Unsure about your French table manners? Click Here to download > > How to avoid these 10 food etiquette mistakes !

- Home ›

- Ze French ›

- La Gastronomie ›

- What is Dijon mustard?

How the City of Dijon Lost its Mustard

Published 02 January 2024 by Leyla Alyanak — Parisian by birth, Lyonnaise by adoption, historian by passion

With a name like Dijon mustard, you probably know where it’s from.

Dijon, right?

Not exactly. Your Dijon mustard might well be from Dijon. But it might also be from Japan, Canada or Poland. Or anywhere else.

It’s a sad truth that this venerable condiment may not be what it seems.

What is Dijon mustard, exactly?

Mustard was first cultivated in Dijon in Roman times and turned into a paste to be used with food or for healing. You could find the plants throughout Roman Gaul, alternating with vines and providing them with much-needed nutrients. Wherever wine was grown, so was mustard.

Rome eventually fell but the mustard tradition continued, maintained by monks with a bit of culinary know-how.

During the late Middle Ages, the little seed and the paste it yielded was championed by the Dukes of Burgundy, whose capital was Dijon. They welcomed it to their table, heightening its prestige and turning something into a luxury product.

Once the Palace of the Dukes of Burgundy in Dijon

Once the Palace of the Dukes of Burgundy in DijonIn fact, one legend attributes the naming of mustard to the Dukes’ motto, “Moult me tarde”, which roughly translated means, “I can’t wait”. The more accepted version is a bit different: mustard may have come from “mustrum”, the must mixed with the seeds, and “ardens”, or burning…

Either way, the emergence of mustard guilds would guarantee its survival, and mustard would find its way into other foodstuffs, such as bread.

Initially mixed with wine or must, the tiny brown grains were eventually combined with vinegar – except in Dijon. Here, mustard seeds would be mixed with verjus, or pressed juice from unripe grapes. This made it creamier, less acid, and gave the city’s product a spicy edge over its competitors.

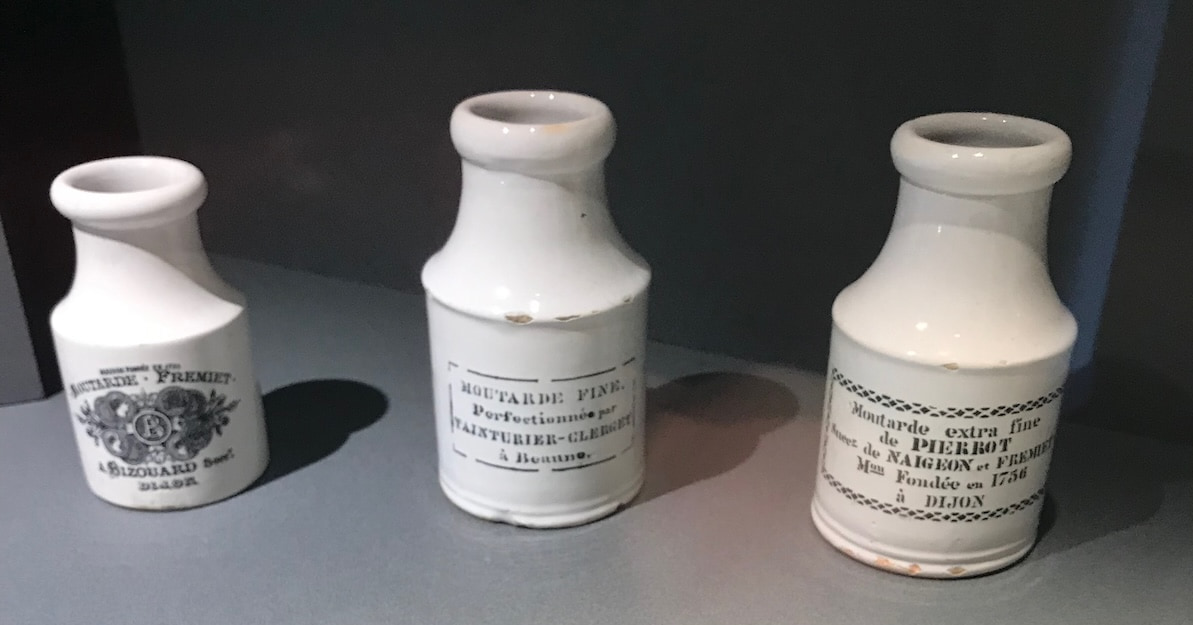

Antique containers found in Dijon's Museum of Burgundian Life - the one on the right is an original Dijon mustard pot. ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFrance

Antique containers found in Dijon's Museum of Burgundian Life - the one on the right is an original Dijon mustard pot. ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFranceBy the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution and steam engine shifted mustard production from artisanal to industrial. This gave birth to all the big brands, such as Grey Poupon, supplier to Emperor Napoleon III, and Maille and Fallot.

This growth would continue until World War II, when mustard farming declined, fields dried up, farmers turned to more lucrative crops, and supplies moved elsewhere, mostly to Canada. Soon, very little mustard was being produced around Dijon.

Dijon mustard: A taste of heaven

Those who have tasted Dijon mustard can recognize it with their eyes closed. In fact, their eyes might be watering and their nostrils clearing if the dose isn’t just right. It’s strong and wicked and will leave you anything but indifferent.

The only thing it has in common with the canary yellow paste that passes as mustard in some countries is the name.

And that is part of its problem.

Unlike champagne or certain wines and cheeses, the name “Dijon mustard” is not protected by law. Probably no one thought to do it at the time, and now it is too late.

Dijon mustard has become a generic name, up for grabs by anyone. You can produce mustard halfway across the world from France and still call it Dijon mustard if you’d like.

It’s more like a recipe: the name refers to the type of mustard (made with brown rather than white seeds), not how it’s made or where it’s from.

Maille's Dijon shop, at 32 Rue de la Liberté, has been selling authentic Dijon mustard here since 1845 ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFrance

Maille's Dijon shop, at 32 Rue de la Liberté, has been selling authentic Dijon mustard here since 1845 ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFranceSeveral unsuccessful efforts were made to revive Dijon’s mustard industry until a clever approach turned things around: mustard from Dijon (and surroundings) was rechristened Moutarde de Bourgogne, or Burgundy Mustard, and in 2009, it received a coveted “geographically protected” label.

Now, any mustard with the "Moutarde de Bourgogne" IGP (Protected Geographical Indication) label must be manufactured in one of these four departments: Côte-d'Or (21), Nièvre (58), Saône-et-Loire (71) or Yonne (89). The mustard seeds must be grown in Burgundy, and made with white AOC Burgundy wine rather than vinegar.

Nor does the Mustard Association of Burgundy fear for its survival. Today, some 600 farmers produce 10,000 tons of mustard seeds a year in Burgundy, quite the success story.

Mustard field in the fall Image by Gundula Vogel from Pixabay

Mustard field in the fall Image by Gundula Vogel from PixabayHow Dijon lost its mustard

So you’d think Dijon mustard would be plentiful in France.

But no, not always.

A few years ago, French shoppers (myself included) were shocked to find our mustard shelves – empty!

Quick to profit from a situation, some individuals sold off their pantry stock, one jar at a time, often at astronomical prices.

For months, we would gather in front of empty shelves, wondering when the magical paste would reappear. Supermarkets tried to fill the gap with some so-called Dijon mustard imported from other parts of the world, but it just didn’t… cut the mustard. Only those desperate enough bought them. The rest of us waited anxiously.

We wanted our Dijon! Or at least our Burgundy mustard…

Supermarkets tried to provide alternatives to Dijon mustard from other countries, but we simply weren't having it ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFrance

Supermarkets tried to provide alternatives to Dijon mustard from other countries, but we simply weren't having it ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFranceWhat had gone wrong?

First, Russia invaded Ukraine, a major producer of white mustard seeds (as opposed to the brown seeds used for Dijon mustard). No longer able to import their seeds from Ukraine, manufacturers of weaker or "yellow" mustards turned to brown seeds, decimating the supply required for Dijon mustard.

Despite a healthy mustard production in Burgundy, most mustard seeds are still imported from Canada, where bad weather hurt the harvest, causing a serious shortage.

The combination of Russia's invasion and Canada's bad weather squeezed the supply of brown mustard seeds. For Burgundy, that meant no mustard.

Driving to Dijon during the Great Mustard Shortage, I noticed a carefully curated window in my hotel lobby, filled with neat rows of the elusive yellow gold. The window was securely locked.

Dijon mustard: a revival

As I walked through the streets of Dijon, I saw plenty of mustard advertised.

Fallot, the oldest firm, has a workshop next to its store, helping demystify the mustard-making process. So does Maille, located in the former Grey-Poupon headquarters in the city’s center. These are small outlets – the major plants are out of town, but well within the boundaries mandated by the IGP.

Have a look at how it's done, or better yet, do what I did and sign up for a mustard-making workshop with the Dijon Tourist Office. It's in French, but so simple you'll have no trouble following along. My group had several non-French speakers and with a bit of hand waving, everyone was taken care of.

Making my own mustard in Dijon ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFrance

Making my own mustard in Dijon ©Leyla Alyanak/OffbeatFranceToday’s Dijon mustard may be generic, and might even be manufactured abroad.

But if you want the real thing, head for the IGP Burgundy Mustard and make sure yours is labelled "Moutarde de Bourgogne".

It is every bit the original, except for the name.