lower center to the hilly streets, perched plazas and towering fortress, which opens up onto a spectacular view of the Luberon.

A bit of Roussillon history

Roussillon can trace its origins back to the late 10th century, when a small castle was established on a raised earth mound and the area was recorded as "de Rossillione" in 989.

By the 12th century, the church of Sainte-Croix, reporting to the abbey of Saint-André de Villeneuve-lès-Avignon, stood in the village, generating income for the abbey. Throughout the Middle Ages, the fiefdom would change hands among powerful local families, its major claim to fame being the hosting of King Charles IX during his royal tour of France in the mid-16th century.

It wouldn’t become famous for its ochre until the 18th century, its ochre-rich soil turning into a booming industry due to the rising demand for pigments in textile and iron industries. By the 1980s, tourism emerged as Roussillon’s new economic lifeblood, drawing visitors to admire the striking ochre cliffs and explore the preserved remnants of its once-thriving ochre industry.

Where to stay in Roussillon

While visiting Roussillon itself is worthwhile, it also happens to be an excellent base for further exploration of the Luberon: it is about a 15-minute drive to such beloved villages as Bonnieux, Gordes or Lacoste.

Here are some suggestions for accommodations in Roussillon:

- Omma, with beautiful views and an excellent restaurant

- Villa Les Gourdeaux, privately owned if you’re a group and want to rent a house

- Le Clos du Buis, my perennial favorite, a 15-minute drive away

Before you go…

Throughout the Luberon, there’s plenty to keep you busy, from art galleries to sweeping vistas to delightful medieval villages.

If you'd like to go a bit beyond and explore the neighborhood, here are some places I think you’ll enjoy:

- A 25-minute drive will take you to Rustrel, to a place known as the Colorado Provençal, another former ochre quarry.

- L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, a world-renowned antiques center, especially on Sunday mornings (30 min drive)

- Saint-Remy-de-Provence, where van Gogh spent a year in a mental hospital and where you’ll find the magnificent Roman ruins at Glanum (50 min)

- And Avignon, a larger town with plenty of history, and the famous bridge that bears its name (also 50 min)

If you’re curious about life in Roussillon as it once was, Village in the Vaucluse by Harvard professor Laurence Wylie will take you behind closed doors the village of Peyrane, as it’s called in the book – long before Peter Mayle made the region famous.